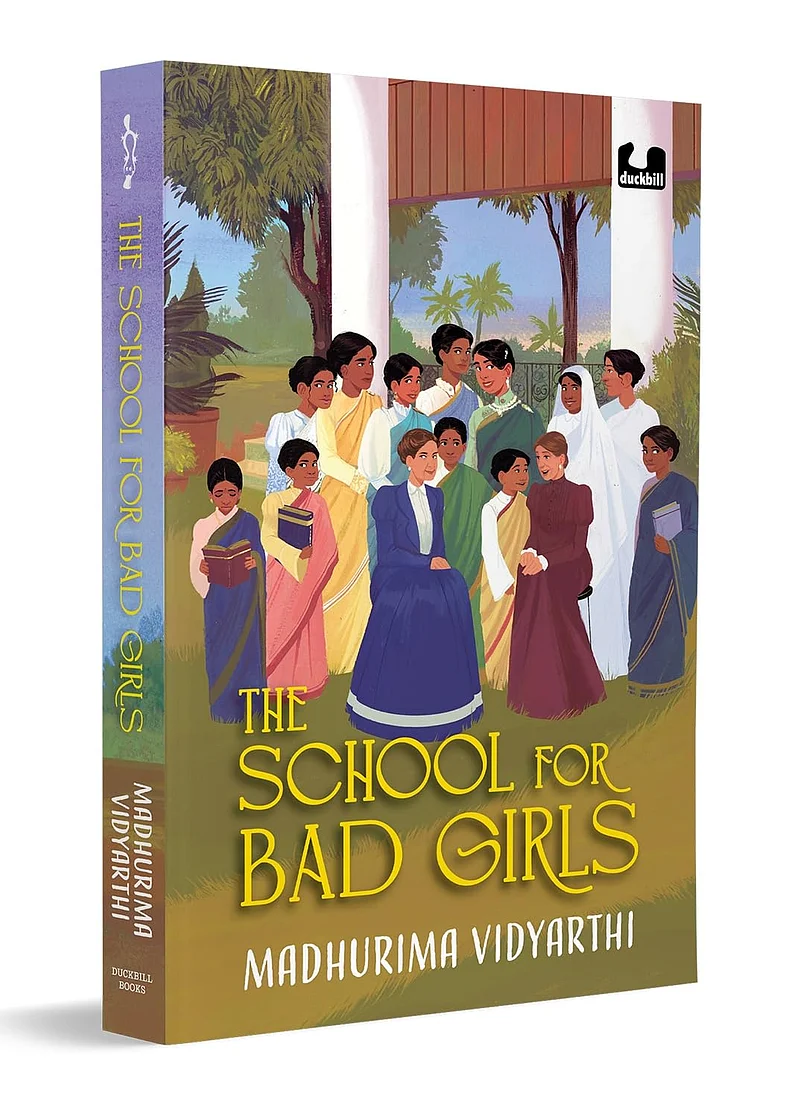

The School for Bad Girls by Madhurima Vidyarthi blends history and fiction to narrate the struggles of pioneering women like Kadambini Ganguly, India’s first female doctor.

Told through the eyes of Kumud, a child-widow turned student, the novel highlights the battles of women’s education in colonial Bengal.

This book calls out to be judged by its title – The School for Bad Girls will provoke readers to wonder what this school was and how the “bad girls” became medical graduates – well, one medical graduate, Kadambini Ganguly, the first Indian woman to become a doctor in colonial times. Madhurima Vidyarthi tells us the story of an era when women were looked down upon and relegated to drawing rooms and kitchens. Considered ‘delicate creatures’ by the British, they were deemed unworthy of any kind of education. Yet there were educators in Bengal, both English and Bengali, who believed girls deserved a shot at learning. The girls chosen for the school that was set up were child widows shunned by their families, orphans, Brahmos, even Christians – a mix shunned by conservative Hindu society.

Vidyarthi tells her story through the eyes of Kumud, a child widow brutally thrown out of her home and rescued by Panditmoshai Dwarkanath Ganguly, whose daughter Bidhumukhi later married Upendrakishore Raychoudhury. Kumud is put into the Banga Mahila Bidyalaya system and gradually takes to learning her letters and more. We discover Kadambini Ganguly through her eyes and also through Kadambini’s diary. For Kumud, Kadambini is an idol – today we would call her a fangirl – and she also highlights the weight of expectations Kadambini bore. To be the first woman to do anything in colonial India was difficult, and though another pioneer, Chandramukhi Basu, is mentioned, she receives only passing reference.

Kumud is the commentator whose experiences, backed by her education, give her a maturity that enables her to project a fair picture of the life of the times for girls who dared defy societal norms. She also adds a note of blushing romance that young adults will enjoy.

Much of the story is epistolary at first, written in the meticulous, formal style of the period. Kadambini’s story is woven with the wider struggles for women’s education in colonial Bengal, encompassing the fallouts with different factions – Keshab Chandra Sen, for example, believed only in basic education for women and married his daughter to the Maharaja of Cooch Behar when she was under 14.

At Banga Mahila Bidyalaya, girls were educated on par with boys – trained in Science, Mathematics and English, though they also learnt to lay the table and embroider, so that the domestic arts were not neglected. The school became a battleground for these girls as they challenged restrictions imposed by both society and the colonial government.

The struggle for funds and the difficulties of study weighed heavily on the teachers and Panditmoshai. Meanwhile, Kadambini fought to raise her academic standard so that she could enter Calcutta University, once the British grudgingly agreed that women could sit the entrance test. Yet there remained a persistent belief in colonial society that women could not work and therefore had no real need of education – a view ironically aligned with conservative Hindu mores, which treated child widows as servants and banned them from books. The girls’ fight was to prove they were not burdens on society, and to reclaim the lives snatched from them when they were too innocent to understand what was happening.

We have met such difficulties before in the novels of Sarat Chandra and Tagore, but Vidyarthi grounds the issues of marriage, caste and education firmly in historical perspective in this cross-genre work of hers.

Bethune later became a college where girls like Kadambini could study the fine arts, and unlike the school, it admitted Christians. Initially there were only two students; another girl, a Christian from Cawnpore, joined Kadambini, setting yet another benchmark in inclusion. Chandramukhi Basu went on to become Bethune’s first Indian woman principal – in fact, the first in Southeast Asia. Kadambini ultimately joined Medical College, confirming her rank as trailblazer for women in science and medicine, but also proved that women could balance home and profession. She married her beloved Panditmoshai, Dwarkanath Ganguly – a widower – just twelve days before joining Medical College, and went on to have eight children.

The blend of fictionalised and real characters makes the story relatable. Vidyarthi’s strength lies in her dialogue and her accounts of everyday domestic events. It helps that she herself is a doctor, and that her own school, Bethune, is the one she is ultimately writing about, since the Banga Mahila Bidyalaya merged with Bethune and, in a sense, became a school for even “badder” girls – those who learnt to stand on their own two feet.