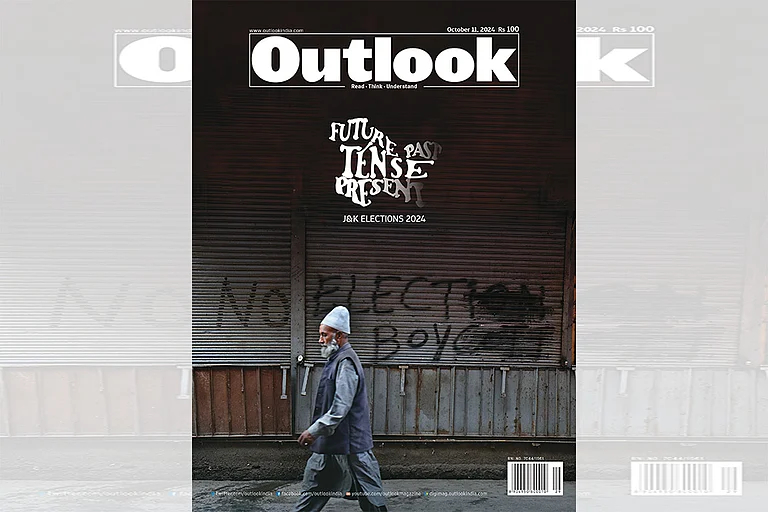

This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Future Tense' issue, dated October 11, 2024. To read more stories from the Issue, click here.

This is the first assembly election in Jammu and Kashmir since the region was designated a Union Territory under the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act 2019, passed on 9 August, 2019. Once an autonomous state within the Indian Union, J&K had extensive powers, including its own prime minister and Sadr-e-Riyasat until 1965, when these positions were replaced by that of the chief minister and governor.

Ahead of the announcement of the election in July 2024, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) expanded the administrative powers of the Lieutenant Governor (LG) significantly.

The move made former Chief Minister and National Conference (NC) vice-president Omar Abdullah angry. “The people of J&K deserve better than a powerless rubber stamp CM who will have to beg the LG to get his/her peon appointed,” Abdullah said. Both Abdullah and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) President Mehbooba Mufti said they would not participate in the election in a Union Territory, but when the election was announced, they had a change of heart. However, the NC vice president soon realised it was a tough fight. He had lost the North Kashmir Baramulla parliamentary seat earlier this year to jailed leader Engineer Rashid. So, an uncertain Abdullah decided to contest from two constituencies this time: Budgam and Ganderbal. Mehbooba Mufti abstained from contesting in the polls herself, but has been campaigning vigorously all across Jammu and Kashmir and also for her daughter, Iltija Mufti, in the Bijbehara constituency.

After the assembly election announcement, the NC and the Congress announced a seat-sharing agreement. However, the negotiations were complicated by Congress’s unusual demand for the Amirakadal seat, which includes Lal Chowk, citing that Rahul Gandhi had ice cream there! The alliance was eventually formed with the allies contesting 83 of the 90 seats: 51 for the NC and 32 for the Congress. The CPI(M) and the Panthers Party received two seats, while the two parties engaged in “friendly contests” for six seats: four in Jammu and two in Kashmir.

Yet, the alliance soon unravelled. NC leaders, who were supposed to support the Congress candidate in designated constituencies, resigned and contested as independents instead. Despite an opportunity to challenge the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Jammu where militancy has surged, the Congress focused more on Kashmir.

Rahul Gandhi extensively campaigned in Kashmir, even at Sopore, once a hotbed of separatism. Many analysts here say it appears that the Congress is hesitant to shoulder the “burden” of Kashmir till it forms the government at the Centre.

Initially, the NC believed it had the momentum on its side. The party forged an alliance with the Congress to dispel concerns that the party might eventually align with the BJP. The NC was acutely aware of the consequences of associating with the BJP, especially after having seen the fallout for the PDP. In the 2014 election, the PDP had formed a short-lived alliance with the BJP. Now, the party is facing accusations of allowing the BJP to gain a significant foothold in J&K for the first time in 70 years.

The pressing question is whether statehood of J&K, its demographics and land will be preserved as they are the focal points of this election.

Within a year after the dissolution of the assembly on August 5, 2019, Article 370 was abrogated, and leaders like Omar Abdullah, Mehbooba Mufti and Farooq Abdullah along with thousands of others were arrested. The BJP claimed it ushered in “Naya Kashmir,” after the abrogation saying that the people are happy, stone-pelting has ceased, and that militancy is a thing of the past. While the party may point to a decrease in overt violence, the reality is more nuanced. As Mehbooba Mufti says, militancy has merely shifted focus, with increased tensions now spilling over into Jammu.

On December 11, 2023 the Supreme Court upheld the abrogation of Article 370, simultaneously directing elections be held. Earlier a delimitation exercise was conducted, which added six new seats for Jammu, but only one for Kashmir. The LG has the authority to nominate five additional members, effectively giving the BJP an initial advantage of five seats, while others begin with none. In Kashmir, the BJP chose to run in only 19. The party’s familiar faces like Hina Bhat and Darakhshan Andrabi were excluded from the candidate list. In 2014, Bhat had declared she would take up an AK-47 if Article 370 were revoked. BJP opted to keep her and others out. Instead, the party focused on bringing in leaders from the Centre and Jammu to highlight their contributions to peace and development. However, the BJP might struggle to get even a single seat in Kashmir, while in Jammu with the Congress not mounting a strong challenge, the BJP could find itself at an advantage.

Many more players joined the game. The entry of the banned Jamaat-e-Islami through the backdoor was as intriguing as Engineer Rashid’s grand appearance. Rashid and the Jamaat formed an alliance, while in the parliamentary election, Sajad Lone’s People’s Conference and Apni Party had come together, with the BJP tactically supporting them. After Rashid’s win from North Kashmir, the Apni Party and the Peoples Conference were relegated to the background. They are now abusing the BJP more than others. The Jamaat presented itself as if it was sad to have been absent from the democratic process for 35 years. The party which was part of the poll boycott all these years is now singing the praises of democracy.

In Jammu, the contest is between the major players—the Congress, the NC and the BJP—while in Kashmir, it is the NC has an edge. Sugra Barkati, the daughter of a separatist, filed nominations from two constituencies against Abdullah, who chose not to contest against her in her stronghold, Beerwah.

In this election season, Kashmir has seen a new leadership emerge, from Aga Ruhullah Mehdi in the NC, Waheed Para and Iltija Mufti in the PDP and Abrar Rashid to Sugra Barkati. Ruhullah is already making waves in Parliament and if others enter the assembly, it will reshape the political leadership of the Valley that has remained confined to the Abdullahs and the Muftis.

The 1987 election was a tipping point, as widespread rigging led to a prolonged insurgency and left Kashmiris feeling disillusioned after investing their energies in the voting process. The 1996 assembly election is perceived as coercive, with security forces said to have forced people to queue up outside polling booths. In 2002, the PDP promised to end the violence that had plagued Kashmir, vowing to dismantle the counter-insurgent Ikhwan and Special Operations Group. In subsequent years, significant confidence-building measures like the opening of the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad Road was seen.

In 2008, massive protests erupted, resulting in the deaths of over 100 demonstrators over transfer of land to the Shri Amarnath Shrine Board. The separatists shut down Kashmir for six months. However, by the end of that year, the NC returned to power with people voting in large numbers. In 2010, militants who had gone to Pakistan for arms training in the 1990s began returning to Kashmir, marking yet another confidence-building measure. The 2014 election was framed as a means to keep the BJP at bay but ultimately led to a PDP-BJP coalition government.

This assembly election in J&K is underway at a time when the separatist movement has largely faded. The pressing question now is whether statehood of J&K, its demographics and land will be preserved as they are the focal points of this election.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

From the demand for azadi in 1990, the Government of India promising “anything short of azadi” in 1996 to the autonomy resolution in 2000, and now the struggle to preserve its identity within a Union Territory, Kashmir’s politics has traced an unusual trajectory. It seems to become increasingly strange with each turn.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Players, The Politics')