Summary of this article

The July 2024 student-led anti-quota protests escalated into a nationwide movement that toppled Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year rule.

An interim government under Muhammad Yunus ushered in political uncertainty, generational shifts and new electoral formations.

Nearly two years later, voters face rising economic pressures and unresolved demands for justice as they decide whether the “36th of July” will translate into lasting democratic change.

For a long time in the July of 2024, people in Bangladesh felt as if time had broken, with some calling August 5 the “36th of July”, the day, the long-term “authoritarian government” of Sheikh Hasina collapsed after a major confrontation that initially began as an anti-quota protest and later on turned into a nationwide uprising against corruption, dynastic politics and state violence.

In those long weeks, more than 500 people, mostly young, were killed as campuses slowly began turning into battlegrounds and eventually when the military refused to intervene in the violent protests, Sheikh Hasina, the former prime minister, was forced to flee to India, resulting in Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus taking charge of an interim administration.

Almost two years later, on Thursday, February 12, Bangladesh voted to choose the first elected government after that rupture. What’s different this time is that former student leaders, many from the National Citizen Party, moved from the streets to the ballot, even as the Awami League remains barred and the political field reshapes itself around the BNP, Jamaat-e-Islami and new Gen-Z formations.

For a country grappling with major issues of inflation, unemployment and unresolved justice for those who were killed in the violence, this election is about giving chance to stability, accountability and survival.

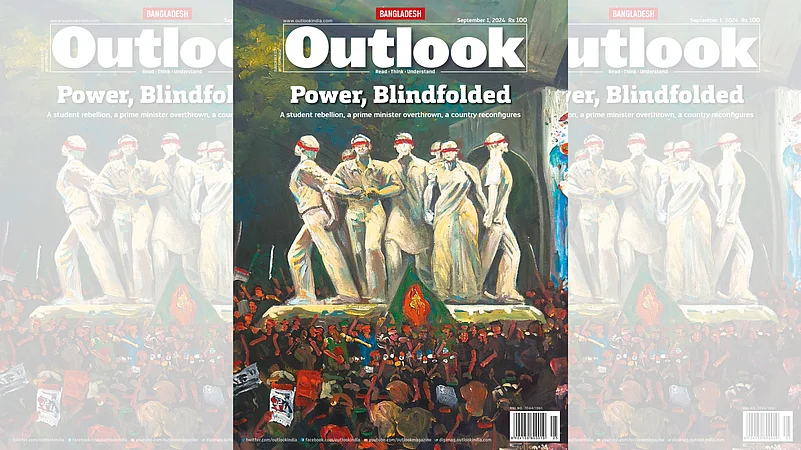

In our September 2024 issue dedicated to Bangladesh, ‘Power, Blindfolded’, Outlook sought to bear witness to that rupture, to document not only the euphoria, but the fractures beneath it.

The rise of the student protest and the force that carried it, revealed the power of a young generation that refused to step back. One of the pieces asked what the July–August upheaval meant for minorities. Students from all religions and castes took part in the movement, with many of the victims being from minority communities.

One account followed Shazid, who lay in a coma for ten days before dying of brain injuries. Hasina’s era ended, but for families like his, victory was bittersweet. The cost of change was measured not in slogans, but in funerals.

Another essay traced the deeper roots of the anti-quota movement, years of anger over systemic discrimination, shrinking democratic space and a government that blurred the line between mandate and monopoly. From New Delhi, the buzzword was “strategic patience.” Sheikh Hasina had been India’s closest regional ally; her sudden flight sent diplomatic tremors across the South Block.

The upheaval was also placed in a longer arc, recalling 1971 even as a new great-power contest loomed over Dhaka. Questions followed the so-called “Gen Z revolution”: with Jamaat-e-Islami figures visible among protestors, who would inherit the movement?

The myth of Bangladesh’s “economic miracle” was discussed in what was yet another urgent article. For decades hailed as a development paradox, the country’s socio-economic gains had coexisted with increasingly brittle politics. With the student uprising, that contradiction imploded.

Amid analysis came poetry:

Horses are shackled as long as they can run,

They are free when they can’t.

After many wars, dawn arrives like a consolation.

What is light for you, is a wound for the sun.

As Bangladesh has voted the Bangladesh Nationalist Party to power, those lines return with weight.