Sandeep Naik, 48, runs a general store near the Sateri temple along the Boma-Adcolna road, in Ponda, a hinterland taluka. Less frequented by mainstream tourists and tucked away from the Lusophone-inspired landscape along the coastline, Ponda often hides in plain sight and is known as the ‘Hindu’ part of Goa. Naik sustains his livelihood through local visitors to the temple. However, his shop, along with others, faces demolition due to an ongoing National Highway expansion exercise.

As Goa went to polls on May 7, the proposed displacement was a major electoral issue in Boma village, with 3,000 voters, which is one of the four assembly constituencies in Ponda and the only one that falls under the North Goa Lok Sabha constituency. “Both our MP and MLA is from the BJP,” Naik informs.

Naik and other vendors have been allocated shops at a new market complex. “Temple visitors were our main customers,” he states. Portions of three temples, including the one dedicated to the goddess Sateri, are slated for demolition, upsetting locals like Kishore Naik, who also faces displacement. Villagers have demanded a bypass and challenge plot allotment to non-Goans in the area. “These temples are integral to their identity, says Naik.

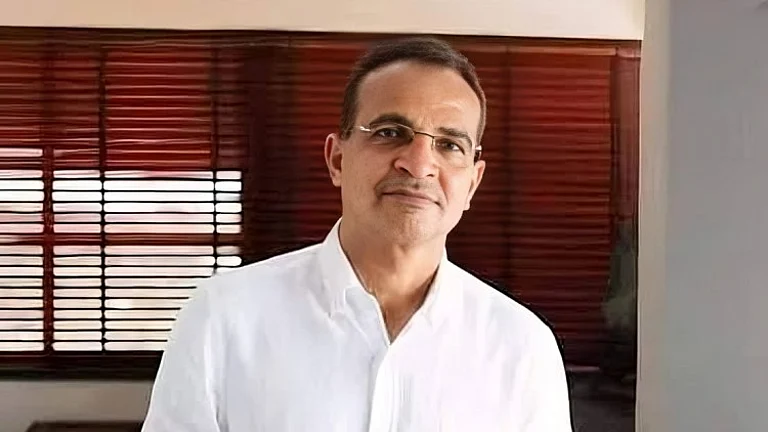

Local residents claim to support the Congress this time. The party has fielded 77-year-old former union minister Ramakant Khalap, who has promised to resolve the national highway issue if he is elected. Khalap faces-off with the BJP’s heavyweight five-time incumbent MP and Union Minister, 71-year-old Shripad Naik. Defying the humid coastal heat, the two septuagenarians and their teams have been actively campaigning across Goa. “I am confident of victory,” says Naik.

In South Goa, the BJP’s candidate is Pallavi Dempo, an ostensible political “outsider” from the influential Dempo and Timblo families, who, put together—along with a few other clans—account for the traditional mining lobby in Goa.

An industrialist and the richest candidate to contest in the third phase of Lok Sabha, Pallavi said at a campaign rally in Ponda: “I will continue the development work being done by the BJP in Goa and take Modi ji’s vision forward.” Campaigning for the political “outsider” are four heavyweight ministers and sitting MLAs elected from Ponda taluka—Ravi Naik (Ponda), Sudin Dhavalikar (Madkai), Govind Gaude (Priol) and Subhash Shirodkar (Shiroda).

With the Congress weakened by defections (eight of its eleven MLAs are currently in BJP), the Goa government which has been dubbed ‘Congress-yukt BJP’ faces anti-incumbency in some parts due to unmet promises of employment, inflation control, infrastructural development and environmentally safe restoration of the iron ore industry. Concerns persist over job losses and large-scale land purchases by outsiders.

Insider vs Outsider

Perhaps as a reaction to the majoritarian trends currently dominating politics in many parts of India, the average Goan seems to have become acutely aware of the ‘Goan identity’ and many fear that the “real Goenkar (Goan)”, be it Hindu, Christian or Muslim, is becoming obsolete due to a feverishly growing migrant population across Goa.

“Goa is a very small state with a unique demography. Today, the migrant influx has increased so much that native Goans are losing everything. We are losing our land rights, our jobs, housing, our unique identity, culture and even our peace because of this migrant influx,” says Manoj Parab. The RGP drafted the Person of Goa Origin Bill 2019 which defines a “A person of Goan Origin” as one who who is or whose either parent or grandparent was born or permanently lived in Goa prior to 20 December 1961. “The BJP blocked it,” he adds, stating that they will push for the bill if they win.

“We (RGP) are fighting for the rights and identity of the Goans. But there will be no Goans left to defend if there is no Goa left for us”

“Be it North or South Goa, Goans are running out of land. All of our land is being bought by outsiders. We (RGP) are fighting for the rights and identity of the Goans. But there will be no Goans left to defend if there is no Goa left for us,” says Parab.

He adds that the rising migrant population is also responsible for another new strand in Goa—the politics of religious majoritarianism—that has affected the state’s delicate social fabric.

Ruled by the colonial Portuguese for 451 years, Goa has a high percentage of Christian population. Located mostly in the Old Conquests talukas like Salcete in the South Goa district, Bardez in the North and Tiswadi (in North Goa district), Christians form the second largest religious group in Goa after Hindus, followed by a minority Muslim population.

In August 2022, the idol of local deity Vijaydurga appeared mysteriously at Our Lady of Health Church in Sancoale, near the home of the Congress candidate in this Lok Sabha election, Captain Viriato Fernandes. Similar incidents have occurred before, too. Statues of Chhattrapati Shivaji Maharaj have also begun peppering the state’s populated (and remote) pockets, triggering alarm in some quarters. In February 2024, a statue was forcibly installed in Sao Jose de Areal village, triggering disputes and FIRs against objectors.

“We were not against Shivaji or the construction of the statue, but only against illegal construction. We objected as these are tribal areas and any construction must be done with the permission of local authorities,” Sao Jose de Areal Panchayat member Joycee Dias states.

With the BJP government promoting temple construction nationwide, Goa’s temples, once discreet, now prominently display saffron flags depicting deities like Lord Rama or Hanuman. Nikit Naik, a Ponda tableau artist and member of Mahalaxmi Nagri Samiti, notes a surge in religious festivities, providing more job opportunities. Previously limited to Narkasura and Shigmo festivals, now events like Ganesh Chaturthi and Ram Navami also offer employment for artists like him.

Not all Ponda residents appreciate the growing religiosity, though. Local political activist Surel Tilve hails from a family of mahajans (priests in charge of maintaining temples) in Nageshi. He feels there is no problem with promoting festivals or sprucing up temples but argues that repeated allusions to “reclaiming Hindu temple lands” are a political rather than religious move. Since becoming chief minister, Pramod Sawant has repeatedly mentioned the need to remove “symbols of Portuguese rule” from the state. In 2022, the Goa government allocated Rs 20 crore for the reconstruction of temples and Goan heritage sites that were damaged by the Portuguese.

“The government first announced a survey to determine how many temples were demolished by the Portuguese and said it will rebuild those temples on the old sites. It later changed tack and said it will construct temples wherever possible. Eventually, they said they will build one memorial to commemorate the temples. In the end, it was all just pre-poll jumla,” Tilve states.

Former Nuvem MLA and political activist, Adv. Radharao Gracias feels that identity politics is just a cover for vested political interests. “Look at the candidates. Pallavi comes from Dempo and Timblo families that had intimate connections with Portuguese before independence,” he argues. “The BJP says it will remove Portuguese symbols from Goa. These families are also remnants of Portuguese rule,” Gracias half jokes.

The Dempo Group, established in 1941 by Vasantrao S. Dempo, whose grandfather served in the Portuguese Parliament, has ties to the Timblo family through Fomento Group, founded by Modu Timblo. Both families, prominent BJP donors via electoral bonds, also support the Ram Mandir. Pallavi Dempo is married to Vasantrao’s grandson, Shrinivas, while she is the niece of Audhut Timblo of the Fomento Group of Companies. BJP MLA Divya Rane, wife of Goa minister Vishwajit Rane, also belongs to Timblo family.

At the time of the temple consecration in Ayodhya, Shrinivas Dempo had tweeted: “It’s a matter of great pride to see the massive redevelopment of Ayodhya before the reopening of the Ram Mandir at the birthplace of Shri Ram.” He was also present in Ayodhya at the time for the pranapratistha ceremony. But in Goa, focus seems to have shifted from Ram to Shivaji, often dubbed as the“Hindu Hriday Samrat.”

‘Ajeeb’ Allegiances

Political commentators observe a resurgence of “pro-Maratha” sentiment in Goa’s ‘Maharashtrawadi’ politics, evident in the proliferation of Shivaji statues and the rise of “Shiv Premis” under the BJP. The Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party (MGP), for whom Marathi pride has been a calling card and had initially advocated for Goa’s merger with Maharashtra, won the first assembly election in 1963, but faced defeat in the subsequent 1967 Opinion Poll—India’s first and only referendum—against the anti-merger United Goans Party.

“Goa is the birthplace of Konkani. The language agitation to save Konkani went on for over 500 days. It was a time when leftist ideology and people’s movements were strong across the state,” Jnanpith awardee Konkani academic Damodar Mauzo states. By the late 80s, many leaders from MGP and UGP had joined the Congress and CM Pratapsingh Rane (ex-UGP) who was pro-Marathi, had no option but to go for an amicable solution at the time. Konkani was hence declared the official language, while “Marathi was also allowed to be used for official purposes,” he said.

The language agitation changed the politics of Goa, which attained statehood in May 1987, resulting in assembly constituencies in the state increasing from 28 to 40. “The four talukas of Old Conquest which were at the forefront of pro-Konkani agitations, now became a dominant force with 22 assembly seats, while the remaining seven talukas in New Conquest, pro-Marathi areas, got just 18 seats,” says journalist Sandesh Prabhudesai, author of Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics.

In 1989, Congress secured power in Goa, notably winning 15 out of 20 seats in Old Conquests like Salcete, holding 41 per cent of the vote share. This marked MGP’s decline, with many of its leaders joining the BJP. Congress’ nomination of Khalap, a former MGP figure, suggests acknowledgment of the “Maratha lobby” influence.

Commentators like Prabhudesai nonetheless add that frequent defections make it hard for Goans to form allegiances to parties or ideologies. Reflecting on the persistent problem of political defections, Bardez-based artist Subodh Kerkar jokes, “Goa was once known as the hub of trading Arab horses. It remains a hub of horse trading to this day.”

“Since the constituencies are much smaller, most Goans vote on the basis of the candidate’s personal connect with people, their wealth, social and educational background. They want to see who can work the best for their specific area,” Prabhudesai states. He insists that caste and religion have not been deciding electoral factors for Goan voters in the past.

Meanwhile, voters across South and North Goa claim their woes remain unheard. In the mining blocks of Bicholim, for instance, residents from villages like Lamgao, part of a new mining lease, have started protesting against the resumption of mining. “A mine located just 100 metres from our village became operational in April. Such close proximity (to mining activity) causes increased dust and sound pollution in foothill villages like ours. We get muddy water in taps and face long-term health impacts like breathing problems,” says Rajitha Hoble, mother of two. “How can a government allow such activities?”

Traditional coastal communities have also been struggling in the face of a swiftly concretising Goa. “Professions like fishing, cashew cultivation, etc., have been diminishing in wake of the growth in tourism sector, which is dominated by wealthier migrants from Mumbai, Delhi, etc. The government promotes tourism, which, in turn, leads to a rise in land prices,” says fisherman and union leader Jose Fernandez of the Kharvi Bhavacho Ekvot in Benaulim.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

A member of the disappearing traditional ramponkar community of fishermen, Fernandez has been vocal against the cultural and environmental perils of mechanised fishing. “The sea is the source of our livelihood and identity. But we have scared the fish away,” he rues. “No parties seem to care about that.”

Rakhi Bose in Panjim, Bicholim and Salcete

(This appeared in the print as 'Sun, Sand and Saffron')