It was May 2004. In the power corridors of Delhi, even the whispers were loud—‘Will the Congress be able to form the government? Will it be stable enough to survive for five years?’ The numbers were telling difficult stories and the most common words discussed in middle-class drawing rooms and on television channels were—‘coalition dharma’ and ‘coalition compulsion’.

Debunking exit poll predictions, the Sonia Gandhi-led Congress managed to get 145 seats, but the BJP was not too far behind with 138 seats. However, what made the difference was the numbers of the alliance partners. With the RJD, the DMK and the Left on its side, the Congress-led UPA was all set to form the government but with a caveat: the ‘common minimum programme’.

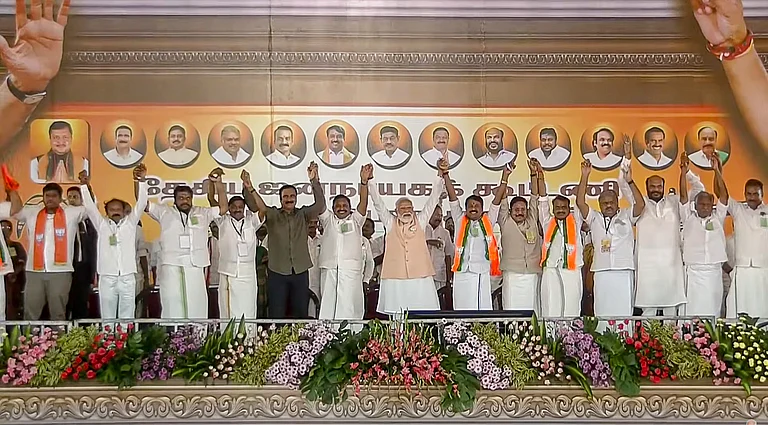

It has been twenty years since. But history has repeated itself. If not literally, at least symbolically, there are a few uncanny similarities. As in 2004, this time too, the exit polls failed to predict the numbers. Interestingly, the BJP is banking on parties like the JD(U) and the TDP—the same parties that Atal Bihari Vajpayee tried to woo in 2004—to form the government.

Though the NDA has been in power since 2004, its allies never had much of a voice or the capacity to influence policy decisions. And whenever there was any discontent over any policy issue, the partners had no option but to part ways.

The first ally that the BJP lost even before the party came to power with Modi as the PM was Nitish Kumar. This was the beginning of Kumar’s many flip-flops. He opposed Modi’s selection as the Prime Ministerial candidate. However, later, he continued jumping boats until recently when he surprised everyone by re-joining the NDA amid speculation that he could be the potential face of the INDIA bloc.

The ties between the BJP and its old partner in Punjab, the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), also snapped during the farmers’ protests. In September 2020, they parted ways. Political scientists believe SAD was compelled to snap ties with the BJP as it would have otherwise lost political relevance amid the farmers’ agitation that was getting more and more intense. The demands of SAD—including withdrawal of the controversial farm laws—were not heeded as they didn’t have the numbers to challenge the stability of the government. In 2024, talks between the SAD and the BJP did not materialise.

One of the silent allies of the BJP—the Biju Janata Dal (BJD)—suddenly became an eye-sore as Modi’s efforts to clinch a deal with Odisha CM Naveen Patnaik failed. In the early days of the campaign, while PM Modi was all praise for the second longest-serving CM of the country, within days, he took a U-turn. However, the BJD has been decimated in the Lok Sabha and Assembly elections after almost two decades, vacating the space for the BJP that is all set to form the government.

In a dominant party system, if you have the majority, you need not care about alliance partners, but if you need support to survive, listening to them becomes a compulsion.

The BJP-TDP ties have never been consistent. In 2014, although Chandrababu Naidu joined the Modi government, he left the alliance to fight independently just before the 2018 Andhra Pradesh Assembly elections. The point of contention was another policy decision of the Modi government—to not give Andhra Pradesh the special status that the party has been asking for since its bifurcation in 2014.

However, for Naidu, the biggest blow was his arrest in 2023 for his alleged involvement in the Skill Development Corporation scam. In November 2023, though he got permanent bail, speculation was ripe that he would be very cautious while treading the coalition path. Naidu also hasn’t forgotten that the central government sent the ED to raid his premises just after he left the BJP in 2018.

While criticising the Modi government for sending the ED to silence political adversaries, he had then said: “Whoever speaks against Narendra Modi faces IT and ED raids. We will not be afraid of all these acts. We will fight for justice until we achieve it. I am speaking on behalf of five crore people.” In the recent past, with one former and one current CM in jail for their alleged roles in different scams, it is difficult to believe that Naidu would take the risk to jump the boat, at least in the near future, say political analysts.

The BJP’s relations with its partners in the central government have mostly been controversial, but its history of running state governments with alliance partners also fails to instil much hope. In 2019, after the Haryana Assembly polls when the BJP didn’t have the required numbers to form the government, it was Dushyant Chautala’s Jannayak Janta Party (JJP) and his nine legislators who came to the rescue. They also made Chautala the Deputy CM.

But in 2024, during seat-sharing talks, Chautala became ‘too demanding’ for them, and they unanimously decided to sever their ties with the JJP. Interestingly, when the BJP severs ties, it not only keeps its flock together, it also gains when others bleed. A few MLAs of the JJP parted ways with Chautala and inched closer to the BJP. Notably, Chautala demanded two out of 10 seats in Haryana. Though the BJP won all the seats in 2019, in 2024, the INDIA bloc won five.

In Maharashtra, despite its pre-poll alliance with former Shiv Sena chief Uddhav Thackerey, the BJP couldn’t form the government. And after much drama over the years, when it staked a claim, the party did it at the cost of bleeding the Shiv Sena and the NCP. Against this backdrop, it is difficult to speculate how things would shape up in the coming days.

The history of the BJP’s relations with alliance partners in the last two tenures emboldened the perception that it is difficult for the party to take along alliance partners. Vajpayee’s two governments of 13 days and 13 months further feed into this perception. However, this time, with only 240 seats, 32 less than the singular majority, the party has to listen to the demands of its allies, believe political observers.

According to reports, the JD(U) has asked for a Common Minimum Programme and senior party leader K C Tyagi has already criticised the Agniveer scheme. In his election campaign, Rahul Gandhi made Agniveer one of the major electoral planks. On the other hand, it is expected that Naidu would demand special status for Andhra Pradesh the issues that pushed him to leave the alliance in 2018.

Therein lies the significance of maintaining ‘coalition dharma’. In a dominant party system, if you have the majority, you need not care about alliance partners, but if you need support to survive, listening to them becomes a compulsion.

In the recent past, one can recall the political turmoil of 2008 when the Left decided to withdraw its support from the UPA I government over the nuclear deal. Though the Manmohan Singh government was saved and it gradually led to the further decimation of the Left, the Gandhis had to rush to take then SP supremo Mulayam Singh Yadav on board. The Congress and the SP rarely clicked in the past. But Yadav said former President APJ Abdul Kalam convinced him the nuclear deal was good for the country and hence he decided to save the government.

The Congress, nonetheless, had to activate all its machinery to save the government, but in 2018, when the NDA faced a no-confidence motion, it was a cakewalk for them. The BJP won 282 seats in 2014 and 303 in 2019—enough to dodge the ‘coalition compulsion’.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

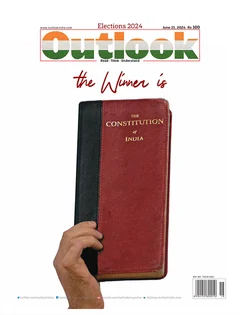

But will it be the same for the party in the coming days? Will the party be able to maintain the coalition dharma? Only time will tell.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Coalition Dharma')