Recognising the potential of the most backward classes, the BJP-led central government awarded the Bharat Ratna to former Bihar chief minister, the late Jananayak Karpoori Thakur.

By 2005, the EBCs, non-Yadav OBCs, and Pasmanda Muslims rallied behind Nitish Kumar, whose alliance with the BJP secured upper-caste and Baniya votes as well.

With Hindu EBCs forming one fourth of the population, they now demand proportional representation.

Seated in the verandah of his modest concrete home in Muzaffarpur, around 90 kilometres from Patna, 50-year-old Naresh Sahni speaks with quiet certainty. “Today, 36 per cent of the population is forming the government. Whichever side gets these votes will certainly form the government,” he says. The “36 per cent” he refers to are members of Bihar’s Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs), a loose collection of more than a 100 small, heterogeneous castes. Around 10 per cent of them are from Muslim EBC communities. Sahni himself belongs to the EBC. The Sahni or Mallah community comprises nearly 20 sub-castes whose primary occupations are river-related, mainly fishing and boating. Recent political efforts to woo the EBCs, known as Panchpawania, show that Naresh Sahni’s claim is no exaggeration.

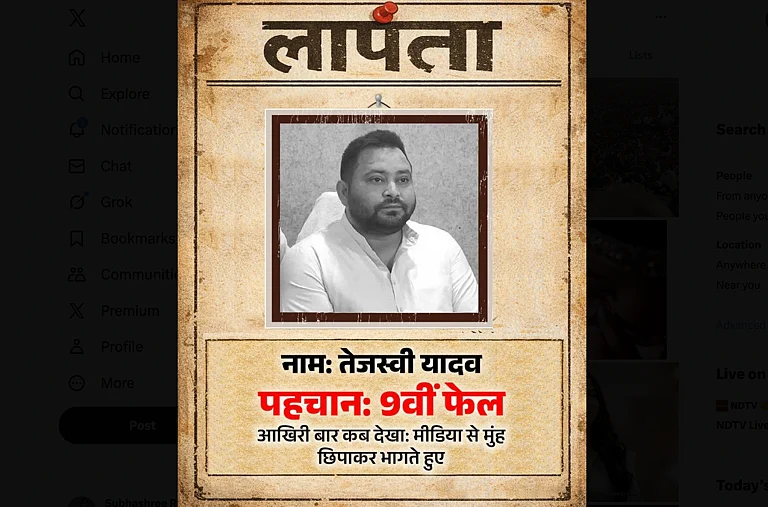

Recognising the potential of the most backward classes, the BJP-led central government awarded the Bharat Ratna to former Bihar chief minister, the late Jananayak Karpoori Thakur, the state’s most prominent EBC leader, belonging to the Nai (barber) caste. Recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi began his election rally in Samastipur district from Karpoori Thakur’s village, Karpoorigram. Jagruti Thakur, granddaughter of Karpoori Thakur, is contesting the assembly elections on the Jan Suraaj Party (JSP) ticket from the Morwa assembly seat. The state’s ruling party, the Janata Dal (United) or JD(U), launched the Atipichhda Samvad Rath Yatra in September to consolidate EBC support. Meanwhile, Bihar’s main opposition party, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), appointed Mangani Lal Mandal, a member of the Dhanuk community, which falls under the EBC category, as its state president. Earlier this year, RJD leader and former deputy chief minister Tejashwi Yadav held the Atipichhda Jagao Rally (Awaken the Extremely Backward Classes Rally) to attract EBC voters.

Similarly, the Congress party, for the first time, established an Extremely Backward Class cell within the organisation, headed by Shashi Bhushan Pandit, a Kumhar by caste. In addition, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi recently met members of the Lohar, Halwai, Mallah and other EBC castes. To further consolidate EBC votes, India Alliance brought Mukesh Sahni’s Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP) and IP Gupta, an influential Tanti caste (falls under EBC) leader in its fold.

The EBCs comprise over 100 castes, mostly artisans like Badhai (carpenters), Kumhar (potters), and Lohar (ironsmiths), as well as service providers such as Nai and Dhobi (washermen). Scattered across villages, they are present in small numbers, historically brought in to serve dominant castes. In Jamira village, Bhojpur district, Krishna Pandit, a Kumhar, says, “The influential castes of this village brought our forefathers to make earthen pots. Now we have around 40 houses and 200 votes.” Though individual EBC castes are smaller in size—Telis form 2.81 per cent, Mallahs 2.6 per cent, Kanus 2.21 per cent, and Dhanuks 2.13 per cent—together, their 120 sub-castes form a significant bloc.

The category’s origin dates to the 1950s when two lists of backward castes, Annexure 1 and Annexure 2, were created. The first covered the “extremely backward,” but data limitations delayed affirmative action. In 1971, Chief Minister Karpoori Thakur formed a 20-member panel to identify EBCs but had to dissolve it. Later that year, the then Chief Minister Bhola Paswan Shastri established the Mungerilal Commission, led by freedom fighter and ex-minister Mungerilal.

The earlier list of Backward Classes included 94 castes, which rose to 128 in the Mungerilal Commission’s review. In its 1976 report, the Commission identified 94 of these as socially and economically extremely backward. It warned that without proper classification, the more advanced sections among the backward classes would monopolise reserved benefits, leaving the truly backward excluded. It recommended that states classify these communities according to their level of development to ensure fair representation. This marked the emergence of the most backward classes as a political force. When Karpoori Thakur became Chief Minister again in 1978, he accepted the Mungerilal Commission’s report and implemented reservations: 12 per cent for OBCs, eight per cent for EBCs, and three per cent each for women and economically backward upper castes in government jobs. Though they gained reservations, social respect was still denied to them.

They remained under the dominance of upper-caste landlords. When Lalu Prasad Yadav came to power in 1990, he increased EBC reservation from 10 to 14 per cent, later raised to 18 per cent after Jharkhand’s separation in 2000. But Lalu’s impact went beyond quotas—his leadership brought dignity and protection from upper-caste oppression. Pushpendra, a former professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), says, “In his first regime, Lalu Yadav’s people stood against upper-caste tyranny, so they became his strong vote bank.” Naresh Sahni adds, “Lalu Yadav gave us the right to speak. He awakened political hunger in our community.” Rajkumar Thakur Nandvanshi, a Nai, from Muzaffarpur recalls, “Ambedkar gave us equality in the Constitution, Karpoori Thakur gave us reservation, but Laluji gave us dignity. Earlier, we could not even sit before upper castes. He ended that.” Krishna Pandit of Jamira village agrees, “Laluji uplifted us. He taught us to speak.” Lalu Prasad Yadav had sensed a silent consolidation before the 1995 assembly elections. During his campaign, he would often tell public meetings that a genie would emerge from the ballot box—and it did. EBCs, Dalits, Muslims, and Yadavs voted overwhelmingly for him. He won 167 seats and became chief minister for the second time.

However, once the EBCs gained dignity, they also wanted political participation, which they did not get. As Lalu’s tenure progressed, the Yadavs began to see themselves as dominant, and reports of their oppression of Dalits and EBCs grew. Krishna Pandit recalls, “When Laluji went to jail in the fodder scam, there were other educated leaders in the party, but he made his wife Chief Minister. That angered people.” “Lalu Yadav awakened political hunger but did nothing to satisfy it. You made us aware of our hunger, but if you don’t feed us, we will go elsewhere. So, the EBCs turned to the JD(U),” he adds. During Lalu’s rule, EBC representation in government was negligible. Despite forming 32 per cent of the population, they made up only five per cent of MLAs. Over time, the Yadavs became the new upper castes, often clashing with Dalits and EBCs. Rajkumar Thakur says, “Laluji gave us respect, but when his caste started exploiting us, we drifted towards Nitishji.” Professor Pushpendra notes, “In his first term, Lalu Yadav challenged upper-caste domination, but later his own caste became oppressive.”

By 2005, the EBCs, non-Yadav OBCs, and Pasmanda Muslims rallied behind Nitish Kumar, whose alliance with the BJP secured upper-caste and Baniya votes as well. Nitish inducted four EBC ministers in his first cabinet—about 15 per cent of the total—and reserved 20 per cent of panchayat posts for EBCs. In the 2006 panchayat elections, over 50,000 EBC representatives won.

This reservation encouraged people like Krishna Pandit to contest elections. “I first contested for mukhiya (village head) in 2006 and lost by seven votes. I tried again in 2011 and won. In 2016, my seat became general, and I lost as Yadavs and upper castes didn’t support me,” he says. “I got just 200 votes, mostly from my Kumhar caste.” Once Lalu’s ‘genie’, the EBCs have now become Nitish’s most reliable vote bank. “Around 80 per cent of EBC voters are still with JD(U),” says Pandit.

With Hindu EBCs forming one fourth of the population, they now demand proportional representation. The JD(U) has fielded 19 EBC candidates, the BJP 10, and the RJD 21, including five Muslim EBCs. Yet, many remain wary of returning to the RJD. Pandit says, “I am a die-hard RJD supporter, but Yadavs think they are all Lalu Prasad Yadav. EBCs have a problem with this.”

Still, discontent lingers. Rajkumar Thakur says, “We are Nais by caste, but we cannot afford to open proper salons. More than half the good salons are owned by other castes, and Nais work there on daily wages. If the government gave us Rs 5-7 lakh through a Kesh Kala Board, we could open our own salons.”

Fear of Yadav domination continues to keep EBCs and Dalits away from the RJD. Pushpendra explains, “Criminal incidents may have risen in Bihar, but the daily lawlessness of Lalu’s later years still haunts voters.” Tejashwi Yadav has publicly urged his community to rebuild ties with Dalits and EBCs, but little has changed on the ground. In 2023, in Khusrupur, Patna, a Mahadalit woman faced atrocities at the hands of Yadav men. When she refused to withdraw her FIR despite pressure from a local RJD MLA, her family stood firm. Ashok Das, her relative and an RJD member since 1995, says, “Until recently, our people were beaten if they refused to work in Yadavs’ fields. But now we are fighting in court, and they don’t trouble us.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Umesh Kumar Ray is a Bihar-based independent journalist.

Outlook’s November 11 issue, titled "Caste is the Biggest Political Party in Bihar," explores how caste plays multiple interconnected roles in seat-sharing and coalition-building in the land of the setting sun. It Appeared as 'Extreme People'