Summary of this article

A photo-essay tracing the forgotten migration of women indentured labourers from north India to Suriname through colonial contracts and family memory.

Centred on Dhannu Munia, a Bhojpuri woman migrant, the work explores gender, displacement, and erased histories under colonial labour systems.

The project confronts the absence of memory in present-day villages while reclaiming ancestry through photographs, archives, and oral testimony.

This photo-essay looks into the lost memory of migration connected to women indentured labourers from north India, who migrated to the Caribbean, Suriname and Mauritius in the nineteenth century. Indentured migration from India to Suriname took place around 1873 when famine and droughts heavily affected parts of the northern Indian region. After the abolishment of slavery by the Dutch government in 1863, indentured labourers were required in Suriname. The ancestors and places described in this research are from the emigration contracts that mentioned villages of migration based in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

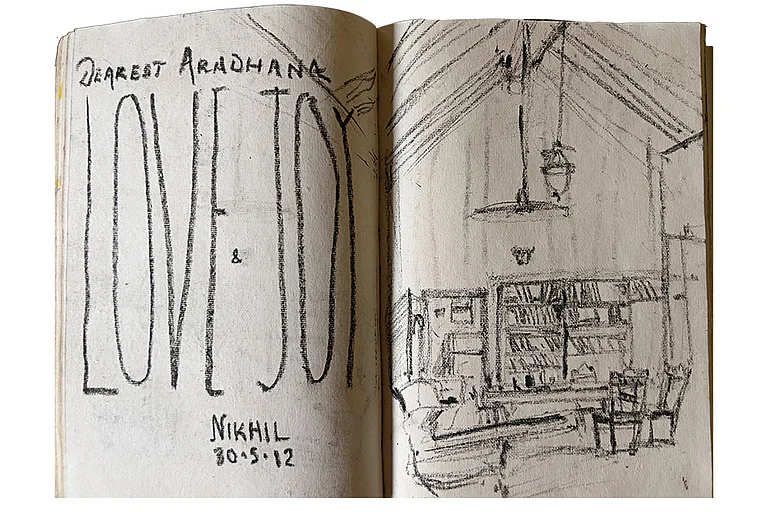

Tracing villages is done with a focus on indentured labour contracts found in the National Archives of Suriname. The exploration of migration in present villages in India starts with the indentured labour contract of Dhannu Munia, who is a first-generation family member who migrated from Uttar Pradesh to Suriname. I have attempted to find out more about the current memory of migration and the traces of visual culture related to the identity of my ancestors and imagining the place of departure.

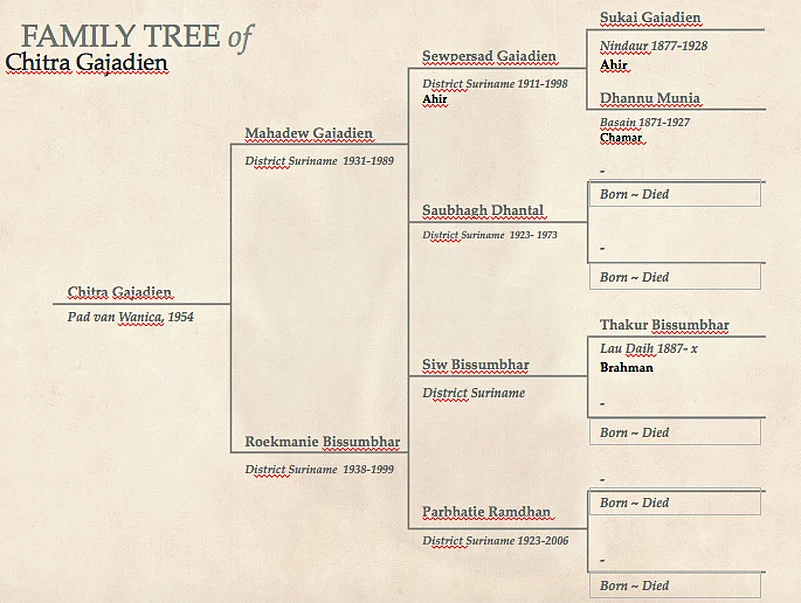

I refer to my own family lineage, which consists of descendants of Bhojpuri migrants, as described in my mother Chitra Gajadien’s oral testimony—A Silenced History. It talks about the migration of Indians to Suriname and their second migration to the Netherlands. I created a collection of photographs that are published in a book titled Kahe Gaile Bides (Why did you go overseas?)

In January, I walked into the premises on the Lachmisinghweg where the Gajadiens live. The ninety-five-year-old Sewrattan was not used to conversing with a woman, and certainly not with a family member who had lived in the Netherlands for thirty years. I wanted to know, by all means, where the graves of my great-grandfather and great-grandmother were. They had been buried in the compound of their house, but where exactly? A stately gesture in the direction of the mango tree—“somewhere over there”.

My ancestors wanted to have rice, dal, potato, sugar and some other items, part of the Hindu puja samagri (ingredients for a religious ceremony). If I did not offer all that in streaming water, it would not be good for me. I got scared and immediately did what I was asked to do. This offering, meant for people dead for more than eighty years, what sense did it make? Later, I began to worry more and more about my ancestors. What did they really want from me? (Chitra Gajadien, 2005, p. 23)

I wanted to trace my ancestor, Dhannu. Who was this woman? What did it mean to be a female indentured labourer making the journey from India to Suriname? The indentured contract of Dhannu formed the primary source to imagine her village of migration in India. I have reimagined the journey of Dhannu. Since she was a woman, and migrated as an indentured labourer, imagining her journey would be in contrast to the patriarchy that is deeply rooted in the village community. I asked: What is the current sense of memory of migration in these villages and if there is a remaining awareness of a bond between the villages in India with those in Suriname?

One can imagine how Dhannu would have experienced the train journey from her village to Calcutta, perhaps with a feeling of unimaginable fear laced with anticipation. She might never have boarded a train before or spent a night alone in an unfamiliar surrounding without her husband. She left her village, Basain, with her son for a reason that remains unknown; it has not been described in the contracts of indentured labour. The reasons people chose to leave were of no importance to the colonial administration and thus, this was not recorded. Dhannu and her son boarded a train that would not have the speed of today’s trains and it must have taken a lot more time to reach the migrant depot at Calcutta. What would this passage of time mean for the migrants? What would her thoughts be while looking through the window of the train at the different landscapes affected by drought that passed by?

Dhannu was recruited and seems to have given her consent on a contract based on the contract for females in Mauritius. When one observes the colonial contract for women in Mauritius, the focus was on the father’s name, marital status and wages. The difference between Mauritius and Suriname was that the labour contract was not for one year but for five years. We do not know if this was under duress. This is not indicated in the documents of indentured labour. In some cases, the consent was voluntary. In other cases, it was not. Often, recruiters created a false idea about Suriname, as they received money for every person that they persuaded to migrate. The recruits were partly misled by evoking Suriname as the country of Sri Ram.

I could not find the traces of my family members in the individual memories in the respective villages. Imagining Dhannu’s journey and her village is the only residue that is left for me.

How would Dhannu answer the questionnaire of the colonial government for the establishment of the contract of indentured labour? Would they have asked her about her husband and the reason why she was travelling alone with her son? Or would she have been abducted because the arkathiyas (recruiters, East Indian Middlemen) needed more women to migrate overseas? Abduction was a phenomenon that appeared and the laws and treatment for the arkathiyas had to be amended several times. The contract did not reveal any detailed information about the working conditions in the destination colony. This meant that Dhannu, like all indentured labourers, was left without sufficient information about the destination of the ship journey that would take three months.

When I consider the situation of Dhannu, I wonder if this young woman, who was 24 when she left, had learned how to write. Like most women then, she was most probably illiterate. She started off by working on Plantation Meerzorg and was later transferred to Plantation Marienburg. We can assume she had no ability to write home and furthermore, took her child with her on the ship journey to Suriname. There could have been a letter-writing facility in the destination colony; this was often the case in villages in India and someone could write on behalf of a person.

Since it was difficult for elderly people to memorise their daily life and objects from the villages they left behind in India, such as water wells that surround them in their own village, memories of migration must have taken the form of abstraction and disconnection from their past. Enforced by the loss of the tradition of artisans to capture or orally document specific memories, it becomes harder for people to understand their own community. Six generations have existed since the time people first migrated to the current generation. The stories of pain and void left behind by their loved ones seem untraceable in the villages.

I could not find the traces of my family members in the individual memories in the respective villages. Imagining Dhannu’s journey and her village is the only residue that is left for me. In the abstraction of my thought, besides the fact that I never found her village, there is a stark contrast with the village Nindaur in Ara district of Bihar of her husband, Sukai Gajadien, captured in three photographs. Her story remains untold, yet part of my daily experience of longing for the unknown is integrated with my identity and perception of who I am.

Sarojini Lewis has a background in Fine Art with a specialisation in archival photography, video art and book arts. She is currently working as a curator, researcher and artist.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

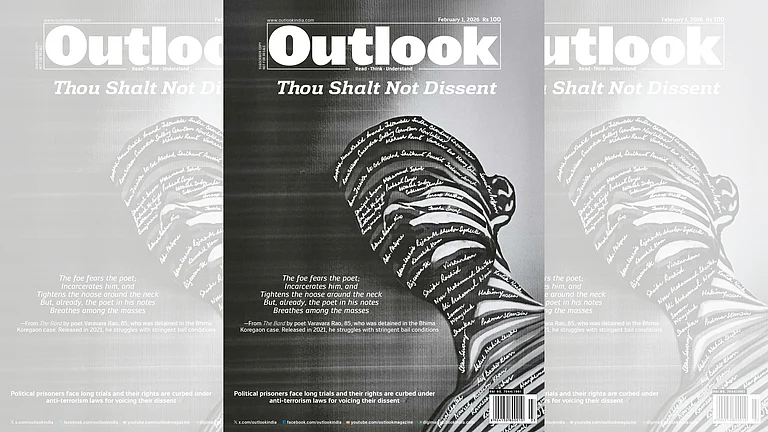

This article appeared as Tracing The Memory Of Migration in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘Party is Elsewhere’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.