Summary of this article

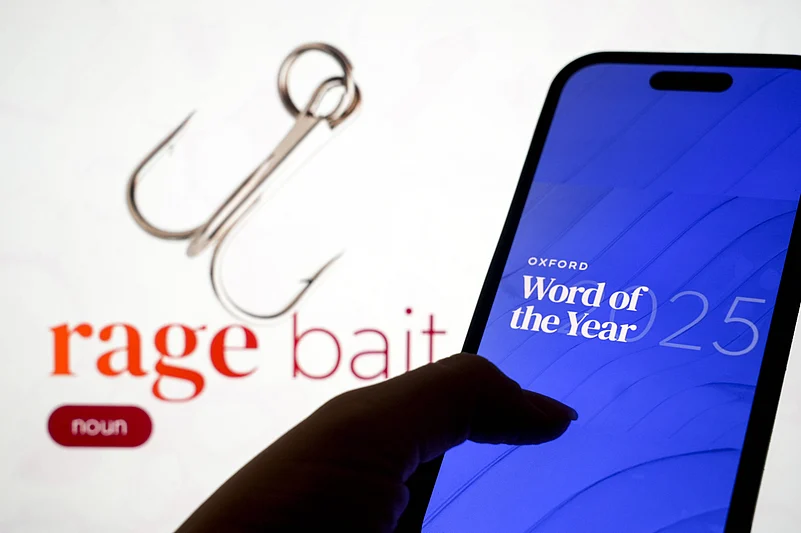

Every year, the folks at Oxford choose a ‘Word of the Year’, which is essentially an expression that has grabbed a significant amount of attention in the last 12 months.

It usually acts as a linguistic mirror, a documentation of social history through language, and reflects significant cultural shifts.

The Oxford Word of the Year in 2025 is ‘rage-bait’, and clearly it hasn’t gone down well and has actually induced rage in certain circles. It is

The Oxford Word of the Year in 2025 is ‘rage-bait’, and clearly it hasn’t gone down well and has actually induced rage in certain circles. It is problematic because rage bait in essence is intentional and targeted, unlike ‘brainrot’ ; it relies on exaggeration and falsehoods to provoke reactions, blurring the lines between fact and inflammatory opinion, and worse, turning anger into a commodity for ad revenue and traffic. Rage-bait was defined as “online content deliberately designed to elicit anger or outrage by being frustrating, provocative, or offensive, typically posted in order to increase traffic to or engagement with a particular web page or social media content”.

Women for instance, have often been the target in rage-bait scenarios, with misogynistic content being at an all time high, and now the internet even rewards it. In a sense, it is the monetisation of anger, with social media algorithms often rewarding provocative content, creating a feedback loop that amplifies rage. Rage baiting can happen in many forms, ranging from an online post about a controversial topic written in a polarising manner, or a video that exaggerates information and deliberately lacks nuance.

Every year, the folks at Oxford choose a ‘Word of the Year’, which is essentially an expression that has grabbed a significant amount of attention in the last 12 months and has become an important part of the public discourse. It usually acts as a linguistic mirror, a documentation of social history through language, and reflects significant cultural shifts, collective moods and major events (such as the pandemic in 2020). This is not random at all, but arrived at after considerable debate by experts on various candidates before they decide on one that reflects the ethos, mood or preoccupations of a particular year.

Oxford 2016-2025: A walk down the past decade through Oxford

2016: post-truth

In November 2016, Oxford University Press (OUP) declared post‑truth its Word of the Year, signaling that something fundamental had shifted in public life. It was a year rocked by the U.K.’s Brexit referendum and the U.S. election of 2016. The rise of ‘post-truth’ usage (around 2000% compared to the previous year) wasn’t just about a quirky new word - it was a linguistic testament to a political tectonic shift. The term became a catch-all for what many felt was a disorienting moment in civic discourse.

2017: youthquake

In 2017, the focus shifted to ‘youthquake’ - a term coined in the 1960s by fashion editor Diana Vreeland to describe a generation-led cultural revolution. It was in recognition of a collective energy, not led by fashion or pop culture, but a renewed sense of political urgency among younger generations: rising voter turnout among youth, youth-driven activism, and a palpable sense that young people were rewriting social rules. Youthquake, in a sense was a demographic wave that seemed to promise change.

2018: toxic

The choice of the word toxic was less about chemistry: in conversations about environmental pollution, waste, contaminated air; but more metaphoric: toxic relationships, toxic culture, toxic masculinity, and included social and political toxicity: cultural practices, institutional decay, abusive ecosystems. ‘Toxic’ was a lens, a mood, a shared worry about what was poisoning public and private life alike.

2019: climate emergency

The two-word phrase ‘climate emergency’ was a clear signal of global concern around environmental crisis and climate change. That choice marked a shift from emotional toxicity to existential risk at a planetary scale. It had become increasingly clear that climate change was no longer background chatter, but immediate and urgent - a crisis demanding action, reflection, and rethinking of systems.

2020: no single word

The year 2020 broke the pattern and OUP released a broader report, calling 2020 a “year of unprecedented change” - a nod to the global pandemic, widespread social disruption, and the multiplicity of new, urgent concepts and realities, 2020 was too complex, too chaotic, too multifaceted to encapsulate with just one snapshot.

2021: vax

With vaccines rolling out and people lining up for them in panic – a global health discourse dominating life, OUP declared vax the Word of the Year, since vaccination became became a part of daily conversation. It also signified how language adapts quickly in times of crisis and represented hope and fear in equal measure.

2022 – goblin mode

Post pandemic, as the world struggled to return to ‘normal’, a large section of humanity rejected various performative norms and chose unapologetic, self-indulgent, often lazy behaviour. Goblin mode captured a mood of fatigue, defiance, and casual honesty - after all the upheavals, many just wanted to let go or just be. It was also the year when OUP allowed public voting for its Word of the Year for the first time.

2023 – rizz

2023 was all about Gen-Z and the word of the year ‘rizz’ was a slang - implying charm or charisma, especially used in the context of romantic or social attraction. With this choice, Oxford leaned fully into a new era of digital-first, youth-driven vocabulary. ‘Rizz’ is playful, fluid, ephemeral and reflects how language evolves in online spaces, and how younger generations use it to signal identity, attitude, belonging.

2024 – brain rot

This was an apocalyptic year for the brain with the continuing post-pandemic deterioration of mental and intellectual state at an all-time high due to overconsumption of trivial or low-value online content (memes, social media, short-form video). It was a year self-awareness about digital life and its impact, especially among younger users, and the price they had to pay in terms of mental health and attention economy. Brain rot was the next pandemic.

Over the last decade, the progression from “post-truth” to “rage bait” tells a story of uncertainty, activism, crises - but also of adaptation, introspection, and change. There has been a recurring focus on emotion and attention. Ultimately, the language we use says a lot about the state of our society, which is why the Oxford Word of the Year isn’t just a fun “buzzword of the year” game, rather a mirror - a snapshot showing which ideas, anxieties, hopes and fears demanded attention in a given year.