Mistaken for a boy through her early teens, Kashvee Gautam built her game in gully cricket and male-dominated grounds, fighting social norms, lack of infrastructure and identity policing to survive in the sport.

From a government school ground in Chandigarh to becoming the most expensive player at the WPL auction, Gautam’s rise mirrors the broader transformation of women’s cricket—fuelled by the WPL, equal match fees and growing visibility.

Two major injuries threatened to derail her career, but Gautam returned each time with impact performances, inspiring a new generation of girls who now see cricket not as an exception, but as a future.

A pixie haircut. Broad shoulders. A loose T-shirt and a confidence in her movements that made her seem older than 13. When she walked into the government school ground in Sector 32, Chandigarh, even seasoned coaches didn’t question it. They assumed she was another boy looking for a net session.

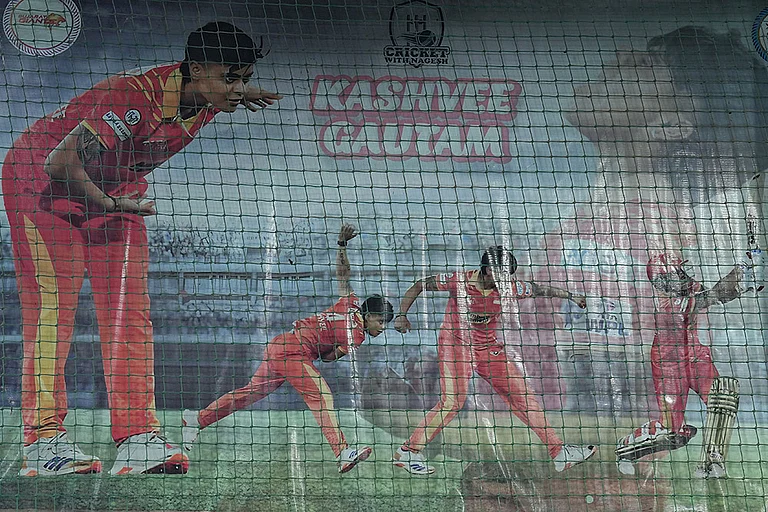

“I also thought she was a boy initially,” recalls cricket coach Nagesh Gupta, who would go on to shape her cricketing life. “She still looks like one sometimes. But when I made her bowl, I knew immediately that this kid is different. Natural action. Smooth.”

That ‘boy’ was Kashvee Gautam. For years, she had been hiding in plain sight, playing gully cricket with boys who were unaware that she was a girl, waking up before dawn to play in parks, cycling through lanes to avoid being seen in school uniforms she didn’t feel comfortable in, quietly building the foundation of a career that would take her to the Women’s Premier League, the Indian team. And beyond.

For decades, women’s cricket in India stayed in the shadows, seen as a ‘man’s game’, underfunded, poorly supported, with players earning just Rs 1,000 per match even during the 2005 World Cup. Change began after the women’s association merged with the BCCI in 2006, but real momentum came much later with equal match fees in 2022 and the launch of the WPL in 2023, laying the groundwork for greater visibility and professional support.

When she started out, Gautam says, she used to wonder if a Women’s IPL would ever happen. Now when she plays, she notes that “the crowd is so loud that I sometimes have to cover my ears. Even in Tier-2 cities like Vadodara, stadiums are full.”

The Indian Women’s team’s recent win in the ICC World Cup resulted in accelerated investment, recognition and even parity in the sport, giving the team not just historic rewards but also widespread public acclaim.

Growing up in Chandigarh, Gautam gravitated toward sport—from skating, volleyball to athletics—since childhood.

Her father, who had once wanted to be a cricketer himself, often took 10-year-old to a playground in the nearby government school.

“I used to wake up at 5 in the morning to play,” she says. “Then I’d return from school and go straight back to playing in the streets or the park.”

The boys she used to play with in the streets thought her name was ‘Kashu’, a nickname given to her by her family and peers. “For a long time, they actually believed I was a boy,” Gautam says, adding that it was only when her name appeared in the newspapers for being selected for the State Under-19 that her childhood peers found out her real name was ‘Kashvee’.

What now feels like a fond memory was her only way to survive in the game back then.

In 2023, Gautam became the most expensive player at the WPL auction, picked by Gujarat Giants. She was 20 and that moment was life-changing. Launched in March 2023, the Women’s Premier League finally gave women cricketers a professional platform—15 years after the men’s IPL—offering faster pathways to the national team and pay running into lakhs and crores.

“The bid jumped from Rs 10 lakh to two crore in minutes. We watched in disbelief,” recalls Gautam’s father.

However, the opportunity slipped away for her. Days after the auction, she fractured her leg, leaving her unfit to play any matches that season. In 2024, she returned and made her presence impossible to ignore, finishing as the joint highest Indian wicket-taker alongside Shikha Pandey, another Indian cricketer.

Then came a second injury in May 2025, just after she was selected for the Indian team for a tri-series in Sri Lanka. “Those two years were the hardest emotionally,” Gautam admits.

She got fit just before the next Women’s Premier League and once again, made an impact. Once again, the selectors took note.

This time, she stayed on the field.

India has only a few cricket academies dedicated solely to women currently. Most offer women’s coaching as an add-on, often without residential facilities, making access and safety a challenge. The Himachal Pradesh Cricket Academy in Dharamshala and the Female Cricket Academy in Mumbai are rare exceptions.

For Gautam too, there were few doors open. Her journey changed through an almost accidental encounter.

Former Ranji player Sanjay Dhull first noticed Gautam outside a cycle repair shop. Dhull assumed she was a boy, only to later find out her gender when she asked him if there was a training centre for girls. The next day, Dhull narrated the incident to coach Gupta and suggested that he train her. Gautam began training professionally under Gupta in 2016, when she was only 13. The ground, a government school facility, was overwhelmingly male, with boys outnumbering girls nearly 15 to one. She was also Gupta’s first female student.

“She had that swagger from the start,” Gupta says. “Confidence. A solid build. She was 13, but looked 15 or 16.”

And she bowled fast.

“She wanted to beat everyone, boys included. And she was ready to put in extra hard yards for it,” he says.

Practice began at dawn and often stretched late into the morning, resuming again in the evenings. For Gautam, along with another prodigy, Amanjot Kaur, who went on to be part of the Indian women’s squad that won the 2025 World Cup, even the change in seasons never mattered.

“Practice was at 5.30 am, but they arrived by 5 am. Seeing that made me start coming early too,” Gupta said.

***

As Gautam navigated the policing by relatives and the lack of choice in her clothing, her parents continued to be her support system.

“We never forced her to change,” her mother says. “She did not want to wear clothes traditionally meant for girls.”

It was only in Class 11, after repeated requests to the school principal, that Gautam was finally allowed to wear track pants instead of the prescribed uniform. By then, cricket had already begun reshaping everything. Her confidence. Her sense of self.

Gautam played state cricket for Punjab at 14, making an immediate impression. But her defining domestic moment came after Chandigarh received BCCI affiliation in 2019. She switched states and, almost instantly, made history as she took 10 wickets in a single innings in a BCCI Under-19 match against Arunachal Pradesh, a feat no Indian woman had achieved before, earning her selection in the Trailblazers team for the Women’s T20 Challenge in 2020, putting her on the national radar.

Gautam’s evolution has not been limited to bowling. Under Gupta’s insistence, she worked on her batting, often reluctantly at first. It paid off spectacularly when she scored a domestic hundred batting at No. 9 in the Challenger Trophy for North Zone.

Today, girls from across India, including Kashmir, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and several other states arrive at the academy asking if this is where Gautam used to train.

“Now parents want their daughters to pursue a career in cricket, which was not the case earlier,” he says adding that he often receives calls to confirm if he is the one who trained Gautam.

“I want to bowl like Kashvee,” says eight-year-old Sanyuri, who comes regularly to train at the same academy.

While the perception about cricket being a male sport still persists in some parts of India, Gautam believes that women cricketers have proven the world wrong over the years.

Mrinalini Dhyani is a senior correspondent at Outlook. She covers governance, health, gender and conflict, with a strong emphasis on lived realities behind policy debates

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled No More A Gentleman's Game dated February 11, 2026 which explores the rise of women's cricket in India, and the stories of numerous women who defeated all odds to make a mark in what has always been a man's ballgame