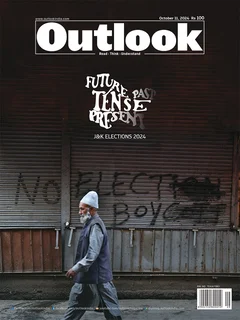

This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Future Tense' issue, dated October 11, 2024. To read more stories from the Issue, click here .

Jamaat-E-Islami, the politico-religious outfit in Kashmir accused of harbouring separatists and resorting to violence, was banned in 2019 for five years, soon after the Pulwama terror attack where more than 40 paramilitary men were killed. The ban was extended for another five years in February this year.

In a strongly worded post on the social media platform X, Home Minister Amit Shah said that the extension of the ban was a part of Prime Minister Modi’s policy of “zero tolerance against terrorism and separatism.” There was buzz the ban would be lifted before the J& K elections, but it remained.

Yet many Jamaat leaders are in the fray in the ongoing elections, fighting as independent candidates. The mainstream political leaders have welcomed Jamaat’s participation in the polls, though former Chief Minister Omar Abdullah didn’t hesitate from taking a jibe at the banned party.

“Well, we were told that the elections were haram (forbidden), but now we are told they are halal (permissible),” says Abdullah. “Anyway, better late than never,” he adds.

Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) President and former Chief Minister Mehbooba was quick to respond to Abdullah’s remarks. “In 1987, the NC and the Congress started an era of halal and haram elections,” said Mehbooba. “The Jamaat-e-Islami was the only opposition back then when the NC and the Congress joined hands.” The PDP president didn’t even spare the NC founder and Abdullah’s grandfather, Sheikh Abdullah. “When Sheikh Abdullah was removed in 1953, elections became haram for 22 years,” retorted Mehbooba.

Mufti, seen to be close to the Jamaat leaders and their cause, has been calling for a lifting of the ban.

Mehbooba’s PDP was accused of having a tacit alliance with the Jamaat to nearly sweep South Kashmir in the 2014 elections before forging a coalition with the BJP.

So, where does the Jamaat-e-Islami stand now vis-a-vis the democratic process? Why is the Centre letting its members contest elections—there are at least nine independent candidates openly backed by the Jamaat—when it hasn’t lifted the ban?

“When the parliamentary elections were announced, we got a message from New Delhi through the agencies that we should field indirect candidates,” says Ghulam Qadir Wani who heads the Jamaat-e-Islami’s panel to decide on election. “We expressed our strong desire to participate in the elections, but we said we would rather field our candidates directly under the party banner if the ban was lifted,” says Wani. He says that the Jamaat leadership was told that New Delhi was considering to lift the ban. Jamaat members voted in the Lok Sabha elections earlier in June, as a show of their belief in the democratic process and to convince the Centre to lift the ban on them in the assembly elections. But it didn’t happen.

Many Jamaat leaders are in the fray in the ongoing elections, fighting as independent candidates. The mainstream political leaders have welcomed Jamaat’s participation in the polls.

The relationship between the Jamaat and the country’s central leadership has always been fraught. The BJP came down heavily on them in 2019 as it saw the Jamaat as a potential challenge to its “Naya Kashmir” project. Jamaat’s assets worth over a hundred crore rupees were seized, with bank accounts frozen and schools, seminaries and other institutions rendered defunct as well. A widespread crackdown was launched against the Jamaat and its top leadership and many middle-rung and lower-ranked officials and activists were put behind bars.

And yet, before the assembly elections were announced, there was speculation that the Jamaat had reached an understanding with the Centre. As an indication of this, some of the jailed leaders of the party, like Faheem Ramzan and Moin-ul-Islam, were released from prison. But other prominent leaders like its former president, Hameed Fayaz and the party spokesman and the head of the political wing Zahid Ali are still in jail.

But the talks soon broke down as Centre didn’t lift the ban. “We were so eagerly looking forward to the revocation of the ban and direct participation in the ongoing elections,” says Mohammad Yusuf Rather, who was the party’s district president in Kulgam. Despite the dialogue running into rough weather, the Jamaat leadership decided to participate in the assembly elections indirectly.

“Reaffirming our belief in the democratic system, we decided to field, against all odds, a few independent candidates besides backing a few more,” says Wani. In the first phase of elections, the Jamaat-e-Islami formed a loose alliance with Engineer Rashid’s Awami Ittehad Party (AIP) with an understanding that the two parties would back each other’s candidates wherever there was a need.

Despite the ban and limited resources, the Jamaat and its followers are being viewed very seriously even if the final tally of the seats, which some Jamaat leaders say will be between three to five, may not make any significant difference to the government formation. A top intelligence officer, who keeps a close watch on Kashmir politics, puts the number of seats at two. “I think they may win the Kulgam seat,” he says. In Kulgam, Sayyar Ahmad Reshi is fighting against the four-time MLA of CPI (M), Mohammad Yousuf Tarigami.

The relationship between the Jamaat and the country’s central leadership has always been fraught. The BJP came down heavily on them in 2019 as it saw the Jamaat as a potential challenge to its “Naya Kashmir” project.

A senior police officer, who has been at the forefront of the counterinsurgency operations, says the Jamaat may have contributed to education and philanthropy in Kashmir, but they cannot be absolved of the nearly hundred thousand deaths that occurred because of insurgency since the 1990s. “What did they give Kashmir after sending nearly a hundred thousand people to graveyards?” he asks. “The kind of statements they issue now and the kind of commitment they express for democracy should have come earlier. Given their widespread outreach among masses because of their work in the field of education and social work, they could have made a huge difference.”

The Jamaat, however, has all along been forcefully rejecting such accusations. “It’s unfortunate that some people hurl such wild accusations at us without trying to understand how and why it all transpired. We are more sinned against than sinning,” says Wani. When the armed uprising began to sprout in 1988-89, the Jamaat was just another politico-religious party that had nothing to do with militancy, and this distance from the gun was maintained for another two to three years.

When some Jamaat leaders felt that the need of the hour was to have an armed wing as other political or religious parties also backed some militant organisations as their armed wings, it led to heated debates and major disagreements among Jamaat’s top ranks. Especially the leadership from South Kashmir was totally opposed to associating the party with any militant organisation. It was the leadership from North led by Syed Ali Shah Geelani and some of his close associates that backed this idea that, despite serious opposition from within prevailed.

“It was the Jamaat-e-Islami leadership from north Kashmir, especially Geelani sahab, that not only floated this idea but prevailed,” says Rather. And that is how the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen was associated with the Jamaat-e-Islami’s rank and file, not only recruiting for the militant outfit but also holding many political positions as the party’s political mentor. The Jamaat in essence became Hizb-ul-mujahideen’s political bureau of sort. It had a primary role in policymaking. The Hizb thus became fully subservient to its political godfathers – the Jamaat leadership.

Jammat leaders say pressure kept mounting on them, not just from within the party ranks but also from the people who were so driven to desperation by the local politics and central leadership in New Delhi that they unconditionally supported militancy. “Who in Kashmir didn’t support the gun back in the day?” asks Rather.

In the late 90s, the Jamaat officially distanced itself from the gun. The then Amir-e-Jamaat Ghulam Muhammad Bhat made an announcement that Jamaat had dissociated itself from all underground and militant activities and would remain, as it always was, a politico-religious party with its cadre committed to the social service that the party had been doing since its inception. The decision, however, might have come a little too late as the Jamaat cadres and their families suffered massive casualties, particularly at the hands of the government-backed militia Ikhwan-ul-Muslimeen.

“We suffered hugely at the hands of the Ikhwanis,” recalls Rather. In many cases, neighbours from our own villages joined the pro-government militia before they were unleashed on us, and we were subjected to gruesome torture, harassment and every inhuman treatment that could be given to us,” he says.

Those few years shook the Jamaat to its core, even threatening its existence which prompted it to renounce militancy and get back to its socio-religious work, with a focus on education. Education has always remained the key area of the party and that is why every sector from the police to bureaucracy to judiciary has a fair share of employees who have done their basic education from schools run by the Jamaat across Kashmir.

That is why almost all the Jamaat-e-Islami affiliated politicians, too, have a solid educational background. Despite ban, arrests and other hardships, the tradition continues even now. Five of the former Jamaat members who are contesting the ongoing assembly elections have multiple degrees and qualifications in different fields.

The assembly election results will be another turning point in the Jamaat’s history. If the independent candidates backed by the Jamaat do make a political dent and can be kingmakers in case of a close verdict, it may signal its return to democratic politics in a more active way.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(Shabir Hussain is a senior journalist)

(This appeared in the print as 'A Strategic Comeback')