Louis Althusser, a French philosopher, proposed that schools are Ideological State Apparatuses (ISA) that function predominantly through ideology rather than violence. The recently released National Council of Educational Research & Training (NCERT) textbook of history for class 8 titled Exploring Society: India and Beyond is the latest example of the State’s ideological penetration through schools. The process that began with selective deletions of existing textbooks has found its culmination in the introduction of new textbooks that serve the agenda of the current political dispensation.

The textbook vilifies the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal dynasty as religious intolerants and labels their reigns as the ‘darker periods in history’. Even Akbar has been considered as a brutal emperor who destroyed temples and favoured Muslims in the higher echelons of his administration. This is the first time that Akbar, the Mughal emperor with a syncretic religious approach and advocacy of universal peace, has been described as bloodthirsty and considered responsible for ordering a massacre. The textbook fulfils an ideological agenda that has been in the pipeline for a while now. Additionally, what it also does is undermine a multiple perspective approach towards learning history, thereby discouraging divergent thought and critical examination.

The textbook undoes the developments that took place during the curriculum development exercise undertaken in 2005. The history textbooks developed under the aegis of the National Curriculum Framework 2005 focused on critical engagement with the past through a wide range of sources. The emphasis on history as a process, rather than a product, made it an exercise that was stimulating, engaging, and exciting. Students were familiarised with the methods of history writing at an early age rather than perceiving the textbook as a sacred text to be committed to memory. It was an attempt to make history an interesting discipline for learners who often get lost in the middle of pre-given sets of facts. The textbooks gave learners an opportunity to think and imagine the past with the help of primary sources.

Moreover, they embodied the idea of multiple pasts imagined from the perspectives of marginalised and subaltern groups such as women, tribes, peasants, and the oppressed castes. They gave a voice to those who had been invisibilised in the process of history writing. School history textbooks carrying these diverse perspectives were a milestone in the teaching and learning of history, wherein students could think, question, interpret and challenge. In spirit, these textbooks echoed historian E. H. Carr’s argument that history entails a continuous process of interaction between the historians and their facts.

The textbook fulfils an ideological agenda that has been in the pipeline for a while now. Additionally, what it also does is undermine a multiple perspective approach towards learning history.

The newly released NCERT textbook, however, undermines this spirit of multiplicity and interpretation by favouring one perspective of history. This perspective glorifies India’s achievements in the ancient past and portrays Muslim rulers as outsiders who ushered in a period of destruction and death. This narrative threatens to spark communal hatred, prejudice and bigotry amongst young minds and no cautionary note would be able to stop that. What is worrisome is the presentation of this version as the historical truth. There is no scope to think beyond what is given in the text or to familiarise oneself with different ways of interpreting the same source. A close-ended approach, coupled with the authority that textbooks carry in India, would bestow this version with the sacredness of the gospel of truth, dispelling any possibility of dialogue, debate, or discussion. Generations of young people would grow up learning about history as a singular narration with right and wrong versions.

The analysis by an American philosopher and educational reformer, John Dewey, holds relevance amidst the ongoing textbook politics. He contended that learning history provides an intellectual perspective to learners who cease to view things as happening in the moment and adopt larger perspectives. The purpose of studying history is to develop the abilities of students to view present and past events in the specific context of space and time. The latest history textbook threatens to reduce history to a set of facts to be recounted that may or may not be relevant to the everyday lives of learners. The feeling of alienation and disinterest that pervades history learning would continue unhindered.

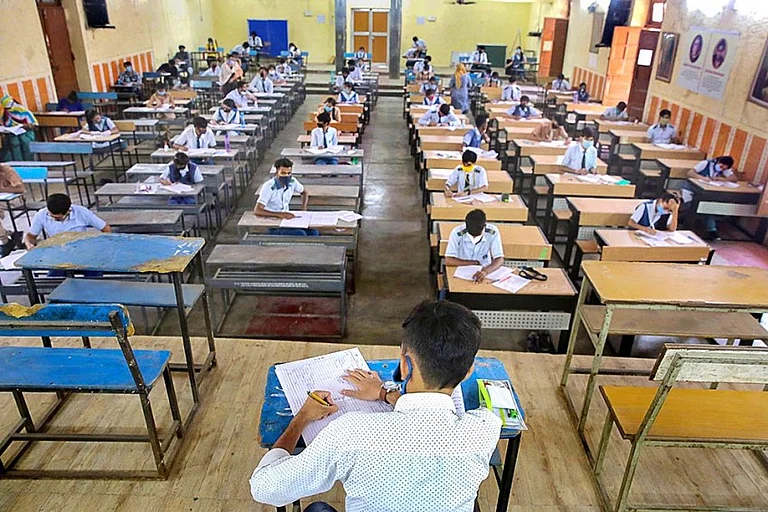

In this complex landscape, what could a history teacher do? An earnest teacher, who perceives history as being multi-perspectival, would find herself facing a difficult dilemma. She exists at the lowest rung of the decision-making hierarchy with limited curricular authority. When confronted with the strict syllabus timelines and pressure to produce perfect examination results, she could feel stuck in the face of this imposition.

Working in a textbook-examination nexus, in which textbooks must be taught and studied to ace examinations, her constrained decision-making could stifle her voice, autonomy and/or intellectual dignity. However, she must not lose hope or courage. Her pedagogical approaches offer her a significant avenue for resistance. She could open up diverse points of view in the classroom and offer a multi-dimensional view of history.

In the face of this ideological intrusion, teachers are the ray of hope who must challenge the exclusivist ideological narrative and resist with all their might. It is time for teachers to exercise their judgement in encouraging critical engagement, dialogue, and debate. After all, it is a teacher who can oppose ideological forces in the classroom and strive towards attaining the dream of a democratic education.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(Deepika Gupta is a research scholar at CA’ Foscari University Of Venice)

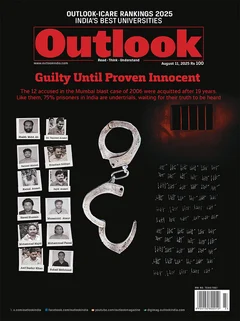

Outlook Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as 'The White Lies Mughals' in the magazine.