Kannanari sees fiction as truth-telling, with stories shaped by long-maturing ideas, disciplined craft, and a focus on language rather than improvisation.

His novels intertwine character and society, exploring caste, colourism, moral contradiction, and the uneasy truths people avoid about themselves.

He treats writing as a full-time vocation, values English for expressive freedom, and uses Kerala as a lens for universal Indian social realities.

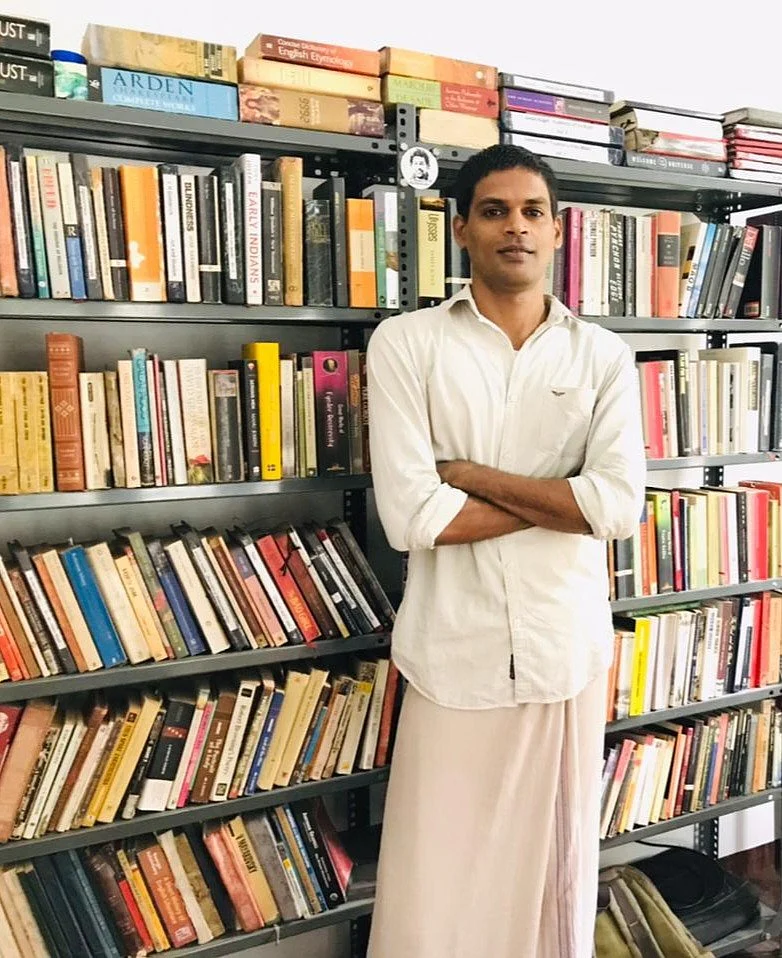

His critically acclaimed debut novel, Chronicle of an Hour and a Half (2024), took the literary world by storm, made it to the final shortlist for the JCB Prize for Literature and won the prestigious Crossword Book Award 2024 and the Atta Galatta Bangalore Literature Festival Book Prize 2024 in the Fiction category. His second novel, The Menon Investigation, about a police procedural as a lens for society, has just been published and is gathering accolades. Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari lives in a small town called Areekode in Kerala and is currently working on his third novel.

An astute observer of the human nature, society and religion, he believes that fiction is a medium to tell the truth. Excerpts from the interview with Lalita Iyer:

Looking back at your debut (Chronicle of an Hour and a Half) and now this second novel: what changes did you make to your process (in terms of research, plotting, character‐work) specifically for The Menon Investigation?

The ideas for my novels, whether it is Chronicle of an Hour and a Half or The Menon Investigation or the one I am currently working on, have been with me for a long time. So, when I sit down to write, the idea would have already matured in me well enough in terms of the plot, the structure and the characters and the business of writing essentially comes down to the pursuit of the appropriate language with which to limn it. Of course, it doesn’t mean that I am in possession of each and every detail in the novel before I set out to write. One certainly finds out things as one goes along. But, as E.L. Doctorow pointed out, writing a novel is like driving home at night. You can only see as far as the headlights, but this way you reach home. This certainly means that one knows the starting point, the way, and the destination. In other words it’s very unlikely that I will feel stuck midway, or ask what Michelangelo asked his Moses, Perche de parle?—why don’t you speak?

Caste and colourism are central to The Menon Investigation, like you call caste the nation’s ‘original sin”. How did you balance the story-telling and character-building with the social commentary?

I don’t call caste the nation’s original sin. One of the characters in the novel does. I don’t think it is right critical practice to attribute the opinion of a character in a novel to the novelist regardless of whether the author concurs with that opinion or not.

I don’t think I make any special effort to marry the story-telling with social commentary. However, since a novel is not created ex nihilo, that is to say since a novel is set in a specific society and aspires towards a kind of mimesis, the story and the characters are bound to be wound together in a game of mutually reinforcing marriage which necessarily yields social commentary.

A book of fiction is a lie that is true and caste and colourism are central to our truth, both in progressives and conservatives, both in men and women. I am very well aware of the common proclivity to reject the centrality of caste and skin colour consciousness in the choices people make—while falling in love, let’s say—as generalisation, a base impulse to insulate oneself as exceptional, and my books will fail to speak to them. My books are for those who aren’t afraid to gaze into the mirror with non-narcissistic eyes. I am certain it doesn’t always take a Vijay Menon to stop an inter-caste marriage between Savarna and Avarna frankly because such situations are rare. One just have to review the free-choices one has made in life so far by taking a casual glance at one’s dating history to recognize that there is a method to our accidents so far as falling in love is concerned, that we conform to the rules of caste far more than we would like to acknowledge. However, even though I think that human being is self-deceptive even on the last rung of consciousness, that it tells itself stories of denial to sleep, that it is generous to itself and harsh on others, I also believe that there is deep within the rock of our self an awareness that has a capacity to weaken what we preach who we are and my works aspire to be helpful.

Both your novels are set in Kerala. What does the Kerala setting allow you to do that a more generic Indian setting wouldn't?

Kerala doesn’t have a uniqueness that departs significantly from the general Indian society. This is not to say that Kerala isn’t unique—there are plenty of reasons to believe that it is unique in many ways—but I think our commonalities in terms of the social realities are stronger than our differences.

In your second novel, your protagonist, IG Vijay Menon, is both insider (of the system) and outsider (in terms of his skin colour, his caste background, his personal anxieties). How did you work with his internal contradictions, and in what ways did his flaws carry the weight of the narrative?

What essentially a novel does is create a set of individual consciousnesses that are distinct from one another and project a complex whole. The overarching consciousness in this novel is Menon’s, who is both a victim and a perpetrator, or at least a potential perpetrator, someone whose flaws flows from both within and without, and everybody else is designed to subserve his complexity.

I have always believed that one of the chief responsibilities of novel as an art is to practise the radical sensitivity of humanising the perpetrators and The Menon Investigation was conceived with that particular intent.

The idea for this novel was triggered by a sentence that I’d read in Running Dog, one of the early works of Don DeLillo which goes like this: ‘At the end of all our long and obsessive searches, in her view, was some vital deficiency on the part of the individual in pursuit.’ By this he meant that there is something within us that keeps us from reaching our goals. While this sentence doesn’t necessarily inform the philosophy behind the novel itself, I was reminded of so many other related ideas I’d read in other books. I remembered, for example, Carl Jung who, in his Psychology and Religion: West and East, said, ‘The acceptance of oneself is the essence of the whole moral problem and the epitome of a whole outlook on life. That I feed the hungry, that I forgive an insult, that I love my enemy in the name of Christ—all these are undoubtedly great virtues...But what if I should discover that the least amongst them all, the poorest of all beggars, the most impudent of all offenders, yea the very fiend himself—that these are within me, and that I myself stand in need of the alms of own kindness, that I myself am the enemy who must be loved—what then?’ I remembered Schopenhauer who, in his Parerga and Paralipomena, said, ‘The world is hell and men on the one hand are tormented souls and on the other the devils in it.’ I remembered Blaise Pascal’s words in his Pensées, ‘The embarrassment wherein he finds himself produces in him the most unjust and criminal passions imaginable, for he conceives a mortal hatred against that truth which blames him and convinces him of his faults.’ I happened to remember William Gaddis who opened his A Frolic of His Own with the famous words, ‘Justice? You get justice in the next world, in this world you have the law.’ I remembered lots of other stuff but, most important, I remembered the words of Prophet Nathan in 2 Samuel in the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible, where he offers King David a scenario by way of a parable and asks him to pronounce judgement upon the sinner in that particular story. King David says I will punish him with death and Nathan, in a stunning response which both alarms and embarrasses the king, says that ‘You are that man,’ words which serve as the epigraph to the book. Now this maxim, to call it that, may not be a literal truth. But its near-truthness lends a radical access to our interiority. The novel suggests that human capacity to be authentic is deeply strained by diverse social and psychological factors, that a serious investigation into the self most likely would leave us staring into the mirror. To this end the novel supposes that the Varna system is intact, that there is no serious dent to the notions of bodily pollution and purity even among those who consider themselves emancipated, and it instrumentalises stereotypes to achieve this.

You’ve mentioned elsewhere that writing is your job, not a romantic calling. How did you arrive at this stance, and how does it shape your daily routine or mindset as a novelist?

This is true. This is a job. I intend to earn my livelihood by writing novels. I also don’t read novelists who have other means of earning their livelihood just as I don’t buy my furniture from part time carpenters or umbrellas from part time umbrella makers. It doesn’t mean that part time novelists don’t produce great works, sometimes they do, but this is rare. If you are a serious novelist, I am certain you won’t have time to do anything else. To answer the second part of your question, well, I am a very disciplined writer who sleeps early and wakes early. This has been my life for a very long time. I get very disoriented if I don’t do my daily hours. It is my routine that gives me my novels.

How do you view of the role of language (English, Malayalam, etc.) in expressing the cultural and emotional textures of your setting?

Every language in the world is more or less well developed in terms of resources. However, since a language takes character out of its speakers, and since our sub-continental culture is deeply governed by inhibitions of all sorts, I would say English allows me to speak as freely as I want to.