Jasia Akhtar grew up in conflict-hit South Kashmir with little access to facilities, facing social resistance and militant threats, yet persisted in pursuing cricket with the support of her father.

Seeking better opportunities, she moved to Amritsar in 2013, went on to play extensively in domestic cricket, became the first woman cricketer from J&K to be selected for a national camp, and later made history by entering the Women’s Premier League.

Now captain of the J&K senior women’s team, Akhtar has scored over 5,000 career runs and remains a trailblazer for women’s cricket in underrepresented regions.

In the early 1990s, young Jasia Akhtar, who lived in Brari Pora village in South Kashmir’s Shopian district, would watch young boys play cricket in the fields. The bats were mostly made of logs; the balls were often tennis balls or plastic ones. There were no grounds or pitches. The village, which sat in the lap of the Pir Panjal mountain range, was nestled deep in apple orchards. People, who mostly worked in these orchards, struggled financially. Militancy was on the rise, too. Amid the daily struggles and threats, cricket emerged as an aspiration. The matches broadcast on television were an instant hit. A young Sachin Tendulkar was a hero for many, including Akhtar.

It was fascinating for her to see her cousin pad up and bat. When she expressed her desire to play cricket with the other boys, her father, a daily wager who barely earned Rs 200-300, made her a bat with local wood. But he had to be cautious. A girl playing cricket, that too with boys, was an aberration in Kashmir. But he let her play because she was obsessed with her bat and ball. She didn’t have fancy shoes or clothes, and often had no playmates to practise with as there were no separate fields or academies for women, but Akhtar was focussed. As her talent flourished, year after year, and she started competing professionally, villagers started frowning and militant threats increased.

One day, when she was around 17, militants barged into her home. They threatened the family and told Akhtar to stop playing for the country. The scared family had to put a halt to her cricketing dream for a couple of years.

Her journey from then to now—Akhtar is the only player from J&K to make it to the Women’s Premier League (WPL), is now the captain of the J&K senior women’s cricket team, and, at 37, is a senior-level batter and bowler, with a long list of incredible stats—is what dreams are made of, especially those that are threatened and throttled, particularly in underrepresented areas.

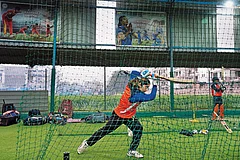

Despite the break in her cricketing journey, Akhtar persisted. In 2013, at 25, Akhtar moved to Amritsar, seeking better infrastructure and training opportunities, which were lacking in Kashmir. It was also an escape from persistent shutdowns, curfews and militant threats. From the 2014/15 season through 2020/21, Akhtar played over 100 combined One Day (OD) and T20 matches for Punjab, emerging as the team’s leading run-scorer and consistent performer in domestic competitions. In 2017, she was called for the national camp for the Indian women’s national cricket team, becoming the first woman cricketer from J&K to be selected. In 2019, she played for Trailblazers—a part of the Women’s T20 challenge competition, viewed as a response to the men’s Indian Premier League (IPL). The last tournament was played in 2022 and was replaced by the WPL in 2023.

Akhtar’s entry into the WPL marked a historic moment for women’s cricket in J&K. During the inaugural WPL auction held in Mumbai, the right-handed batter, who was 34 then, was selected by the Delhi Capitals at the base price of Rs 20 lakh, becoming the first and only player from the region to secure a contract in the league.

“I can’t express in words how I felt when I earned a spot in the WPL. I was ecstatic, on top of the world,” she says. Despite being a top-order batter for Punjab and later for Rajasthan and Uttarakhand, there was never enough money for her to invest in cricket paraphernalia. The slot in the WPL was truly a big deal. Although the base price was nowhere close to what the male players were paid in the IPL, Akhtar feels pay parity is important to encourage the participation of girls in the game. “The IPL started much earlier, so it’s understandable that they get paid in crores, and we are paid in lakhs, but it’s an important start. When I played in Mumbai during the WPL, the stadium was full. It’s only now that women’s cricket is seeing some investment in terms of marketing and promotion,” says Akhtar.

She has made over 5,000 runs in her career, which includes more than eight centuries and 15 half-centuries. She has played in the Premier League matches in Bangladesh. Her best has been an unbeaten 165 in the senior women’s OD match and 125 in a T20 game. She has played in the India A team. While her impressive batting average has helped teams to win matches, she is also a medium pacer who has taken wickets in crucial matches. Her recent achievements include scoring 450 runs in six matches in the senior women’s OD tournament in Vadodara. Her efforts helped the team reach the quarterfinals.

When asked which has been her favourite knock, Akhtar, who loves to play straight drive, says: “In 2022, I was playing for the Rajasthan Cricket Association. We managed to beat Mumbai after I scored an unbeaten 151. We were chasing the target of 255, and we were down 92/5. My knock helped the team win.”

As the captain of J&K’s senior women’s team, Akhtar is happy to represent Kashmir again. But the sea change that she was hoping for has not happened. “There are no separate training academies for girls in Kashmir even today. Most of the academies are run by men, keeping many talented girls away,” says Akhtar, who did not take up a government job as she wanted to focus on cricket. “People say that cricket is a man’s game. That’s incorrect. It’s very much a woman’s game as well. If a girl from a small village in Kashmir can play in Bangladesh, others can do it too,” she says.

For things to change, women need to have an equal say in policymaking, feels Akhtar. “You need a vet to treat animals and a doctor to treat human beings. You cannot make one do the job of the other. Similarly, academies should be handled by professional players and women should be included in policymaking. Only then, things will change,” she says. She aims to set up an academy in Kashmir exclusively for girls. “I have played for different states. Now that I am back in Kashmir, I want the Jammu and Kashmir Cricket Association to earn the top spot in the country,” she says.

Her homecoming has given her some time to reflect on past struggles. “There was a time when we didn’t have money to travel from my village to Srinagar for trials or to play matches. I am grateful to my family,” says Akhtar.

Her father, Gull Mohammad Wani, had to put in extra hours of labour whenever his daughter needed money to travel. “I would tell her to inform me in advance so that I could put in extra hours. Sometimes, the teachers would pitch in. Once, a teacher bought us a suitcase,” he says. Wani remembers how, as a child, Akhtar would refuse to part with her bat and ball. “She would say, instead of toys or candies, buy me a bat or a ball. She would cry for hours in case I forgot,” says Wani. Her brother, Nilofar Ahmad Wani, remembers Akhtar practising on the lawn and adds that he is proud of her, considering she has managed to make a mark in a “man’s game”. Her coach, Khalid Hameed, recalls how she also played volleyball and football, but he advised her to focus on cricket. “She had a good pace, and I thought she would be a great bowler, but she is also a terrific batter now,” he says. Ask her what message she has for other girls from Kashmir who want to play cricket professionally, she says: “Never stop dreaming, work hard and don’t get bogged down by difficulties. If I managed to achieve all this, others can too.”

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled No More A Gentleman's Game dated February 11, 2026 which explores the rise of women's cricket in India, and the stories of numerous women who defeated all odds to make a mark in what has always been a man's ballgame