Bihar has a long history of industrialisation, with its sugar mills dating back to the late 18th century when the British East India Company was asked to meet the rising demand for sugar in Britain.

Besides sugar mills, Bihar was also home to many paper mills and Bhagalpur district was a major centre for the manufacture of silk textiles and garments.

Labour out-migration from Bihar is significantly high, which is attributed to poverty, inequality and high dependency on agriculture. The prime factor for labour migration is the backwardness of Bihar’s economy

From a distance, the abandoned Marhowrah sugar mill in south Bihar’s Saran district looks like an installation of abstract art. It wears the theme of desolation on its rust-covered pipes and long-defunct boilers left exposed to the elements by the wide cracks in the old walls that have collapsed at many places, letting the wilderness outside seep in and spread all over.

Chatting with customers at his paan and cigarette stall half a kilometre away, 75-year-old Awadesh Thakur seems quite disappointed with Amit Shah, who recently blamed “scarcity of land in Bihar” for the lack of big industries in the state. “As there is difficulty in acquiring land for big factories, we should bring those industries here that need less land,” the Union Home Minister had told a news channel on October 18 in Patna, the state capital 70 km away.

“How can he say this?” asks Thakur. “What Amit Shah is saying is wrong. If Bihar has no land, then how did the Britishers establish so many industries here? It is not about whether Bihar has enough land or not. It’s about the intention. They have no intention of setting up factories here.”

Pointing towards the old mill’s tall tower that still stands at its place, head held high, 36-year-old Ram Babu Ram, a customer at Thakur’s stall, remembers the days when this space was teeming with activity. “When the siren wailed, it could be heard from six or seven kilometres away. We could tell the time by the sound,” recalls Ram, who is now a migrant worker in Andhra Pradesh and has come home for a few days during the annual festive season. “If there were factories in my home district, then I would not have needed to move to another state in search of livelihood. Even if no factory here employed me, I could have still opened a small eatery near one and earned a decent living. At least I wouldn’t have had to leave home.”

Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar, too, has on several occasions argued that the state’s geographical location as a landlocked state with no sea ports makes it difficult for large industries to develop here. However, Bihar has a long history of industrialisation, with its sugar mills dating back to the late 18th century when the British East India Company was asked to meet the rising demand for sugar in Britain, which had seen a surge in consumption. In March 1792, a company officer in Bengal proposed that good-quality sugarcane could be cheaply cultivated in Bihar. In 1904, the first sugar mill was set up in Marhowrah by Kanpur Sugar Works to process the sugarcane grown in the farms to manufacture sugar mainly for the British market. Its campus, spread over 1,250 acres, was shared by three more factories—Saran Engineering, Morton confectionery and a liquor manufacturing unit. Morton’s chocolate became a household name in Bihar.

By the time British rule ended in 1947, 28 sugar mills were flourishing in the state. In 2023-24, according to Bihar government data, eight were still operating. The Marhowrah mill was shut down in 1998, locals say, when it employed around 1,200 workers. All of them suddenly found themselves without a job and among the burgeoning ranks of the unemployed. The closure came as a disaster for Thakur, who had joined the power generation unit of the sugar mill in 1980 as an apprentice before being offered a permanent position. “Jab mill chalu tha toh lagta tha ki yahan aathon pahar sona barasta hai (When the mill was running, it looked as if it was raining gold here all the time),” the former worker-turned-paan-stall-owner remembers. “All of us who worked here used to take pride in our work. Such was the reputation of the mill that many even quit jobs in the railways to join us.”

After the Marhowrah mill was closed, Thakur went to Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh to work in another sugar mill that paid 30 per cent lower wages in comparison. He couldn’t stick around and worked in different cities for six-seven years, but none of the various jobs brought him enough income to cover his family’s needs. “I failed to provide enough for the education of my two daughters and two sons,” rues Thakur, who eventually returned to Marhowrah and set up his paan stall in the vicinity of his former workplace—a reminder of better times.

Besides sugar mills, Bihar was also home to many paper mills and Bhagalpur district was a major centre for the manufacture of silk textiles and garments. In the early 1930s, the businessman Ramkrishna Dalmia started developing 3,000 acres of land in Shahabad (now in Rohtas district), on the banks of the Sone river, along the lines of the steel city Jamshedpur founded by Jamsetji Tata around 370 km to the southeast a few years earlier. This became the Dalmianagar industrial city, where Dalmia established several industrial units, schools, colleges, a railway line and an airport, making it one of the biggest townships of that era.

After 1970, however, the bad days began, with one factory closing down after another. On September 9, 1984, the smoke stopped billowing from the chimneys of the last factories that were shut down. Just a couple months earlier, as per records of July 8, 12,629 people, including officers and workers, worked in these units. All were left jobless with the closures. The company declared itself bankrupt and filed a petition in the Patna High Court to wind up its operations in Dalmianagar.

On May 22, 1986, the Patna High Court appointed a provisional liquidator to sell the company’s assets under their supervision and repay its outstanding loans. Legal battles dragged on for years. The state government tried to rescue the company a couple times, but without much success. “A few factories were reopened in 1986, then closed down again in 1990,” says Shiv Gandhi, a Dalmianagar resident who has been advocating for the revival of industries in the township. “It is sad that Nitish Kumar has never visited Dalmianagar in all his years as chief minister.”

During his tenure as railway minister, Lalu Prasad Yadav acquired land in Dalmianagar to build a railway factory on the site of a closed factory, but the project never took off. Once known as a township with all the necessary facilities, Dalmianagar today looks like a ghost city with its deserted and dilapidated structures.

“There is a historical background to Bihar’s backwardness in industrial development that is often ignored by economists and in popular discourse,” says Awanish Kumar, an associate professor at Azim Premji University in Bengaluru. “Industrial development in India took a specific and deliberate trajectory in the post-Independence period, while agriculture was treated like a bargain sector with the understanding that little to no investment could produce positive results. Eastern India, in general, and Bihar, in particular, already suffered from the feudal zamindari system and deep socio-economic inequality. With its neglect of agriculture, post-Independence policy worsened this situation. The current industrial deadlock in Bihar must be understood in this context.”

In other words, as the industrial policy in post-Independence India focused on heavy industry, it concentrated more investment in already advantaged areas, especially states with metropolitan centres. “Capital has a natural tendency towards spatial conglomeration,” explains Kumar. “The only way to bypass this is strong policy intervention, but that was lacking from Delhi. After the liberalisation of the economy in the 1990s, this process of uneven regional concentration of industry, in fact, turned even stronger.”

Not all the industrial units had shut down before Nitish became CM in 2005; many downed their shutters during his tenure. Mokama’s Bata factory, a leather manufacturing unit established five years before Independence across 14 acres, was shut down in 2014 and there has been no effort so far to reopen it. Besides this unit of the 250-year-old Czech-origin corporation, almost synonymous with footwear all over India until liberalisation, the town on the banks of the river Ganga was home to at least half a dozen factories, including a thread-making unit, a liquor-manufacturing unit of McDowell’s, and a railway wagon manufacture and maintenance unit. All these units, too, have shut down. The Bata motto—‘Uttam kharidiye, Bata kharidiye (Buy the best, buy Bata)’—is still legible despite the fading colour of the outside wall of the closed factory, serving as backdrop to a few goats grazing the grass that has grown on the main gate.

“We were paid our wages every Friday,” recalls 60-year-old Dev Kumar Paswan, one of the 700 contractual labourers who toiled at the Bata factory alongside an equal number of permanent workers, turning raw animal skin into leather. “On that day the hawkers would throng outside the factory gate, turning the place into a meena bazaar (mini market). The hen was laying golden eggs then, so to speak, but now we don’t have enough to eat.”

Paswan says 1,800 pieces of leather would be prepared every day and sent to footwear manufacturing units located at other places. “Raw skin even came from foreign countries and the polished leather was also exported to units abroad for making footwear,” he says. As people from the other castes would not touch raw skin, most of the workers were from the Scheduled Castes (SCs), mostly Chamar and Dusadh. The handful of managerial posts were held mostly by people from the elite castes.

“There was a day-long process of turning skin into leather in which various kinds of chemicals were used,” says Paswan. “It would smell very bad and the stink would linger on our bodies even after bathing. Even food smelt like rotten skin.” The company pays him Rs 1,000 every month as pension. “We are merely surviving. We heard the Narendra Modi government will increase our pension but it has not been done yet,” adds Paswan.

The closure of factories affects not just workers but the entire economy of the surrounding localities that sees a fall in people’s buying capacity as a result. Manoj Mahto, a 62-year-old who has been running a tea stall in front of the Bata factory for the past four decades, remembers the days when it was running to full capacity. “I needed 200 litres to milk daily to make the tea I used to sell,” Mahto recalls. It’s a Sunday morning but, unlike the old days, there is no crowd here. The coal-heated earthen stove at his stall is still burning but there is little warmth in his words. “When the factory closed, everything came to a standstill, and there is almost no income now,” he says. “Only a few people come here these days to just sit here and pass their time. Like them, I, too, come here mostly to pass my time instead of sitting idle at home. I am too old now to go out looking for any other work.”

Not long after the Bata factory, the Bharat Wagon and Engineering Company Limited, too, was shut down around 2017. Spread across 5,560 acres near the 90-year-old railway station in Mokama, the company used to employ 1,200 workers. “Wagons were made for freight trains here and old wagons were also repaired,” says 70-year-old Ramnath Saw, who lives in a temple near the closed factory. “There used to be two shifts and the whole place looked like a fairground teeming with people. We heard the unit was closed as it was running at a loss.”

Mokama was known as an industrial hub until the 1970s. “Then it became infamous for its bahubalis (strongmen),” says Saw. Many industrial units were shut down in the past 10 years. According to the Annual Survey of Industries, Bihar had 3,420 factories in 2013-14, which decreased to 3,307 in 2022-23. Only 2,782 are operational now. Though the state’s per capita income rose marginally from Rs 22,776 in 2013-14 to Rs 32,227 in 2023-24, it is still the lowest among all states.

“Bihar does have a very useful industry, one that produces cheap labour for places like Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Kochi and Chennai,” says Kumar, the associate professor, who believes industrialisation in Bihar is as much a political question as an economic one. Thakur, the paan-seller in Marhowrah, agrees with the logic. “If factories are set up in Bihar, then our people would not go to work in the factories in Gujarat, Mumbai, Delhi, Bengaluru… Those factories will have to be shut down. That is why factories are not set up here,” he says.

According to a research paper published in the Management Journal for Advanced Research in April, Bihar has the second-highest rate of out-of-state migration after Uttar Pradesh. “Labour out-migration from Bihar is significantly high, which is attributed to poverty, inequality and high dependency on agriculture. The prime factor for labour migration is the backwardness of Bihar’s economy,” the paper reads. Despite the grim data, though, Mahto is optimistic. “The roads are smooth, electricity supply is regular, and now I hope the government will establish small-scale industries here,” says the chaiwala in Mokama. Just then an e-rickshaw stops at his stall and the driver orders a kadak chai. Mahto pours milk into the tea pan and starts fanning the earthen stove under it to light the fire.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Umesh Kumar Ray is a Bihar-based independent journalist.

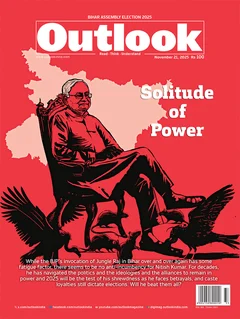

This story appeared in print as 'A Morass Of Lies, Deceit And Red Tape' in Outlook’s November 10 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.