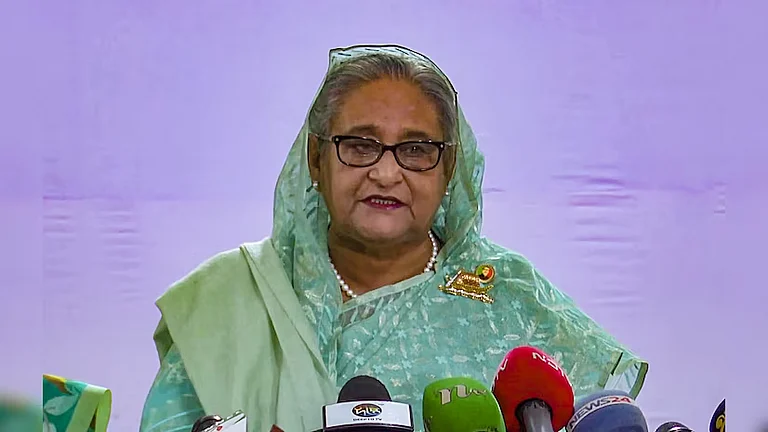

The evening sky hung low over Dhaka, heavy with the weight of impending change. The city was cloaked in a sombre mood, the kind that precedes a storm. It was the final evening of now former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year reign, a regime marked by escalating oppression. The air was thick with tension. At Dhaka’s Mirpur-10 roundabout area, an elevated metro station in the national capital, a massive crowd had gathered, their thousands of voices united in a single cry for freedom.

Among them stood Ikramul Haque Shazid, an accounting student from Dhaka’s government-run Jagannath University. His face was set with determination, his heart beating in rhythm with the chants that echoed through the streets.

The atmosphere was electric, charged with both hope and fear. As the crowd surged forward, their voices rose higher, challenging the regime. Then, a sharp crack pierced the evening air—a bullet fired into the throng. The world seemed to slow down as Shazid was struck. The bullet entered the back of his head, tore through his brain and exited through his eye. In an instant, the energy of the protest shifted from defiance to panic. Shazid crumpled to the ground, his blood mingling with the dust, as his life ebbed away and fellow protesters looked on in horror.

The chaos that followed was a blur—friends lifting Shazid’s limp body, a frantic rush to the hospital, blood-soaked hands and desperate prayers. In the harsh glare of the emergency room, faces were etched with worry. The doctors’ expressions were grim. The injuries were catastrophic and there was nothing more they could do. Shazid’s life hung by a thread and all that remained was the agonising wait.

The rapid infrastructure development and economic growth of Sheikh Hasina’s tenure, which had lifted millions out of poverty, were overshadowed by accusations of rampant corruption.

Meanwhile, across the nation, protests continued to intensify. The mounting pressure eventually forced Sheikh Hasina to concede. In the early hours of the following day, she fled the country, marking the end of her era. However, for Shazid, the victory was bittersweet since he was unconscious for ten days and suffering from brain damage. He passed away ten days later, on Wednesday, leaving his family devastated—not only by the loss of their loved one but also by the loss of their hope and support.

In Narayanganj, the sixth largest city in Bangladesh, another life was claimed in the same struggle. Abul Hasan Shojon, a 25-year-old private sector worker, joined the protests in face of the dangers involved. During a violent clash on August 5, ruling party activists shot him. As he fought for his life in a hospital bed, he learned that Sheikh Hasina had fled. With his last breath, he managed a smile and whispered, “Alhamdulillah.” He died the next day, leaving behind a world that had changed and a life that had ended too soon.

The stories of Shazid and Shojon mirror the broader struggle of a nation. The mood in Dhaka has shifted since those dark days. The streets, once filled with the sounds of protest and cries of the wounded, are quieter now, but echoes remain. The city breathes differently—there’s a sense of relief, hope and deep sorrow. The memory of those who fell in the fight for freedom lingers, a poignant reminder of the cost of change. Bangladesh has entered a new era, but the scars of the past remain etched into the fabric of the nation’s consciousness.

Over the past month-and-a-half, Dhaka transformed from a bustling metropolis into a battleground, where the fight for freedom and justice played out in vivid and harrowing scenes. The city’s streets, once filled with the everyday hum of life, became the epicentre of a fierce struggle marked by extraordinary acts of resistance, profound loss and ultimately, a collective outpouring of celebration.

The protests began in June 2024, starting as a small wave of discontent that quickly swelled into a nationwide mass uprising, shaking the very foundations of Sheikh Hasina’s regime. Initially, the atmosphere was a tense mix of fear and hope, with students gathering on university campuses to voice their concerns over the Supreme Court’s decision to reinstate a 56 per cent quota in civil service jobs. This decision reversed the government’s earlier reforms from 2018 and while the early protests were focused, they carried the weight of deep-seated frustrations.

In those initial days, the mood was one of cautious optimism. As night fell, protesters lit candles, their flickering flames casting a warm, hopeful glow over determined faces. The air was filled with the soft murmur of prayers and the steady rhythm of resistance chants, creating a poignant contrast between the peace they sought and the defiance they displayed.

The scars of the protests were visible throughout DHAKA—on the buildings, ON the people—but there was also a newfound energy and determination to shape a better future.

But this fragile hope was soon shattered. On July 15, the movement took a dark turn when the members of the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL)—a pro-government student body founded by the country’s first president, the late Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—armed with rods, sticks and revolvers, attacked students at Dhaka University. What had begun as a peaceful protest descended into chaos. The violence spread rapidly across the country, turning city streets into battlegrounds. The once-peaceful gatherings were now marked by the acrid smell of tear gas, the deafening crack of gunfire and the sight of protesters fleeing from charging police.

The following day, July 16, brought one of the most tragic and symbolic moments of the uprising. In Rangpur, at Begum Rokeya University, the police escalated their crackdown, firing tear gas and unleashing batons on crowds of students. Amid the chaos, protest coordinator Abu Sayed stood his ground, arms spread wide in a gesture of defiance. His bravery was met with brutality—police officers, positioned just 15 metres away, fired directly at him, killing him instantly. The video of his death spread like wildfire, becoming a powerful symbol of the state’s ruthlessness and igniting widespread outrage.

By July 18, the death toll had reached 48 and the violence showed no signs of abating. The government’s proposal for dialogue was rejected, as protesters, now mourning their dead, refused to negotiate under such dire circumstances. On July 19, the conflict reached a new peak with 86 protesters killed in a single day, marking the bloodiest chapter of the uprising. The streets, once filled with chants of hope, were now soaked in blood and the air hung heavy with grief and anger.

Even as the top court abolished most of the quotas on July 21, unrest continued to grow. What had begun as a student-led protest against specific grievances had now morphed into a broader movement fuelled by anger over government corruption and the regime’s heavy-handed response. The rapid infrastructure development and economic growth of Sheikh Hasina’s tenure, which had lifted millions out of poverty, were overshadowed by accusations of rampant corruption, particularly benefiting those close to her party, the Awami League. The public’s perception of this unchecked corruption only deepened their resolve to continue the fight.

In a desperate attempt to maintain control, Sheikh Hasina imposed a nationwide curfew, cut off internet access and labelled the protesters as “terrorists” bent on destabilising the nation. Yet, these measures did little to stem the tide of civil disobedience and the violence only escalated. Between July 16 and August 5—the day Sheikh Hasina ultimately stepped down and fled the country before the protesters reached her official palace—439 lives were lost.

The turning point came when news spread that Sheikh Hasina had fled the country. The atmosphere in Dhaka shifted from tension and fear to overwhelming jubilation. The streets, once filled with the sounds of protest and anguish, erupted in celebration. People danced, sang and embraced one another, their faces alight with the joy of victory. The oppressive weight that had hung over the city for so long was lifted, replaced by a collective sense of hope and renewal. The movement was about more than just toppling a regime—it was about reclaiming dignity and humanity in the face of oppression. Yet, even in this moment of triumph, there was a deep undercurrent of sorrow. The celebrations were tempered by the memories of those who had sacrificed their lives in the struggle.

In the days that followed, Dhaka began the process of rebuilding, both physically and emotionally. The scars of the protests were visible throughout the city—on the buildings, on the people—but there was also a newfound energy and determination to shape a better future. The nation now faces the challenge of rebuilding not only its political landscape but also the social fabric strained by years of oppression and conflict.

The departure of Hasina marked a pivotal moment for Bangladesh, ushering in 84-year-old Nobel Laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus as the leader of an interim government. While the celebrations reflected a desire for change, significant challenges lie ahead. Yunus inherits a country where political institutions have been eroded by corruption and autocratic rule. His leadership is expected to bring much-needed reforms, including transparent governance and the protection of civil liberties.

Economically, the disruptions caused by recent protests have left the nation in need of recovery. Yunus’s expertise in poverty alleviation could guide the country towards inclusive economic policies that address the needs of the marginalised. Socially, the interim government must heal divisions and promote unity across the diverse population.

Yet, there are reasons for cautious optimism. The movement that brought down Hasina was driven by a new generation of Bangladeshis—young, educated and deeply connected to global currents of thought. They are demanding more from their leaders and are unwilling to accept the status quo. This emerging generation has the potential to drive meaningful change, pushing for reforms that could finally address deep-rooted issues of inequality, corruption and injustice.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Rabiul Alam is a Dhaka-based journalist

(This appeared in the print as 'When Statues Fall')

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)