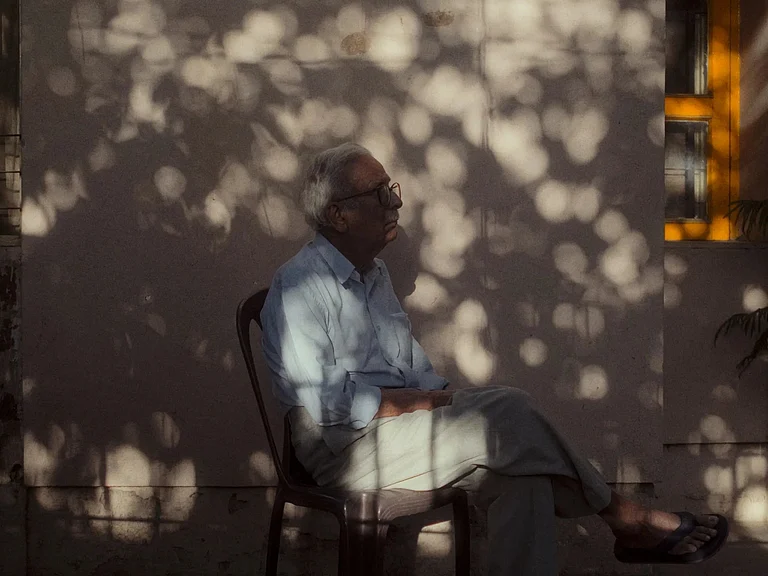

In the realm of Urdu literature, few individuals inspire as much fascination, admiration, and defiance as Jaun Elia. Jaun was a poet of existential anxiety, an analyst of desperation, and an aesthetic iconoclast, embodying and denouncing his era. His poetry did not merely transcend literary expression; he rather broke through the tradition with the finesse and then disdainfully rejected it.

Born Syed Hussain Sibt-e-Asghar Naqvi in western Uttar Pradesh’s Amroha in 1931, Jaun belonged to an illustrious family of intellectuals. His father, Shafiq Hasan Elia, was a poet and a scholar of Arabic, Persian and Hebrew, while his brothers also went on to achieve acclaim in literature and philosophy. Jaun was raised in an environment saturated with culture, knowledge, and political awareness. It is often said that by the age of five, Jaun had already started writing verses, and by 15, he was fluent in Arabic, Persian, and Hebrew.

Yet, despite this rare pedigree, Jaun’s life would be defined less by achievement than by estrangement.

The verses that Jaun wrote in the earlier part of his life reflect that his life was full of love and pleasure. It was primarily because of his beloved Fareha.

ہے محبت حیات کی لذّت

ورنہ کچھ لذّتِ حیات نہیں

کیا اجازت ہے ایک بات کہوں

وہ مگر خیر، کوئی بات نہیں

Translation:

(Love symbolises the essence of existence.

Life lacks essence otherwise.

Am I allowed to speak anything?

That, if, well, don't worry about it)

But everything changed in the blink of an eye; Jaun was still 18-years-old when the nation was divided in 1947, residents commenced relocating amidst violence and plunder, and residences became increasingly abandoned. Urban areas fell silent, as desolation commenced its movement across the vibrant streets and neighbourhoods. Silences commenced to protect the thriving squares. Jaun’s cherished Fareha migrated to Karachi and got married there. It left a profound mark on his tender heart. The depth of this emotional wound is clearly reflected in his poetry.

یہ مجھے چین کیوں نہیں آتا

ایک ہی شخص تھا جہاں میں، کیا؟

Translation:

(Why does a sense of peace continue to elude me?

Here was only one person in the world, was that all?)

A Poet In Exile Without Leaving Home

Jaun Elia migrated to Pakistan in 1957, 10 years after Partition. But this migration was not merely geographical. It was cultural, ideological, and deeply personal. He left behind not just a homeland, but also an entire intellectual ecosystem, the syncretic, cosmopolitan culture of north India. In Pakistan, he found a country still defining itself, culturally insecure, ideologically rigid, and increasingly religious. Jaun, a Nietzschean anarchist and avowed atheist, found himself alienated in this new, homogenising nationalism, this anxiety is quite evident in his poetry.

These verses reflect his alienation:

یہ مجھ سے ہو گیا کیا، کیوں اتنا بے قرار ہوں میں

کہ اپنی ہی وجود سے اکثر بیزار ہوں میں

Translation:

(What has happened to me, why am I so restless?

Often, I find myself displeased with my own existence)

This sense of exile without displacement became a defining theme in his poetry. His verses were steeped in metaphysical anguish, despairing love, and a kind of intellectual pessimism that made him both mesmerising and misunderstood.

I have heard from my friend who also happens to be from Amroha. He said once my grandfather was walking on the streets of Amroha, and to his sight came a person who was sticking to the walls, hugging and kissing them. At first, it looked like some lunatic to him, but then he asked him, “Who are you?” And the man replied, “Mujhe Jaun Elia Kehte hain” meaning my name is Jaun Elia. One can understand the depth of love Jaun had for his homeland.

On another occasion, Jaun was seen offering Salah (prayers), but his direction was not towards Kaaba, but towards another direction. Someone passing by asked him that Jaun why are you praying towards this direction and not towards Kaaba. Jaun replied: “Mera tou sab kuch Amroha mein hai”―meaning my everything is in Amroha.

Although these references can be weak in the historical senses, but one can have an idea of how much love he had for Amroha, the place of his birth.

The Philosopher-Poet

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Jaun’s poetry cannot be read purely through the lens of romanticism or classical Urdu traditions. He was profoundly influenced by European philosophy particularly existentialism. Nietzsche, Camus, and Marx are often cited as intellectual counterparts to his thematic explorations. His verses carry a philosophical density, laced with paradoxes, aphorisms, and rhetorical inversions.

Speaking about himself, Jaun once remarked in an interview:

میں ایک شاعر کم ہوں مجھے اس کا افسوس بھی نہیں ہے

میں ایک مترجم، فلسفی اور انکار کا مصنف ہوں

Translation:

(I am scarcely a poet, and I don’t even regret it. I am a translator, a philosopher, and an author of rejection.)

This intellectual honesty, this inability to perform, to pretend, defined both his life and art. He detested the performative nationalism and shallow religiosity that dominated Pakistan’s public sphere. Yet he never turned into a polemicist. His rebellion was internalised, aestheticised, and sublimated into his verse.

Elia’s ghazals delve into existential questions regarding human relationships, societal responsibilities, self-trust, and the inevitability of death (Shams, 2021). In one of his ghazals, titled “Naya Ik Rishta Paida Kyun Karein Hum” (Why do we create new relations?), which is also the first line of the ghazal, he questions the purpose of forming new relationships when separation is inevitable. This reflects a contemplation of the transient nature of human connections, suggesting a scepticism towards investing in bonds that may ultimately lead to conflict or separation. It also leads to a critical examination of our value on relationships and the emotional toll of their potential dissolution.

In the same ghazal, he further challenges the notion of societal obligations by questioning why individuals should care for a world that does not reciprocate concern. This reflects a sense of disillusionment with societal norms and expectations, urging readers to reconsider the significance of societal engagement and the nature of reciprocity in human interactions. It focuses on critical reflection and balancing individual needs and societal expectations (Nahi duniya ko jab parwah hamari, to fir duniya ki parwaah kyun karein hum). Translated, as when this world does not care for us, why should we care for this world?

Love, Loss, And Narcotic Longings

Much has been written about Jaun’s melancholia. But his grief was not theatrical; it was corrosive as well as consuming. He experienced love not as a sentimental flight, but as a wound that refused to clot. Despite his intellectual brilliance, Jaun Elia’s life was marked by deep personal sorrow.

His marriage to noted feminist Zahida Hina ended in divorce in 1992, further intensifying the recurring motifs of loss and estrangement in his poetry. He also grappled with addiction, financial difficulties, and deteriorating health. Yet, it was perhaps these very struggles that fuelled his artistic expression and gave his work its striking emotional depth. In this disappointment, he wrote:

محبت ایک شجر ہے جو کبھی پھل نہیں دیتا

(‘Love is a tree that never bears fruit.’)

He descended into alcoholism, becoming infamous for his dishevelled appearances, slurred recitations, and volatile public performances. Yet even in his intoxication, he remained deeply lucid. His speech was often more profound than the polished lectures of academics; his ruins more illuminating than others’ perfections.

Jaun’s addictions were not merely physical, they were metaphysical. He was addicted to meaning in a world rapidly losing its depth.

An extract from his poem: ‘Haalat-e haal Ke Sabab Haalat-e haal Hi Gayi’:

تیرا فراق جانے جان عیش تھا کیا میرے لیے

یعنی تیرے فراق میں خوب شراب پی گی

Translation:

(Was I meant to find joy in your absence, my love?

In truth, I numbed my sorrow with endless drinking while you were gone)

Despite having composed poetry since his teens, Jaun Elia did not publish a single collection until 1991, when Shayad was finally released. The delay was partly personal (he was a perfectionist) and partly systemic. The literary establishment, rooted in tradition and caution, did not know what to do with a poet who could rhyme “depression” with “repression” in a ghazal.

Jaun’s unique style led so many people to copy his style of reciting poetry, but miserably failed. For those, Jaun once remarked:

ہے اِک جبر، اتفاق نہیں

جون ہونا کوئی مذاق نہیں

Translation:

(It is a compulsion not coincidence, Being Jaun Elia isn’t a joke)

But when Shayad came out, it was nothing short of a literary earthquake. Readers, especially the young, found in Jaun a vocabulary for their own alienation. His cult following grew, spreading across borders, especially among Indian readers who saw in him the continuation of a lost, pre-Partition cultural soul.

The Cult Of Jaun

After his death in 2002, Jaun Elia’s reputation exploded. His verses were rediscovered on internet forums, YouTube recitations, and later, social media pages. Today, he is among the most quoted poets on Instagram, often shorn of context, misunderstood, or romanticised.

But even this diluted form of Jaun retains a strange power. His language, at once archaic and modern, dense and piercing, allows readers to project their own longings onto his work. Yet, to truly understand Jaun, is to look beyond the melancholy one-liners and enter the abyss he so willingly inhabited. It is to recognise him as a rare figure in South Asian letters, someone who neither sought validation nor feared oblivion. In this context Juan Eliya wrote:

تو میرا حوصلہ تو دیکھ داد تو دے کہ اب مجھے

شوق کمال بھی نہیں اور خوف زوال بھی نہیں

Translation

(Just look at how determined I am, no matter what:

I no longer want to be great or fear falling short)

Conclusion

In a literary culture that often demands conformity to form, faith, and nation, Jaun Elia stood out as a necessary heretic. He was a poet of refusal: of tidy categories, ideological binaries, and comforting illusions. His life was a slow-burning rebellion, and his poetry a record of that elegant undoing.

کیا سکہ چل گیا ہے کسے خبر میری

میں خود سے پوچھتا ہوں میں کون ہوں آخر

Translation: (What coin has passed for value, who even knows of me? I ask myself again and again who am I, after all?)

In the present period, as Urdu experiences a decline in its country of origin, individuals, particularly the younger generations in India and throughout the subcontinent, continue to be drawn to the Urdu language. Juan Elia’s poetry serves as a catalyst for reconnecting individuals with the fading voice of Urdu, which once flourished throughout South Asia.

(The author is Research Scholar, Department of History and Culture, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi)