A rusted pocket watch at the Partition Museum symbolizes how ordinary objects preserve extraordinary memories of 1947’s violence.

Historians warn that political rewriting of textbooks risks erasing lived experiences and authentic truths of Partition.

Museums and curators use oral histories, keepsakes, and postcards to safeguard personal narratives against dominant state-driven histories.

Lest we forget,

It must never happen again.

A rustic pocket watch, which has long lost its shine and its chain, can no longer point to the time. An item that seems ordinary, or perhaps even less than ordinary.

This watch now resides in the Partition Museum in Amritsar―it once helped a family identify their father’s body after he was shot dead during the Partition. “He was the only person in the village who owned a pocket watch,” said the grandchildren while donating it to the museum.

While the watch can no longer tell the time, it reminds us of a time we must never forget.

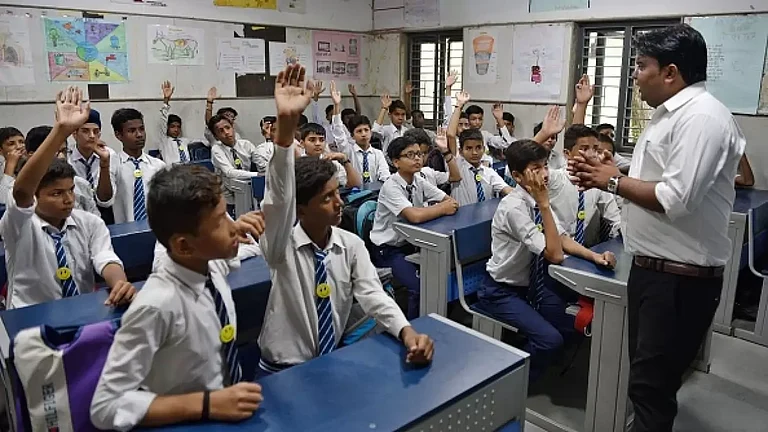

The recent changes in the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) history syllabus have reignited the debate of history being rewritten on the whims and fancies of those in power. Specific changes have been made in textbooks regarding the role of the Congress and the Muslim League in the Independence struggle, colonialism and the Partition of India.

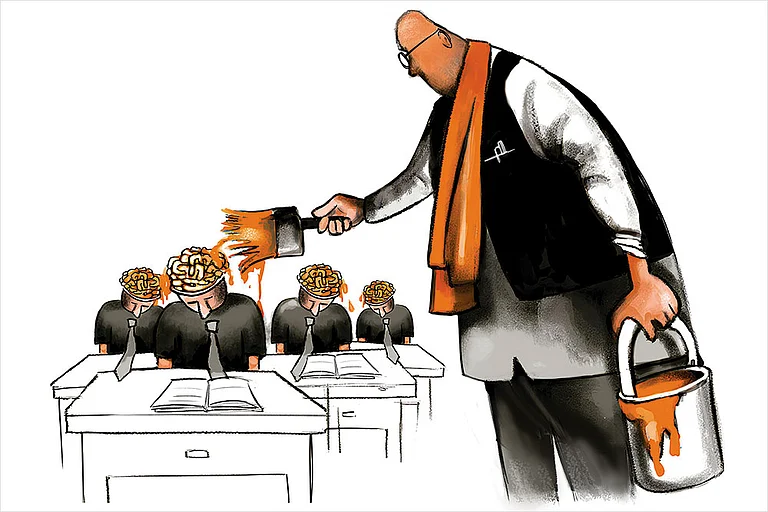

Education has long been a ‘political playground’ for propaganda. However, while history books teach the youth the ‘facts and figures’ of history, the lived experiences and memories of Partition remain as an unwavering narrative of the country’s darkest hour.

Sanjay Subodh, a history professor at the University of Hyderabad, believes that politics and history determine each other. He says, “Fascist regimes, in their own way, would always like to control the writing of history and control the narrative.” He claims that the manipulation of history being manipulated is not unique to the current times. “When we look into the colonial masters, they also tried to control the writing of history or how the narrative would go.”

While he holds that such practices by regimes are ethically wrong, he says it is not something “unnatural”. “Rewriting has always disturbed the way history is presented. Then the problem arises that the ‘new version’, which goes on to be taught, is not scientific and lacks evidence. With pressure from the regime, it becomes more popular and becomes the ideology that the state and the nation subscribe to,” he says.

Subodh stresses that rewritten history is riddled with a lack of scientific proof, methodology, process and corroboration, if dismantled from a historical lens.

“As a historian, one is not allowed to accept facts on their face value, but the politicians would always demand the acceptance of facts on their face value, which may not be possible to go through the rigour of scientific temperament but it is more usable for their own political ideology and that kind of writing history―whether it is written in the name of the nation, whether it is the name of a caste, whether it is the name of a religion or whether it is the name of a society―becomes very dangerous and detrimental not only to the present, but also to the future generation,” explains Subodh.

“When politics determines the course of history writing, it leads to the political indoctrination of people’s minds and this political indoctrination of mind that determines the politics, is never out of the reach of the people who want to control it, and through history, they control the minds of the people,” he adds.

With the generation that witnessed Partition as adults and is now in the evening of their lives, the horrors that followed Independence, once sworn never to be forgotten, stand at risk of fading away with every rewrite of history and every personal account erased from the texts.

A crisis for authentic material of the Partition plagues history. To resolve this gap, museums have taken unconventional, indirect yet raw sources to recount the Partition: memory.

Partition-affected families have come forward to donate their keepsakes from that time, and private collectors are donating postcards from colonial India to tell the history of a Partition that affected lives.

Lady Kishwar Desai, who hails from a family affected by the Partition herself and spearheaded the effort to establish the Partition Museum, found it “shocking” that India did not have a museum honouring the remnants of the nation’s birth.

She says, “So much of the actual horrors that happened during Partition have been left out of our history books. What is taught are the facts and figures, an overview of when the Partition was, how many were displaced and how many died.”

Seventy-eight years later, the Partition Museum in Amritsar and Delhi remain as the only memorials of the Partition.

While working to establish the museum, Desai found herself to be one of the very few who requested to see personal accounts of people at the Nehru Memorial archives. “This is literally an untouched part of our history,” claims Desai. “This is why our museum is dedicated to those voices that have been silenced in history.”

In Bengaluru, the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) curated a collection of postcards from colonial and post-colonial India, titled ‘Hello & Goodbye: Postcards from the Early 20th Century’. Curators Khushi Bansal and Meghana Kuppa spent days sifting through 13,000 postcards to piece together narratives of Indian lives under colonialism.

Bansal believes much of history has been reduced to statistics and numbers that students are forced to memorise. Between those pages, the actual lives of people are often left out. “That’s why a collection of communication from that time, like these postcards, is so important for the public,” she says. “It humanises the numbers and shows the life behind the figures.”

Kuppa adds, “History will constantly be reinterpreted. There will be various histories. Some will look at history holistically, others might omit a lot of information; that’s why these microhistories that we have documented need to be constantly revisited."

Thus, as museums turn away from the larger, ever-changing narrative of Partition and colonialism, personal accounts and glimpses into the lives of people at the time have become tools to weave the narrative of trauma and remembrance.

In the aftermath of the Partition in 1947, trucks carried stacks of unidentified Hindu bodies to the riverbanks for cremation. Amid the sorrowful last rites, a Jan Sangh member, Kishori Lal, recognised one of the bodies—Pt. Devi Dass from Nusserhra, in what is now Pakistan.

Not knowing the family, Lal turned to the Hindu Daily Newspaper, placing an advertisement about the pocket watch found with the body, hoping someone would recognise it. The notice reached Dass’s son, Madan Mohan, who immediately connected the pocket watch to his father. With his father already cremated, he went to collect the watch from Lal, his family’s solitary keepsake, which had been donated to the Partition Museum to keep the tragic memory alive in the narrative of the past.

The pocket watch is among hundreds of objects that survivors and their families have handed over to the Partition Museum: letters, photographs, locks, suitcases, and scraps of fabric. Each of them, in their ordinariness, holds the extraordinary weight of memory.

One such letter was sent to an officer in the undivided Indian Army, urging him to enlist in the ranks of Pakistan’s newly formed army. A simple lock once fastened a suitcase packed by a mother for her child, leaving for India. Inside it were a few precious goods—a dari, a khes (sheet), some cloth, a thaal (large plate)—the bare minimum to begin a new life after being forced to pack an entire world into a single suitcase and abandon home forever.

Desai went the extra mile, documenting oral histories for the Partition Museum. She found that many survivors of Partition wanted to retell their stories, believing it is time for the Indian public to confront the ground realities of 1947, especially now, as the fourth and fifth generations emerge, each one further removed from the horrors of that time.

The postcards from the early 20th century go back into the colonial era. While visual manifestations of colonial propaganda sang loudly on the front side of the postcard, the back side hummed quietly with messages of love and remembrance written by the people of India.

“Due to contrasts like this, we can’t strictly categorise colonialism as black or white as is done in textbooks.”

The visuals of the postcards depicted undivided India through the lens of the British. An honest and raw window to the world of how the colonisers consumed India, the postcards captured Victorian architecture in India, devotional imagery, royal families, landscapes of cities and later on, everyday Indians as well.

A picture is worth a thousand words; the visuals in the postcards give us one of the clearest understandings of the British mindset. Kuppa explains that postcards were primarily consumed by the settled Britishers and elite Indians. The visuals of the land were used to show the British back in London, the “savage land and the natives that needed taming”.

One such correspondence was between a British officer’s wife, Eloise, and her uncle, Jane, in England. The postcards Eloise sent were of various parts of Calcutta, reflecting her own journey acquainting herself with the city.

Meanwhile, postcards with imagery of natives brought out the divisive ways the British had begun ethnographic and demographic surveys of India. The discriminatory class system can be studied through the postcards with portraits of royal Indian families, who were the patrons and the use of only certain religious devotional imagery.

Bansal says, “Colonialism was and remains a highly political time in our history. But what has failed to come to light, even via education, is that the lives of Indian’s went on. Despite dire political conditions, through the few personal accounts we have, we can, for once, represent the past as what it was actually experienced as.”

Subodh explains the colonial gaze, “History, which is written during the contemporary period, is also written from a particular perspective. In that context, when we talk about the British or European accounts and the native Indian accounts, the basic difference between the two is that for the British, it was a transfer of power, for Indians, it was a national movement or a freedom struggle.” He adds that this is the reason why the perspective or the methodology that is used by both sets of historians would not always match.

Microhistories challenge dominant narratives of history by focusing on the lives of those sidelined or overlooked. The microhistories of Partition live on in the memories of survivors whose trauma has too often been dismissed in history.

The Partition Museum was conceived in 2017 as a people’s museum―its 14 galleries are filled with artefacts donated by Partition families. Desai notes that these families are neither sad nor reluctant to part with such memorabilia. Instead, they come forward willingly, believing, “These reminders of our past belong here in the museum, with the rest of the narrative.”

“It’s a people’s story. The narrative has never been about the politicians or their beliefs,” says Desai. “Having the memory of the Partition presented to you in a tangible form is what makes the memory come alive. This collective memory of Partition families here at the museum is the whole authentic truth of what happened in 1947.”

Desai, in her mission to collect oral histories of Partition from those who survived it before it was too late, was met with deep trauma despite the willingness of people to recount the tale.

“One senior gentleman was a child during the violence. The women of his family decided to self-immolate to maintain their honour as violence struck their village. He recalls how, as a child, he somehow let go of his mother’s hand just as she jumped into the pyre and ran away. He was the only one of his family to survive,” Desai recounted. “Another man, while speaking to me, couldn’t stop crying as he remembered his life during the Partition, but he went on to tell his full story, for he said no one in his own family ever asked him about it, as it was too painful a memory to hear.”

“We don’t want our story to die with us,” a survivor told Desai.

Future generations have a lot more to lose if these stories die with the Partition generation, says Subodh.

“The impact of an ever-changing history on the youth is evident because they may not be aware of the actual truth,” he says. “What has been given to them as the ‘truth’ is taught as the absolute, unquestionable truth.”

“The next generation will not be inquisitive in nature, will not have an argumentative mind and will not be open to reason,” warns Subodh.

Purpose has driven what kind of history is written and distributed by the state. Subodh believes that it is up to society to be very careful and vigilant about what is consumed in history. Moreover, it is up to the people to choose what ‘truths’ to remember and which ones to forget.

Bansal, Desai, Kuppa, Subodh and even partition families, as keepers of history, all hold in common that a major facet of history lies in what has been kept out of the books: memory and personal accounts. In their collections, which are steadily growing, time has stood still and unwavering since 1947.