Nepal’s political journey shows how authoritarian rule under the Panchayat system suppressed even basic freedoms, turning gatherings and free speech into acts of defiance while deep social inequities.

The memory of India’s covert pressure during Nepal’s 2015–16 constitutional crisis lingers, while today’s global asymmetry highlights how small states like Nepal lack the regulatory power that giants like the EU wield.

I began reporting from Nepal in the early 1980s, when democracy was a whispered hope and a dangerous word. Under the Panchayat system, in place since 1962, political parties were banned and the monarchy concentrated power the way a fist concentrates blood. Even arithmetic could be criminalised: if more than five people gathered, police could disperse the meeting and drag people away.

I watched it enforced in 1985 near New Road, a constable’s finger ticking off the sixth face at a tea stall as if the number itself were subversive. Those years taught me how fear turns neighbours into strangers, how a press ban deadens not only the public square but the imagination, and how unequal law breeds unequal life. Women could not inherit property; little girls were baited and brokered across borders for men who called it pleasure; boys were shipped to the dark economies of hard labour; poverty pressed people into choices that were not choices at all. Yet a struggle kept finding breath.

I interviewed leaders who were sometimes in jail, sometimes in hiding, sometimes in exile, and sometimes—when the border was porous to courage and friendship—sitting at my dining table in Forbesganj, fourteen kilometres from Nepal.

Girija Prasad Koirala spoke with a matter-of-fact cadence about strikes and repression; Ganesh Man Singh shuttled between hiding and house arrest; Mangala Devi Singh nursed the Nepali Congress women’s wing with more stamina than budget; Krishna Prasad Bhattarai brought the patience of a constitutionalist; P.L. Singh had the briskness of a street organiser; Pradeep Giri’s moral clarity could slice a slogan in half; Chakra Bastola carried a seasoned caution; Durga Subedi refused to confuse romance about revolution with its real costs.

In 1986 and 1987, I crossed into Nepal to meet them stealthily, leaving by different doors, or they arrived at my home in Forbesganj at odd hours and left before dawn. I filed those interviews in The Telegraph and, in 1988, the paper was banned in Nepal for a time; our words crossed a border and rattled a system that feared its citizens’ voices. What I learnt then has never left me: Nepal may be small and landlocked, but it is not weak. Its people carry moral stamina like a talisman. And the struggle for democracy is not an event; it is a craft practiced across generations, passed like a lamp from hand to hand.

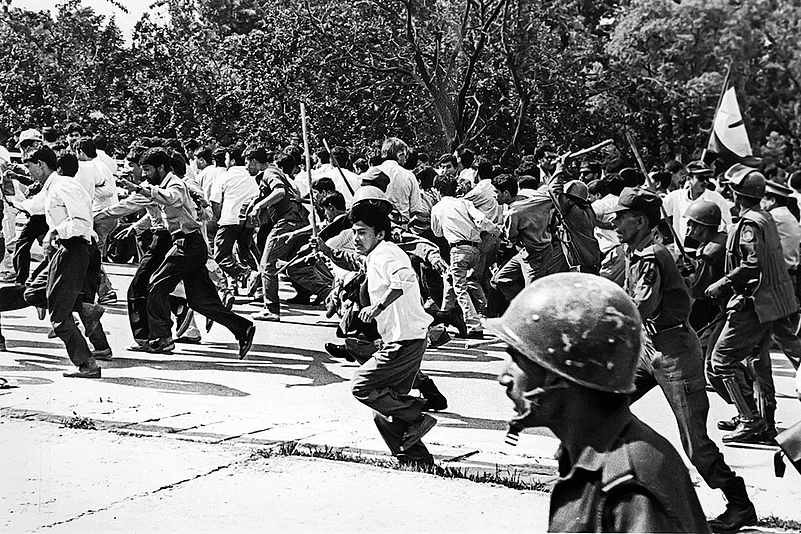

In February 1990, the People’s Movement—Jana Andolan—gathered force. Weeks of protests met weeks of crackdowns and, in April 1990, the king capitulated. That April felt like a hinge. An interim government formed, and in November 1990 a new constitution restored political parties and created a parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarch. The first free and fair elections were held in May 1991.

I can still feel the air of 1990–1991 in my lungs: the enthusiasm of May Day rallies, the July afternoons when a city learnt to walk differently, the press discovering it could argue with itself without whispering, the faces of organisers who had been in jail in 1985 now joking in the open about portfolios. But even in victory, the old habits clung. I remember Mangala Devi Singh, who had built the women’s wing through bans and surveillance, refusing to watch from the margins in 1991 as men with less history and more entitlement took cabinet seats. She ought to have been inside the room where portfolios were dealt; instead, she was thanked and sidelined because she was a woman even as she insisted on more representation for women and laws that favoured women from inheritance to health care. It was a familiar script across South Asia: the women, who carried movements on their backs are asked, at the moment of triumph, to carry tea.

The new order did not end instability. On February 13, 1996, a Maoist insurgency began that would run a decade. The first years saw a police-led counterinsurgency—under-equipped, poorly trained for a war it could not define—coupled with abuses like the 1995 operation that drove alienated, impoverished rural residents straight into Maoist arms. The insurgents spread across the countryside, set up parallel governments and collected taxes in zones where state presence grew thinner by the month.

On June 1, 2001, the royal palace massacre killed King Birendra and much of his family, shocking a nation and accelerating the slide. By late 2001, the Royal Nepali Army was deployed for the first time; the conflict escalated. Negotiations sputtered and failed; ceasefires were tested and broken. On February 1, 2005, King Gyanendra seized absolute power, dissolving the government and tightening control in a way that seemed to mock the decade-old promise of 1990. Girija Prasad Koirala resigned as Prime Minister in 2001 and negotiated beyond old enmities, inviting the Maoists to form the Seven Party Alliance, understanding that the way back from the brink would be a coalition for democracy—or no way at all.

In April 2006, Jana Andolan II—another People’s Movement—filled the streets. The alliance with the Maoists, precarious as it was, signalled a wager on politics over force. Facing immense public pressure, King Gyanendra reinstated Parliament on April 24.

From there, the logic of negotiation beat back the logic of escalation. In November 2006, the government and the Maoists signed the Comprehensive Peace Accord. It did not romanticise the insurgency or whitewash its wounds; it created a ceasefire, cantonment of Maoist fighters, a supervised path away from arms, and a promise to elect a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution.

In 2007, an interim government seated Maoist representatives—a moment that would have seemed impossible in 1998, when I stood at funerals and wondered what end-state could justify another grave. On May 28, 2008, the monarchy was abolished and Nepal became a federal democratic republic—not by firing squads but by ballots inside a hall.

If the insurgency ended without becoming an unending civil war, it is because negotiators—above all Girija Prasad Koirala—kept picking talk over blood. Koirala returned as PM, not as a man nursing grudges but as a broker-in-chief, building trust with Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda) while holding constitutionalists together, and then formalising the peace as prime minister. He had the gift, rare in our region, of speaking to palaces and to revolutionaries without becoming either.

The republic took another formal step on September 20, 2015, when Nepal promulgated a new constitution after seven bruising years of drafting. On paper, it was a bold settlement: Nepal declared itself an “independent, indivisible, sovereign, secular, inclusive, socialism-oriented federal democratic republican state,” spelling out secularism as both the protection of ancient practices and the freedom of religion and culture, while locking in federalism, republicanism and inclusion as constitutional facts rather than slogans.

Many upper caste Hindus residing along the Indian border read the design as pro-the tribal and middle and marginalised castes up in the hills, locking them out of fair weight; New Delhi quickly urged amendments. Then came the punishment everyone remembers by another name.

Within days of promulgation, India blocked the border, slowing crossings of trucks and goods to a crawl. Kathmandu called it an unofficial blockade. From late September 2015 into early 2016, the effect was the same: fuel and medicines ran short, schools shut, prices spiked, black markets flourished, and a landlocked people learned again how vulnerable daily life is to decisions taken outside the hills—just months after an earthquake. Aid convoys idled as winter closed in; hospitals cut rations; families queued for kerosene and insulin.

India publicly denied orchestrating the squeeze even as its diplomats pressed for constitutional changes; by December 2015 and January 2016, Kathmandu announced amendments to proportional representation and constituency delimitation that Delhi promptly welcomed. The memory—of overt advice, covert pressure and a choked border—has not faded; it colours how Nepalis still read Indian headlines and how quickly they recognise pressure when it drifts across the plains.

There is another asymmetry that has become impossible to ignore: small states regulate trillion-dollar social media platforms with far fewer levers than Brussels. The European Union can threaten fines tied to global turnover and win compliance through audits and binding orders. Kathmandu’s regulators can write notices and convene meetings, but they cannot make giants flinch the way Europe can. In 2015, the asymmetry shaped the border. In 2025, it shaped the blackout: enforcement, in a weak regulator’s hands, looks like a switch.

On September 4, 2025, the government ordered internet providers to block twenty-six social platforms that had not registered under new rules—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, X, Reddit, LinkedIn, Snapchat, among them. Officials said the goal was compliance and accountability: registration, a local grievance officer, cooperation with lawful requests.

In principle, Nepal was not asking for anything exotic; the European Union’s Digital Services Act requires in-region legal representatives and transparency, and India’s IT Rules require a Resident Grievance Officer, a Chief Compliance Officer and a Nodal Officer. But method matters as much as mandate. Brussels disciplines platforms with investigations and fines measured against global turnover; New Delhi mixes pressure, litigation and public theatre to coax concessions without plunging millions into darkness.

Kathmandu reached first for the blackout—and it did so while the youth were already seething about inequality and impunity. For organisers who run everything from first aid to blood-donor lists on Discord and Instagram, the ban felt like a hand over the mouth.

September 8 will be remembered for the streets that overflowed. The first day’s marches were disciplined and enormous, like April 1990 and April 2006. Students and recent graduates—many underemployed or with migration on hold—carried placards not about kings or temples but about impunity: “Shut down corruption, not social media,” they chanted at Maitighar Mandala and New Baneshwor. The state responded with tear gas, water cannons and rubber bullets; by nightfall, at least nineteen people were dead.

On September 9, mobs exploited chaos—many not students. Eyewitnesses I trust described royalist and Hindutva cadres in the crowds, rudraksha rosaries at their necks, slogans alien to the students’ demands, homes burned and shops looted. Parliament burned, the Supreme Court compound was attacked, the residences of senior politicians were torched, and Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli resigned.

In those same hours, some Indian newspaper headlines obliged the misreading; a Hindi front page declared that “Gen Z wants a Hindu rashtra,” and the phrase travelled farther than any correction. A daily wage labourer’s pain and a student’s frustration became raw material for the King to stage a comeback on the backs of nostalgia and Hindutva.

The royalist courtship of Hindutva power centres has not been subtle. In April 2021, in the heart of the pandemic’s second wave, the former king and queen returned from India’s Kumbh mela at Haridwar and tested positive for COVID-19—a pilgrimage-turned-headline that underlined where the ex-royal household sought both legitimacy and blessing.

Four years later, in January and February 2025, Gyanendra travelled to Gorakhpur and Lucknow, offered khichdi at the Gorakhnath math and met Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, with royalist organisers in Kathmandu soon plastering Yogi–Gyanendra posters at rallies. And this was not a new improvisation: a decade and a half earlier, Nepali royalists and India’s Hindu Right had already been “brainstorming” together—at the RSS headquarters in Nagpur, at VHP and BJP offices in Delhi, at the Gorakhnath temple in Gorakhpur, and with Gyanendra at Narayanhiti Palace. The message across these years has been consistent: keep a live line to the RSS–BJP ecosystem and seek a sanction for restoration of a Hindu kingdom led by the King from across the border. Royalists and Hindutva lumpen tried to stage a comeback for the king; Delhi’s loudest voices in the media amplified the script.

What steadied the week, however, was the duet that steadied earlier decades: young organisers with a gift for logistics and elders with a memory for exits found each other in the smoke. In Discord servers, that sometimes counted more than ten thousand, moderators who had been tying tourniquets on September 8 were tallying names on September 10 for a caretaker who could hold the ring without inflaming faction or palace.

The conversation moved from rage to process. President Ramchandra Paudel refused to scrap the Constitution or play with the monarchy. The army, which could have auditioned for politics, counselled restraint instead. The students and the old democrats held to the constitution.

On September 12, after consultations that included youth representatives and security chiefs, the president appointed Sushila Karki—former Chief Justice, incorruptible and famously unwilling to bend even to her own party—as interim prime minister.

Parliament was dissolved for elections set for March 5, 2026. On September 13, curfews lifted in and around Kathmandu; Karki visited hospitals and promised to serve diligently. The toll had climbed past fifty; over 1,300 were injured; families demanded martyr recognition and compensation and, in some cases, refused to accept bodies until the state recognised their loss.

Calm is not closure. But in a week designed for a coup of memory, Nepal staged a defence of law. If there is a constant in this long story, it is the choice, again and again, to tame violence with skilled negotiation.

In 1990, talks opened the door the streets had forced. In 2006, the Seven Party Alliance stitched a hard partnership with the Maoists to face down a king, and in November that year negotiators turned ceasefires into a Comprehensive Peace Accord with cantonment and an electoral path. In 2007, an interim government seated the former insurgents. In 2008, the monarchy ended with votes, not volleys.

And in 2025, when a week of rage could have become a season of vengeance, students and elders converged around a neutral referee and moved the country into a constitutional caretaker phase. Each time the threshold beckoned—coup, insurgency, blackout—the better craft prevailed: talk before force, process before spectacle, law before charisma. I saw those practices in rooms where people spoke softly and risked much, and I saw them on streets where people spoke loudly and risked more.

None of this excuses impunity. The republic’s most corrosive wound is not only illegality but the belief that lineage absolves and power insulates. I think of Mangala Devi Singh in 1991, thanked and sidelined. I think of property codes that denied women equal inheritance for decades and how long it took to write equality into law. I think of the girls I met in 1987 and 1989 on the Indian side of the border, trafficked from villages that could not feed them. I think of the sons and daughters of those who once spoke in the accents of sacrifice now broadcasting privilege in winter while ambulances run out of fuel and schoolchildren share textbooks because a procurement went somewhere to die.

The students in September did not speak like ideologues; they spoke like auditors. They asked that rules bind the rulers first.

What comes next must honour that ask. Investigations into the September deaths should be independent and measured in weeks, not years. Compensation should reach families without humiliation. Platform governance must be rebuilt as a ladder—notice, deadline, fine, narrowly tailored order—rather than a national switch.

The Election Commission must turn March 5, 2026 into a living operation with procurement, training, security perimeters and dispute-resolution panels that function in real time. Parties must resist turning the caretaker period into a bazaar of spoilers. And India, if it wants a stable neighbourhood, should lend empathy rather than templates—press for compliance mechanisms that do not silence users, call out monarchist mis-framings in its own media, and remember that the job of a big country is to steady a small one, not to lean on it.

When I think back to 1984, to a union organiser in a blue shawl who had just been released from jail and began our interview by making tea on a coal stove, I remember what she said into the steam: nothing frightens a tyrant more than people who won’t stop making tea. She teased the policemen who trailed her and sent them home with a thermos when it snowed, because cruelty should never have warm hands.

This September I saw her stubbornness in younger faces: organisers who posted de-escalation rules when looters arrived; medics who cycled bandages from backpacks; moderators who turned rage into process by counting votes for caretaker names in rooms that might once have been used to plan a concert. I saw a president hold the line; an army step back from temptation; elders who could have pivoted to nostalgia broker a lawful exit when nostalgia was the easiest sell on the street. I saw, in short, a small country remain a republic—even as a neighbour’s loudest voices urged a crown and as platforms built on distant shores proved harder to discipline than any palace had ever been.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

I also remember the summer of 1988, when my interviews in The Telegraph were banned in Nepal and a complicated pride rippled through our newsroom. The ban did not last. The people did. In April 1990, they made a constitution; in April 2006, they made a path back to one; on May 28, 2008, they made a republic; on September 20, 2015 they made another constitution; in the lean months that followed they learnt again what a blockade can do; and in September 2025 they made a choice, again, to keep faith with law over spectacle—resisting, despite pressure from Hindutva lumpen and a would-be king, and despite the structural weakness of a small regulator facing global platforms. The same lamp passes from hand to hand. It takes more than wind to put it out.

(Views expressed are personal)

(The article appeared in the Outlook Magazine's October 1, 2025, issue Nepal GenZ Sets Boundaries as 'Throwback To The 80s')