Miriam Koshy uses stitching as a way to heal.

Her textile art transforms medical gauze into symbols of repair.

Soul Stitch Circles build community through meditative stitching.

My earliest understanding of art’s therapeutic power emerged not in a studio but in the Occupational Therapy wing of Nur Manzil Psychiatric Hospital, in Lucknow, where my father worked. As a child, I watched patients steady trembling hands by drawing, collaging or stitching simple patterns, their creations unflinching in their rawness. A smear of paint might betray anguish. A row of uneven stitches could map manic energy. I was too young to grasp the clinical nuances, but I absorbed the truth that creativity could be a bridge between fractured inner worlds and the outside.

Those early encounters planted a seed. I began to see embroidery not as decoration but as a way to navigate my own emerging emotional terrain. The patients’ raw, unfiltered expressions—stitches too tight, colours clashing violently, patterns dissolving into chaos—taught me that art does not demand prettiness, only honesty. Years later, this lesson resurfaced in my own art practice, now informed by Hungarian-born Canadian physician Gabor Maté’s teachings on trauma’s corporeal (physical) imprint.

I returned instinctively to the needle, remembering how those quiet rooms at Nur Manzil held space for unravelled minds to slowly, stitch by stitch, find their way back to themselves.

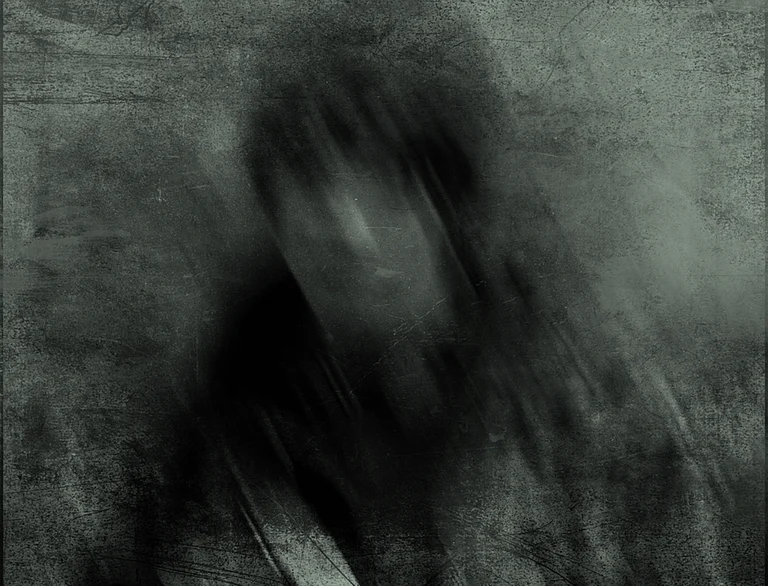

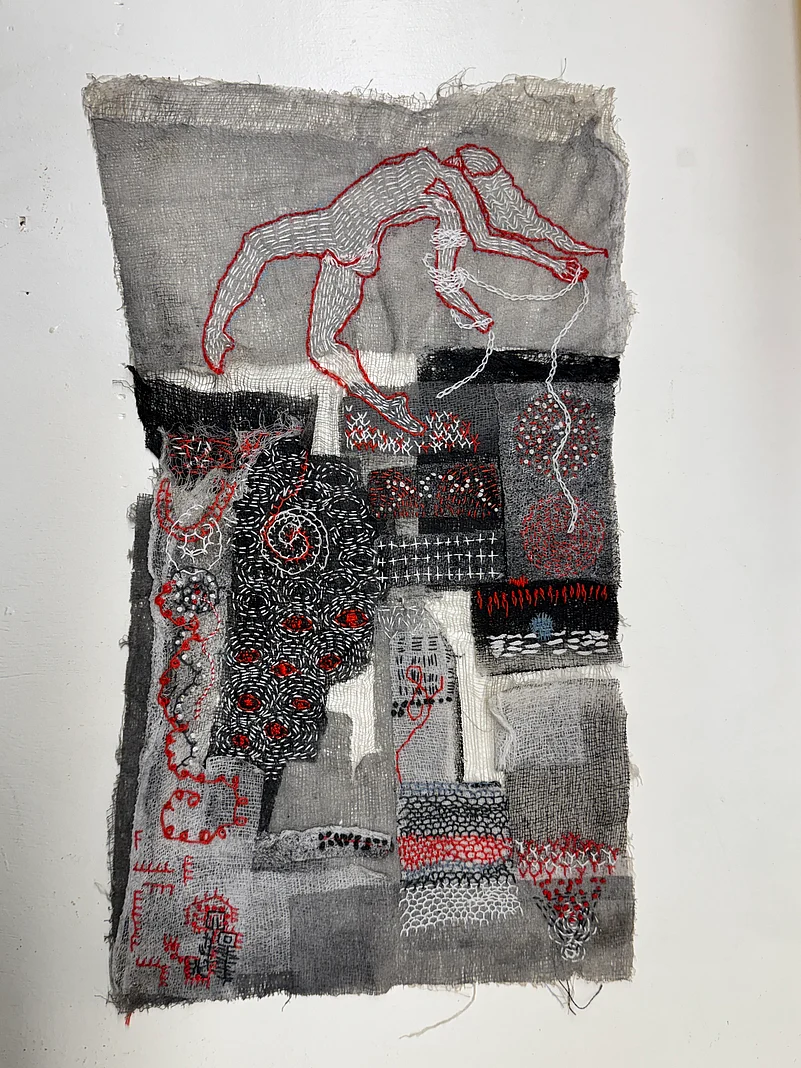

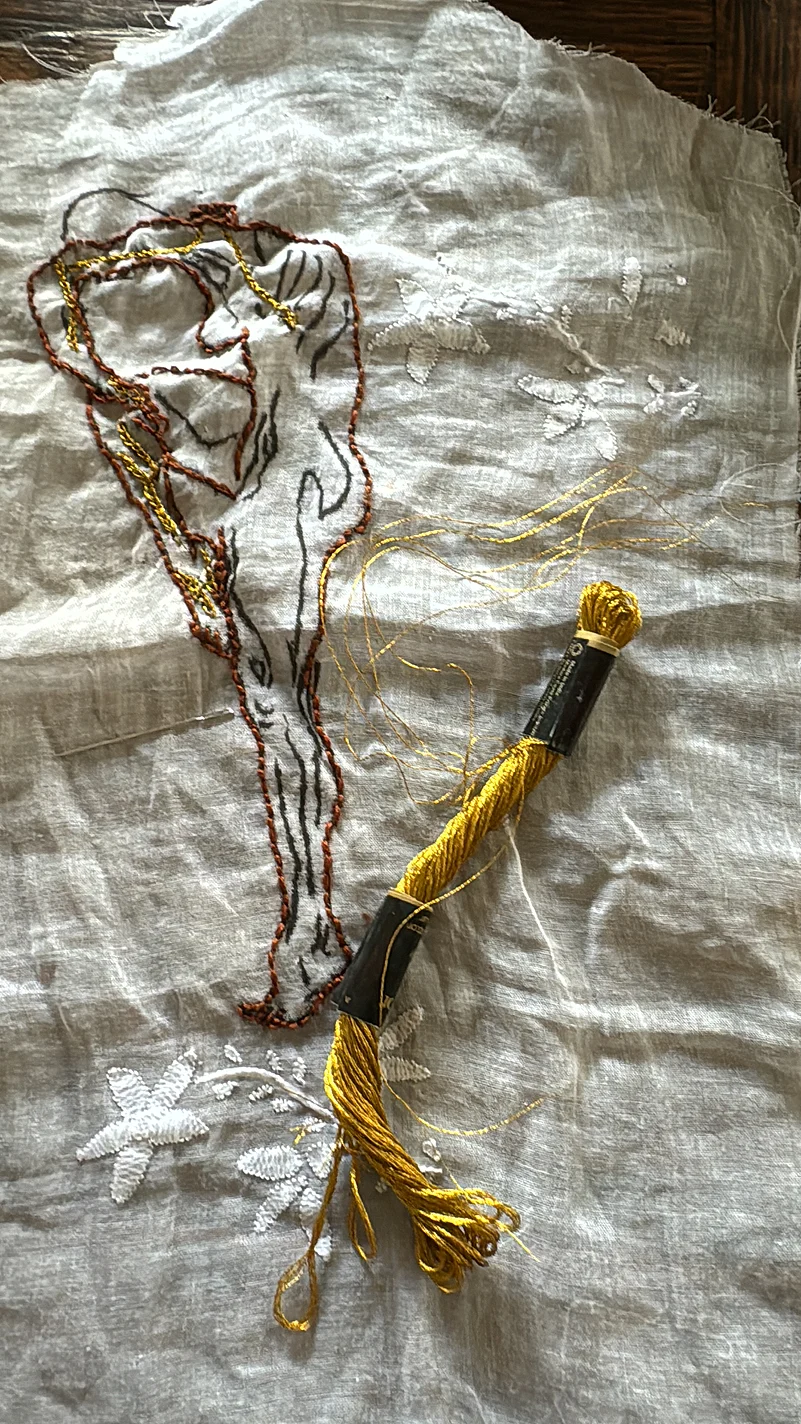

I use stitching as a way to map the unspoken language of grief and trauma held in my body—an approach that resonates deeply with Maté’s reminder that the body says what words cannot. In my work, each puncture of the needle, each pull of the thread, becomes a somatic or bodily release, a way to externalise the tension, numbness or fractures that have been silenced. His concept of compassionate inquiry mirrors my process. Rather than avoiding pain, I embroider organic, swirling lines that trace nerve pathways, or dense, knotted clusters where trauma has crystallised—not to retraumatise, but to witness with curiosity and care.

Maté’s work emphasises that trauma is not what happens to you, but what happens within you — a truth that unfolds in my practice as I stitch onto fabric pressed against my skin, transferring the body’s imprint into the work. The repetitive, meditative nature of stitching aligns with his advocacy for mindfulness in healing, creating a rhythmic space where the nervous system can regulate. The resulting pieces are artefacts of survival, echoing his belief that healing is not an event, but a process of reconnection — to the body, to emotion and to community. Through this practice, I reclaim agency over my body’s narrative, one stitch at a time, transforming Maté’s insight that the wound is where the light enters into a tactile, luminous reality.

In a world unravelling under the weight of ecological collapse, political violence and collective trauma, I have turned to textile art as both compass and sanctuary. My practice—spanning meditative stitch journals, somatic embroidery, land altars and communal prayer flag rituals—uses thread not as decoration, but as a means of repair: of the self, the community and the more-than-human world. Rooted in childhood encounters with healing at Nur Manzil and honed through years of embodied inquiry, this work insists that stitching can be a radical act of witnessing. It is where personal and planetary grief intertwine, where gauze becomes a metaphor for permeable boundaries between wound and wisdom, and where slow, deliberate handwork becomes an antidote to the violence of disconnection.

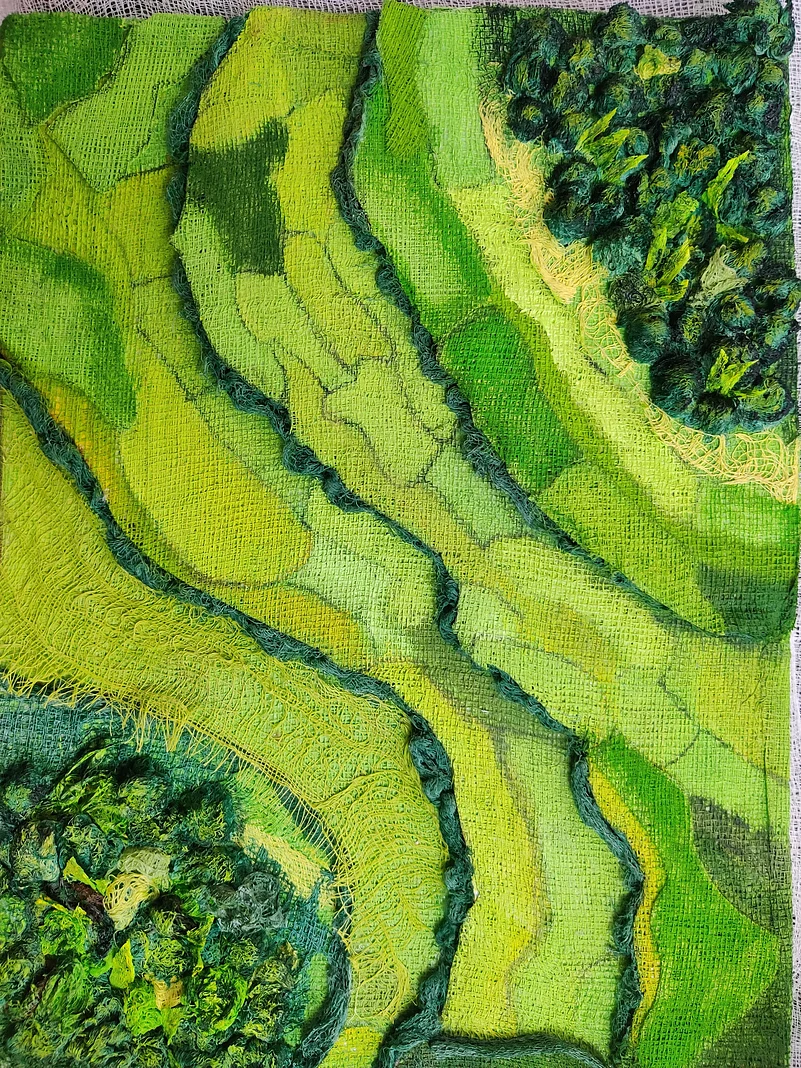

Here, gauze takes on ecological resonance. Layered over rubbings of bulldozed soil or embedded with mangrove mud, it becomes a bandage for the earth itself. The process is ritual. Each element confronts the violence of extraction while asserting the land’s sacredness. A cashew blossom stitched in gold thread is both celebration and elegy; a river mapped in chain stitch acknowledges its pollution while invoking its persistence. By framing these textiles as sacred objects—hung like temple toranas (festive gateways) or laid out as ceremonial palls—I invite viewers to confront the violence of ecological loss while also remembering the land’s enduring sanctity.

This project grows from the belief that to stitch the land is to acknowledge our entanglement with it. When I embroider the roots of a mangrove, I am also stitching my own dependence on its tidal breath; when I quilt a map of a vanishing river, I am tracing my complicity in its fate. ‘Altars to the Land’ is not nostalgia, but an act of reverence and resistance, a call to re-enchant our relationship with place—to see the land not as a resource, but as kin. In these cloth shrines, grief and gratitude warp and woof, weaving a fragile hope: that art might help us remember how to belong to the world again.

The first time I pressed gauze into the red laterite soil of Goa’s ravaged hillsides, I understood this was not art, but autopsy. The fabric emerged stained the colour of a fresh wound, its threads clinging to the earth like sutures on raw flesh. My practice is born of ecological grief—the profound sorrow for a world unravelling through climate collapse, deforestation and the slow violence of development. But this grief is not passive; it is what ecofeminist philosopher Val Plumwood called the work of mourning as resistance, where ecological grief becomes an active witness. I wield needle and thread as tools of both lament and protection, stitching altars that make visible the intimate kinship between bodily trauma and landscape trauma.

Ecofeminism teaches us that the exploitation of nature mirrors the subjugation of marginalised bodies—both rendered as territories to be mapped, extracted and discarded. When I embroider Goa’s fish species onto surgical gauze, or stitch mangrove roots with threads dyed in their own tannins, I am practising what scholar Astrida Neimanis terms hydrofeminism: recognising our bodies as part of water’s cycle, our breath entangled with the photosynthesis of palms. The gauze becomes a membrane between personal and planetary pain—the same material that dresses surgical wounds now bandages the land’s suffocation under concrete.

This is the alchemy of my work: transforming the medical materiality of gauze into sacred stitched text. Each stitch enacts Donna Haraway’s call to stay with the trouble—not to fix, but to witness. The process mirrors Melanie Klein’s psychoanalytic notion of reparation—not perfect healing, but the courage to let wounds breathe. My practice, rooted in ecofeminism’s insistence that the personal is planetary, suggests that every mended tear in fabric is a suture in the web of life. To stitch is to say: I see the wound. I am part of it. And like spider silk that strengthens when pulled, our collective grief, woven together, might yet hold.

If my somatic work stitches personal trauma, my ongoing art project, Altars to the Land, is a devotional practice in thread which seeks to mend ruptures between humans and the living world. These textile shrines honour Goa’s ecosystems—mangroves, laterite plateaus, monsoon forests —not as scenery, but as kin. Each piece is a meditation on interdependence, stitching together the stories of cashew blossoms, fiddler crabs, toddy palms and mycorrhizal networks—underground systems formed by fungi that connect plant roots, enabling them to share resources and information—the often-unseen threads that bind us to the more-than-human world.

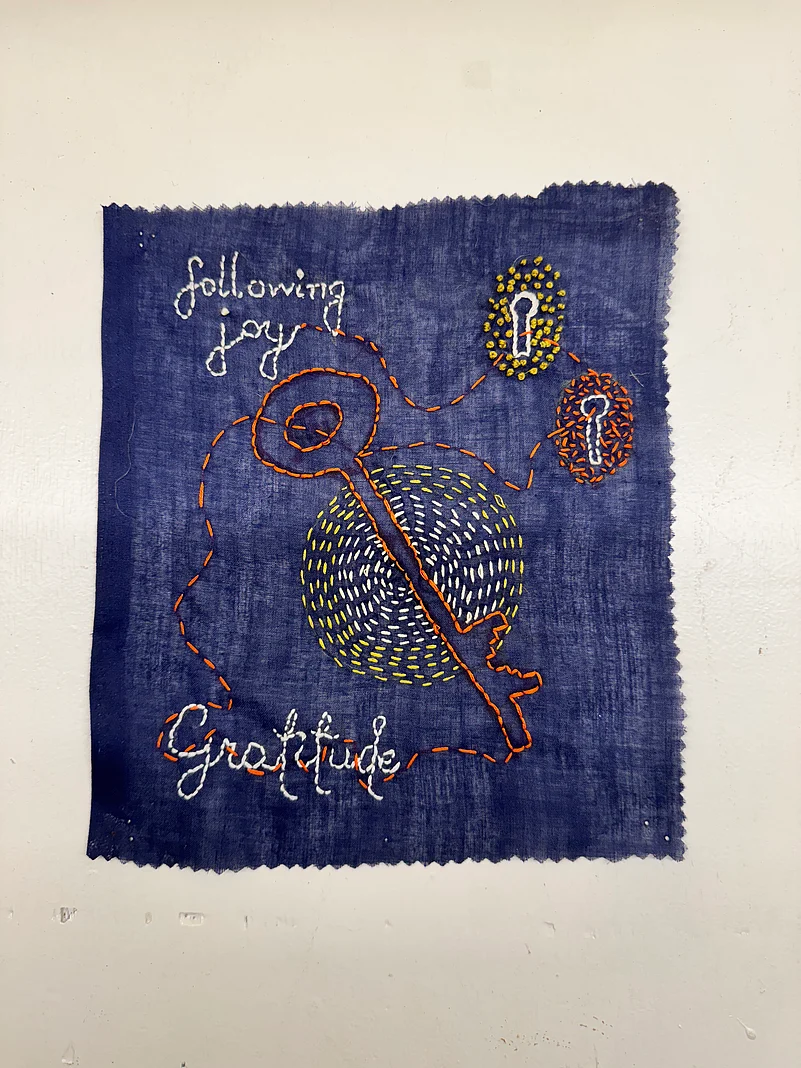

Healing, as Maté reminds us, requires reconnection—not just within ourselves, but between each other. My Soul Stitch Circle was born from this need. We gathered to create meditative stitch journals and prayer flags, transforming solitary grief and disconnectedness of the self and others into collective testimony. The act of sewing—whether by hand or machine—becomes a meditative practice, a form of protest, and a way to build community. From stitch circles that address ecological grief to embroidery projects that honour Palestinian lives lost, stitching serves as both a personal and communal act of resistance and restoration.

We sit in shared silence, needles in hand, stitching not just fabric but fragments of our inner landscapes onto cloth. These are our meditative stitch journals: slow, intuitive embroideries that unfold like whispered conversations with the self. There are no rules, only rhythm—the pull of thread through linen, the knotting of emotions into tangible form. Some days, the stitches are tight and orderly, a measured attempt to contain chaos; other times, they sprawl like wild vines, following the restless energy of an unsettled heart. The journals become sacred ledgers, mapping grief, gratitude and everything in between—one imperfect stitch at a time.

Together, we also stitch our petitions into prayer flags—our own vernacular of hope, release and collective longing. We ink them with turmeric and indigo, stitch on handwritten petitions, and embroider symbols that speak what words cannot: a spiral for resilience, a portal for new beginnings, a butterfly for metamorphosis. Unlike prayers sent skyward, these are anchored in the tactile—thread as a covenant between hands and heart. The prayer flags carried our personal petitions for the way of being and life we wish to create for ourselves.

In these circles, stitching becomes a means of radical compassion and presence. The repetitive motion of needle and thread is grounding and therapeutic, offering a way to process grief when words fail. Unlike the digital world’s demand for instant reaction, the needle insists on patience. A single stitch requires breath. A knot demands deliberation. This slowness is a political act in a culture that monetises attention and denies grief its rightful space.

Samplers, pieces of embroidery made to practise or demonstrate needlework stitches, were an important part of girls’ education for centuries. In Britain, girls stitched samplers from the 17th to the early 20th centuries, gaining skills such as literacy, counting and dexterity they would need to be successful wives, mothers and mistresses of households or, if they needed to earn a living, effective domestic servants or participants in the textile trades. Many girls throughout the British Empire—in India, Australia and Sierra Leone—were also made to stitch.

The foundations of my stitch vocabulary began under the whirring ceiling fans of La Martiniere’s needlework classroom, in the paradox of a colonial-era sampler-making curriculum that was part of the Socially Useful Productive Work (SUPW) module at Lucknow’s La Martiniere Girls’ School. It was here that I first learnt the 400-year-old chikankari embroidery under the exacting gaze of my SUPW teacher. The precision demanded by this craft was designed to create ethereal white-on-white embellishments for Lucknow’s elite. Yet this training in precise perfection became the unlikely foundation for my therapeutic material gauze practice, where stitches are not meant to disappear but to testify, colliding with the raw urgency of somatic stitching.

Rozsika Parker’s seminal text The Subversive Stitch frames this transformation. She documents how embroidery, long dismissed as women’s work, became a site of covert resistance—where the very stitches meant to enforce feminine decorum were weaponised by suffragettes, feminist artists and postcolonial makers. The same hands that stitched phanda knots smaller than poppy seeds would later use surgical sutures to map trauma onto gauze, completing a circle Parker might call ‘the education of the rebellious needle’.

My practice extends this subversion into three contemporary realms.

Where chikankari requires fine mulmul cotton, I choose surgical gauze—a material associated with wounds, not ornament. This shift mirrors Parker’s observation that the materials of embroidery carry social histories. Gauze, with its refusal to hold orderly stitches, became my rebellion against chikankari’s flawless craftsmanship—yet the tradition gifted me something indispensable: the knowledge that to mend is to pay relentless attention. Somewhere among the countless afternoons spent stitching in school, I learnt that embroidery is a language; in my practice now, I use that language to spell out words the body has swallowed. My stained, puckered gauze rejects chikankari’s pristine surfaces. The gauze’s transparency becomes political: it refuses to conceal the labour of repair.

Traditional chikankari motifs follow strict geometric repetition. This exacting practice, meant to adorn royal garments, became an unexpected framework for mending trauma. Where chikankari demands perfection, my current work embraces rupture—yet the muscle memory of those tiny, measured stitches persists. In my somatic work, stitches become erratic documentation: a French knot swells like scar tissue, a satin stitch frays to mimic nerve damage. Here, I engage Parker’s argument that the stitch can be a word, the embroidery a diary. My taipchi, a basic running chikankari stitch, no longer marches in orderly rows but traces the naqsha (map) of my trauma lines I seek to witness.

Parker notes that Western embroidery traditions isolated women with their hoops, while non-Western practices like kantha (a form of embroidery associated with pastoral living) often involved communal circles. My Soul Stitch Circles hybridise these legacies: we use chikankari’s precise techniques but subvert their solitary mastery. When teaching phanda knots, I emphasise their new purpose—not to perfect a motif, but to map where pain clusters in the body. The circle becomes what Parker calls a space where the personal needle becomes a collective voice.

This lineage culminates in my land altars. The mangroves I embroider onto gauze are not idealised Mughal florals but ecosystems gashed by development; my stitches do not embellish but suture.

Central to all these practices is gauze—a material both mundane and profound. For me, it is more than a material, it is a meditation. The material breathes like skin, its grid-like structure echoing the Cartesian mapping of trauma onto the body—a way of charting or plotting it as points on a grid—while its gaps insist that some things cannot be fully contained or repaired. By embroidering directly onto it, I ritualise the act of tending to injury. French knots cluster like scar tissue; running stitches mimic sutures; deliberately frayed edges speak of erosion. Yet gauze also transforms under the needle, becoming a veil for memory, a ghostly parchment on which the body’s stories are written. When layered, it creates palimpsests (layers with faint traces of earlier marks) of pain and repair, where what shines through one layer is obscured in another, much like the way trauma lingers in the nervous system.

Gauze is not just my material but my collaborator in exploring what it means to be simultaneously vulnerable and resilient. The medical and poetic duality remains central while allowing room for ecological and communal dimensions of my work to resonate.

In Altars to the Land, gauze stained with laterite soil becomes a palimpsest of ecological harm and endurance. In somatic work, its fragility mirrors the body’s vulnerability. In the Soul Stitch Circle, its permeability symbolises our shared humanity—what we absorb from one another, what we let pass through.

To stitch is to participate in an ancient lineage of repair—one that acknowledges brokenness while insisting on beauty. When I embroider a name onto a land altar or knot a prayer flag with others, I am not just making art. I am rehearsing a way of being that honours rupture and resilience in equal measure. The needle’s path is never linear—it loops, crosses, and sometimes snaps. But as any stitcher knows, even broken thread can be woven anew. My practice, spanning personal, communal and ecological realms, is rooted in three convictions: trauma demands material witness, healing is interdependent and slowness is resistance.

In the end, these textiles are more than objects. They are maps for how to live: with attention, with tenderness, and with the quiet faith that every stitch—no matter how small—contributes to the mending of the world.

In its August 21 issue, Outlook collaborated with The Banyan India to take a hard look at the community and care provided to those with mental health disorders in India. From the inmates in mental health facilities across India—Ranchi to Lucknow—to the mental health impact of conflict journalism, to the chronic stress caused by the caste system, our reporters and columnists shed light on and questioned the stigma weighing down the vulnerable communities where mental health disorders are prevalent.

This copy appeared in print as "The Soul Stitch Circle".