Books are reaching people via trucks, horses, camel carts, and public spaces.

Villages and cities are turning everyday spots into reading hubs.

These efforts build community, preserve culture, and spark joy in reading.

My son and I spent five hours at the Madurai passport office lounge last year for his passport renewal. What made those hours less bleak was that the waiting lounge had a well-stocked library. Turns out the regional passport office used to stock applications and documents in this space and when they went paperless, the Regional Passport Officer S Maniswar Raja decided to turn it into a library in 2017. The library has over 3000 books and seating, and it can be used by visitors and students on producing their ID cards. We picked a book each, dived right in, and then the wait didn’t seem so bleak. I wondered why other passport offices in India, visa processing centres, hospitals, hotels hadn’t thought of it.

Akshaya Bahibala of Walking Book Fairs had the same thought. “Why don’t we see books in all places, like we see chips, biscuits and cold drinks? Books are products too, and they need to be advertised, displayed everywhere,” he says. With this in mind, he co-founded Walking Bookfairs along with Satabdi Mishra in 2014, taking books in backpacks to public spaces in Orissa, displaying them, inviting conversations around them. Soon he bought a Maruti Omni which was a defunct ambulance and aided by his bookmobile, started the “Read More, Orissa” project, which soon expanded to the “Read More, India” project in 2015 with a bigger truck and more books. The Traveling Bookshop has already clocked in 35000 km. Bahibala now has two bookstores in Orissa, and has helped books travel in more ways than one.

In a unique Travel Writing Festival hosted by Walking Book Fairs in 2024, an entire coach of 63 people, travelled from Bhubaneshwar to Puri, discussed travel books, had travel-writing sessions on the train, followed by more sessions on the beach. Next year, the festival will be on a bus from Bhubaneshwar to Puri, stopping at Khandagiri and Dhaulagiri and integrated with local food and cultural experiences.

In 2017, the Maharashtra Government helped transform Bhilar, a village in Satara known for its strawberry fields, into India’s first Village of Books. This Pustakache Gaav is inspired by ‘Hay on Wye’, a Welsh town in the United Kingdom, known for its book stores and literature festivals. Many houses in Bhilar were already offering homestays under a MTDC (Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation) project to help rural families benefit from tourism. The state language department equipped these houses with glass-fronted cupboards to store books. Each of the 25 locations in the village has at least 400 books, mainly in Marathi. Visitors can walk in, browse through books, even lounge around reading them.

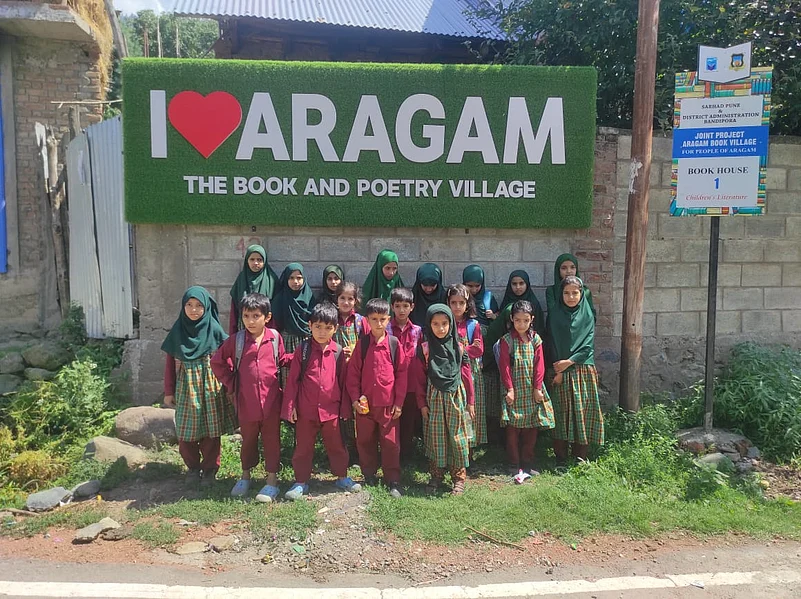

Sarhad, a Pune-based NGO established in 1997 took its cue from here and nurtured Aragam, a book village in Kashmir in collaboration with the Jammu and Kashmir Government. Sirajuddin Khan, a Kashmiri local who runs the project says, “Until 2022, this village didn’t see any tourism although it is home to the Wular lake (the largest freshwater lake) and only an hour away from Srinagar. Since Aragam has opened, we have had 500-600 tourists.” 15 local homes have already been transformed into libraries, showcasing Kashmiri literature and culture, along with Indian and international literature.15 more bookhouses are in progress, and there are also plans to start a literature festival in the future and explore a book-village in the north east.

Sarhad has also been mentoring Beed village in Maharashtra, notorious for its high crime rate. “Wherever there is violence, we try to start a reading movement. When we make readers, we also make fewer criminals,” says Nahar, who started a program called Beed Vachtay (Beed Reads) where books are taken to schools and homes for people to read. Pune resident Leshpal Javalge who became famous for saving a woman from a koyta (machete) attack in Pune in 2023 is the champion of this movement in Beed.

Further south, a school teacher in Kerala, V. Vijesh transformed Perumkulam, a village in Kerala with a population of around 4000 people into Pusthaka Gramam (Book Village) in 2019. Perumkulam’s transformation involved, among other things, placing 10 pusthaka koodu (house-shaped glass bookcases), across different spots in the village, modelled on the US-Based Little Free Library that Perumkulam is registered with. These community bookcases bring villagers together and foster a culture of reading and sharing literature. Each koodu has 30-50 books, mostly children’s literature which kids can borrow.

“It is good that people are trying different things, based on what drives or motivates them,” says Thejaswi Shivanand, who is associated with supporting the work of libraries and library educators across India as an advisor and facilitator. “The work of libraries is always long term, but overall they tend to look at a more inclusive community, accepting worlds, bringing people together rather than keeping them separate, which is what tends to happen in a divisive society,” he adds.

But what does it mean to be a space for such a coming together, or even trying? Some community libraries have been started by people who want children of different backgrounds to come together. Others, who are more social-justice oriented will have a different approach, but every library opens up conversations that require thinking and reflection.

But what else can a library be? NALC, a government initiative in Arunachal Pradesh set out to define a library more as a learning space. Brainchild of the Changlang District Magistrate, Sunny K Singh, NALC is a flexible, state-of-the-art, futuristic, leisure learning space-cum-library in the Miao subdivision to enable people from all age groups to learn and grow.

In Meghalaya, The Sauramandala Foundation through its Forgotten Folklore Project gathered and converted several community stories into children’s books, thereby documenting a lot of oral history to preserve Meghalaya’s rich cultural heritage. The Ayang Trust is trying to do a similar thing in Majuli ( a riverine island in the Brahmaputra), documenting oral histories and stories in a printed form. In both cases, a library is doing the work of a cultural archivist.

In the rural districts of Madhya Pradesh - Raisen, Betul and Mandla - The Library and Reading Initiative (LARI) has been at the forefront of Eklavya’s work since the 1990s, both through school and community libraries. Tultul Biswas, Director of the Foundation wondered what if the agency of children who benefit from the library was at the centre of it? “After all, a library is a very different space from a school, in that you have a free space to choose. And getting that front seat is such an important aspect of learning,” she says. “What if this aspect was also in the functioning of the library, not just the content?”

And thus was born the Chakmak Club, spaces owned, anchored and managed by groups of children. Around 20-40 kids from each village frequent the library, of which 6-8 take the responsibility of running the space. Sometimes books are used as manuscripts to create plays, at other times, to run science experiments.

In the Sunderbans, the Mobile Pathshala is a series of libraries that actually took books across the delta. In Cuddalore, Banupriya Jagadeesan goes from school to school doing read-alouds as a part of the Free Library Network. She also runs Reading Space, Belongg Library’s Cuddalore chapter, from her own home where she houses about 400 books. Belongg Library is a network of cultural and literary spaces across India that seeks to promote diversity and inclusion and so, besides offering children’s books, Banupriya also offers books that bridge gaps between communities and raise awareness on how we can create a more diverse and inclusive world.

In Uttarakhand's Kumaon, a unique 'Ghoda Library' trots up to remote villages, loaded with books for children. This initiative was started by Shubham Badhani, who wanted to make books accessible to children in remote areas. In fact, many parents volunteered their horses as 'four-legged librarians', making the initiative sustainable. The Ghoda Library is now being adopted by many other villages in the district of Nainital.

In rural Jodhpur, as an initiative of the education department along with the NGO Room To Read, a camel cart regularly trots up village to village to serve around 1500 books to kids.

The Free Libraries Network (FLN) is a platform anchored by The Community Library Project (TCLP) in Delhi to connect free libraries across India so that they can support one another, enhance thinking about library practices, and become a resource-sharing hub. Currently it is an online network of over two hundred librarians, educators, and enthusiasts working across the country in different spaces and contexts.

“For a long time, most of India has been denied access to books and reading. NGO libraries have the right intent but are strapped for resources. Space is a big issue. Schools have the space but have demands on ensuring outcomes. Community libraries are doing their best but are always beholden to patronage and donations. In this environment, any library is good news,” says Shivanand.

For now, the library movement is in the hands of a handful of enthusiasts, and it will take a while before the state begins to play a significant role or any role. Anything other than ‘education’ is not a priority at the state level. Other than Karnataka, where Gram Panchayat libraries are getting a fillip from the state, mostly as a source of information for state-run schemes, most villages in India don’t have access to books, forget bookshops or libraries. People are afraid to open bookshops and libraries, because the logistics of shelving, protecting books requires deep pockets. “May be the state and the municipality should protect and subsidize spaces for libraries and bookshops,” says Bahibala. “Books should be everywhere: every university should have a bookshop, every hospital, every hotel, every consulate, every airport and train station should have books. If we can have a Reliance in a small town, why not book shops and libraries?” he asks.

In the end, any library is a fodder for the mind, a sanctuary for thought. Picking up a book and immersing in its pages sometimes may be the oxygenation we need in the time of brainrot. “The hand-held devices seem to have bypassed the need for knowledge and stories,” says Shivanand. Libraries can change that.