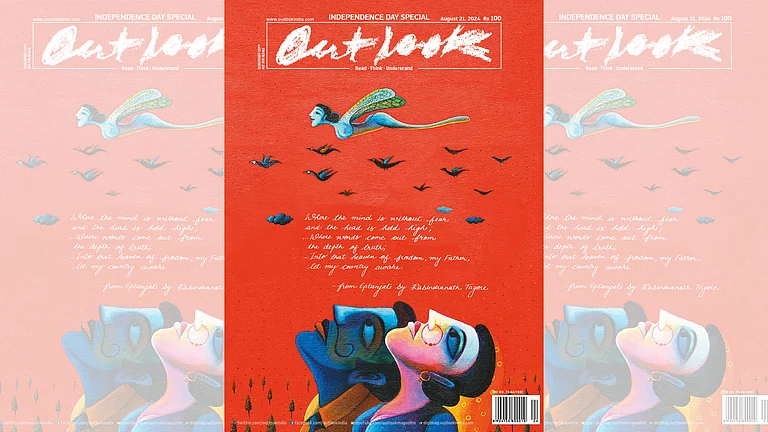

Reading in Kashmir is not leisure but survival—an act that preserves memory against forgetting and resists enforced silence.

Books provide shelter and nourishment, creating inner spaces of freedom and sustaining imagination when horizons narrow.

Passed down as fragile inheritances, books bind generations together, forming a quiet but unyielding grammar of survival.

In many Kashmiri homes, tucked into trunks or stacked on shelves darkened with dust, there lies a book that seems more alive than inanimate. Its pages are browned at the edges; the spine is frayed from repeated touch. Inside, there are small traces of those who once turned its leaves: a name written in careful ink on the first page, a smudge where fingers lingered too long, a pressed flower flattened into silence, margin notes scribbled in faded Urdu or Kashmiri.

These marks, accidental and deliberate, are not mere decoration. They are evidence of lives lived, of thought carried forward, of memory refusing to die. To open such a book is to enter a conversation that has survived across time and disruption.

In Kashmir, the act of reading is never only about text. It carries with it the weight of inheritance. Each underlined verse and folded corner is a quiet signal that someone before you sought meaning in the same lines, perhaps in similarly uncertain times. Reading becomes an intimate gesture of continuity: you breathe through the pages as those before you once did.

This intimacy is not an ornament, nor a leisurely pursuit. In a place where silence is heavy and forgetting comes easily, reading is survival. It shelters memory from erasure, nourishes imagination when horizons shrink, and affirms dignity in the face of interruption. A book, with all its stains and scribbles, becomes more than an object; it becomes a small act of endurance. To read in Kashmir is not to escape reality, but to insist, quietly and stubbornly, on keeping alive what might otherwise vanish. Reading, here, is breath itself.

Memory Against Forgetting

If survival in Kashmir requires breath, it also requires memory. To forget is easy; forgetting, in fact, is often convenient. But memory —fragile, contested, sometimes painful — is what sustains a people through interruption. Reading is the most reliable way to hold on to that memory. Oral stories fade, witnesses are silenced, but the written page endures, carrying across generations what would otherwise be lost.

Every book in Kashmir is thus more than paper and ink. It is a vessel of continuity, a record of thought that survives the fragility of speech. When a poem by Iqbal is copied into a school notebook that resurfaces decades later, it is not nostalgia alone. It is proof that the past resists erasure. Reading becomes political precisely because it makes erasure difficult.

Think of a library not as a collection of books but as a granary: each volume is a grain stored against famine. In times when official stories change with the season, when words are replaced or made to vanish, these books remain as stubborn fragments of truth. To read them is to feed oneself with memory, to prevent hunger of the spirit.

Every act of reading here hides an argument. To pick up an old history, leaf through a banned novel, or return to a collection of Kashmiri verse is to declare, silently, that memory matters more than forgetting. Reading refuses the temptation to live only in the present moment, stripped of roots. It insists on continuity, however fragile.

That is why reading in Kashmir is never passive. It is an act of preservation, a way of refusing the slow violence of amnesia. Each page turned is a thread tightened against rupture. Each word read is a breath drawn against silence. To read is to remember, and to remember is to survive.

If memory preserves the past, shelter protects the present. In Kashmir, outer spaces are rarely neutral. Streets, classrooms, and even conversations carry a weight of watchfulness, interruption, and uncertainty. To read is to step into a space that stays untouched by that weight. It is to close a door, even if only in the mind, and to open a window that no one else can see.

The intimacy of reading is its quiet power. A student hunched over a novel under candlelight, a young woman copying verses into her diary, or an old man revisiting scriptures in the corner of a mosque all inhabit a kind of interior freedom that is difficult to intrude upon. Unlike public speech, which can be monitored or silenced, reading is a private dialogue between the reader and the text. Within its pages, one is unobserved, unguarded, and free.

This freedom is subtle but profoundly political. It does not announce itself with slogans. Instead, it creates an inward room that cannot be occupied. Even when outer worlds collapse, a reader carries within them a house that is portable and unbreachable. Books become keys, unlocking this hidden architecture of freedom.

Words on a page have a sheltering quality. They absorb fear, offer companionship, and steady the mind against uncertainty. Reading allows one to enter another rhythm of time, slower and less anxious than the hurried urgency of the world outside. And in that rhythm, the reader rediscovers dignity.

This is why, in Kashmir, reading is not escapism. It is not a flight from reality. Instead, it is a way of creating a livable space within reality’s confines. To open a book is to open a room within oneself, a shelter that does not crumble under watchful eyes. In that shelter, one can breathe freely, even if only for a while. And to breathe freely, here, is already survival.

Against the Barren Horizon

Survival is never only about the body. To live with meaning requires more than bread and shelter. It needs nourishment for the spirit, a sustenance that keeps imagination alive when horizons grow narrow. In Kashmir, reading offers that nourishment. It feeds the mind with possibilities and prevents the slow starvation of thought.

Books provide a kind of sustenance that is not visible but deeply felt. A single poem can steady a person through despair, and a history book can remind a reader that the present moment, however heavy, is not eternal.

A novel can open windows to lives elsewhere, making it possible to imagine other ways of being. Without such nourishment, life is reduced to bare survival. With it, one can endure with dignity.

The image of grain is useful here. Just as a seed contains the potential of an entire harvest, a book holds within it the possibility of whole worlds. Reading is the act of planting that seed within the self, allowing imagination to grow in soil that might otherwise harden. In this sense, every page is cultivation. The more one reads, the more one resists the barrenness of silence.

This cultivation is not simply private. A community that reads together cultivates resilience. Students sharing books, families passing down stories, or poets reciting verses, all contribute to a collective nourishment that makes despair less total. Reading allows people to live not only in the immediate present but also in the long sweep of history and the vast terrain of imagination.

Those who seek to narrow horizons know the quiet power of reading, which is why books are often treated with suspicion or neglected in public life. To read, then, is to widen the horizon again. It is to insist that even in times of constraint, the mind can stretch toward other skies.

Reading nourishes imagination in ways that make survival more than endurance. It turns life into something that can still be dreamed, hoped for, and shaped.

Unsteady Inheritances

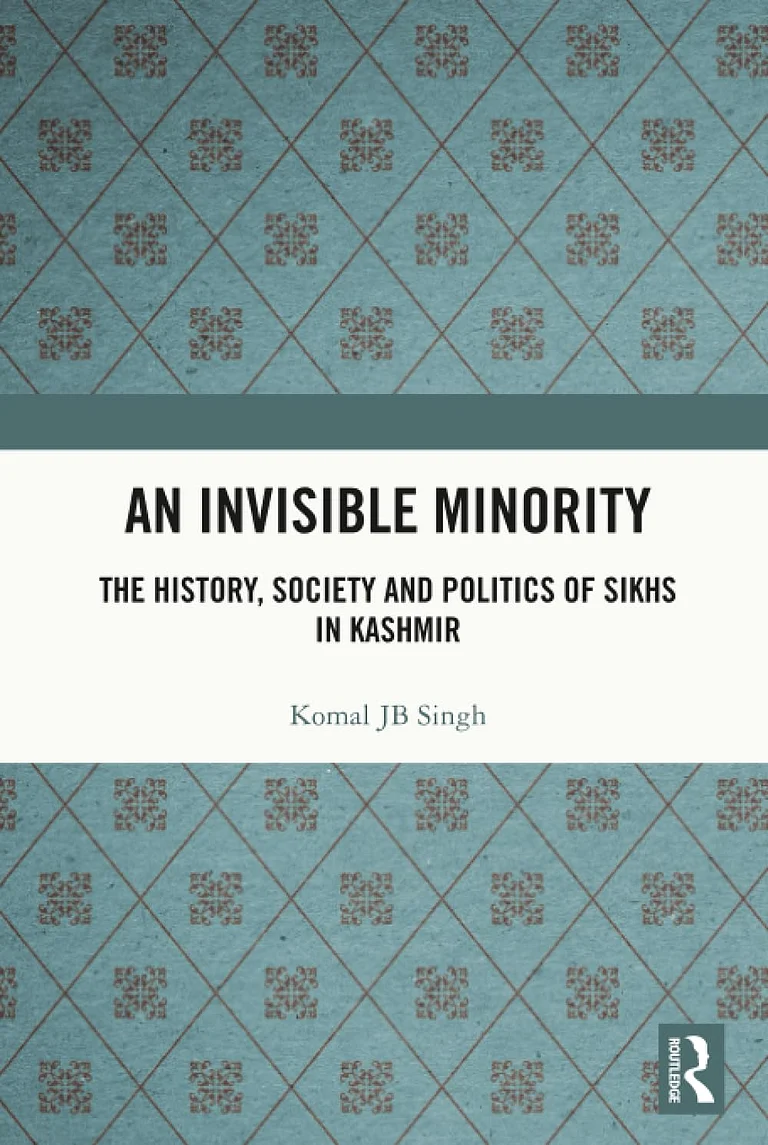

If shelter offers protection in the present, inheritance ties us to the past and projects us into the future. In Kashmir, books are often the most fragile yet enduring form of inheritance. A volume passed from one generation to the next does not simply carry words; it carries traces of those who held it before. A folded corner, an underlined verse, or a note in the margin is a quiet reminder that the act of reading was once shared, and can be shared again.

To read what another has read is to enter into an unspoken conversation across time. A grandchild who finds a grandfather’s annotations in a history text is not only encountering the past but is continuing it. The book becomes a thread binding different lives into a single fabric. In places where rupture is frequent, such threads are invaluable. They allow continuity to persist even when other bonds are broken.

Books also pass down more than knowledge. They transmit values, emotions, and ways of seeing the world. A poem recited in childhood may resurface years later with new resonance, reminding the reader that meaning is not fixed but unfolds across generations. The act of reading renews inheritance, keeping it alive rather than letting it calcify into a mere relic.

This continuity is vital in Kashmir, where interruptions of life, education, and speech are frequent. Without books, each generation would be forced to begin again, with little sense of what came before. Reading prevents that isolation. It allows the present to converse with the past and ensures that the future will have something to inherit.

To open a book, then, is to knot together the fraying threads of time. Each act of reading strengthens the weave against rupture. What survives is not only the text but the assurance that one’s story is part of a larger chain. This, too, is survival: to remain linked when the world would prefer disconnection.

The Grammar of Survival

In Kashmir, where silence is often enforced and speech monitored, reading becomes more than a private act. It is a grammar of survival. To read is to practice a form of endurance: of memory against forgetting, of thought against censorship, of identity against erasure. The fragile pages of books — scribbled upon, preserved, hidden, or shared — hold together what conflict constantly threatens to dissolve.

This grammar is not written in abstractions but in lived gestures: a family preserving a grandfather’s Quran with his annotations; students sharing photocopied texts when schools are shut; a poet’s verses carried quietly across checkpoints. These acts of reading and preserving do not make headlines, yet they shape the unseen architecture of Kashmiri resilience. They are the infrastructures of cultural survival.

Survival, here, is not only biological but intellectual and emotional. It is the continuation of a people’s capacity to imagine themselves otherwise than as subjects of control. Reading keeps alive questions and possibilities that the present seeks to foreclose. It binds fragments of the past into forms of meaning that can sustain hope in the future.

Thus, the book in Kashmir is never just a book. It is a vessel of memory, a shelter for language, and a thread of continuity. To open its pages is to resist silence, to carry forward what is worth remembering, and to write oneself into existence even without a pen. In the act of reading lies a quiet but unyielding declaration: we survive, and in surviving, we remember.

Huzaiful Reyaz is an independent researcher and journalist based in New Delhi. He writes on politics, religion, and identity in South Asia, with a focus on Kashmir.