Summary of this article

The people who were protesting the discriminatory citizenship laws, many of them young, several of them women, ended up in prison.

A thuggish chief minister warned that anyone who said there were no oxygen tanks available would be arrested.

You notice one fine day that all signs on the road have changed. Your town has a new name.

I am concerned with the landscape of memory. Do you remember how the night-sky glowed with funeral fires? I read reports that the metal in the crematoriums was melting. You were walking among the dead. A thuggish chief minister warned that anyone who said there were no oxygen tanks available would be arrested. There were so many bodies floating in the Ganga and dogs were sticking their snouts into corpses buried in shallow graves on the river’s banks.

But you know how it is. In one season, you have seen the branches of the trees heavy with fruit, and you cannot recall that distant season when the branches were bare. When the next elections came around, how many remembered what it had been like during those times? The same man who had lied about oxygen tanks went around proclaiming the victory of his party. Why do we let this happen? It is perhaps because we surrender to spectacle. And we are seduced by sentiment. We choose to uphold the constitutionality of the irrational.

The guy on the throne, the toast-master of all tamashas, decided to shower rose petals from helicopters to honour the medical staff. All that while, there were millions on the highways trying to get home, to Ballia and Bettiah, and Sitamarhi and Siwan. This is the landscape of the nation-state: hills and valleys. One group, blissful in its comfortable ignorance, sits on the mountain-top while the masses trudge along the snaking paths in the valley below.

We cannot go on spreading the poison of hate. Violence is endlessly recyclable. Stop torture. Stop bulldozer injustice. Remember that we live in one world. Remember that the body forgets nothing, nor does the earth.

A memory is coming back to me. Some of the Bihari workers trying to return home during lockdown thought it was a good idea to just follow the rail tracks, even if it meant trekking hundreds of kilometres. There were no trains running. If they kept walking along the railway lines, eventually they would get home. When night fell, they too fell down, bone-tired, and slept on the tracks. I know you are now remembering all this too. A goods train came out of the night and crushed a group of them. The news report said that what lay scattered on the tracks were several rotis and a rubber chappal stained red. There you have it. A solitary chappal narrating a story of a hasty exit—not from a glitzy ball, like fair Cinderella, but from life itself. What do I make of the landscape where a ghost train has passed leaving behind a red chappal? To me it is the accurate map of a country that thumps its 56-inch chest and makes noises about its rising GDP that will soon overtake Japan, that country with really fast trains.

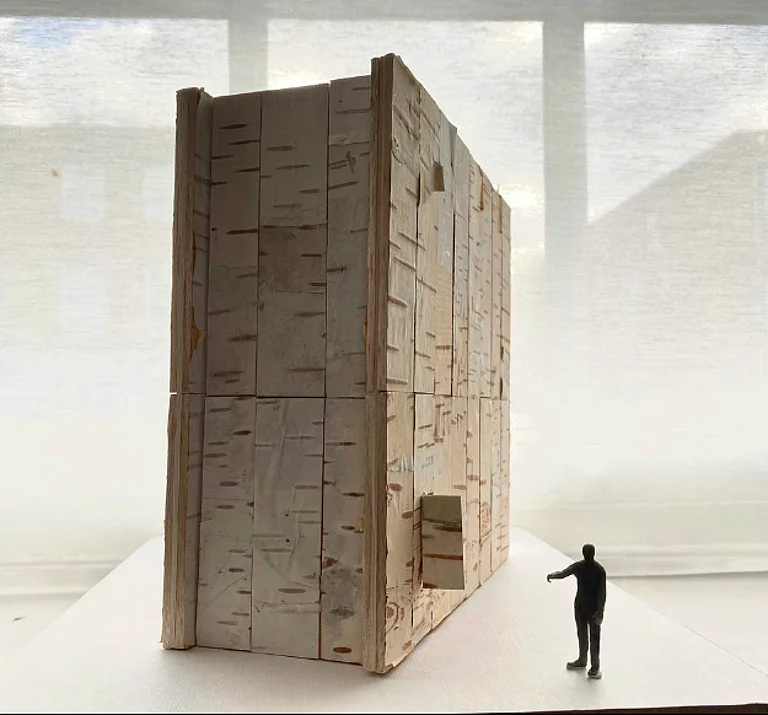

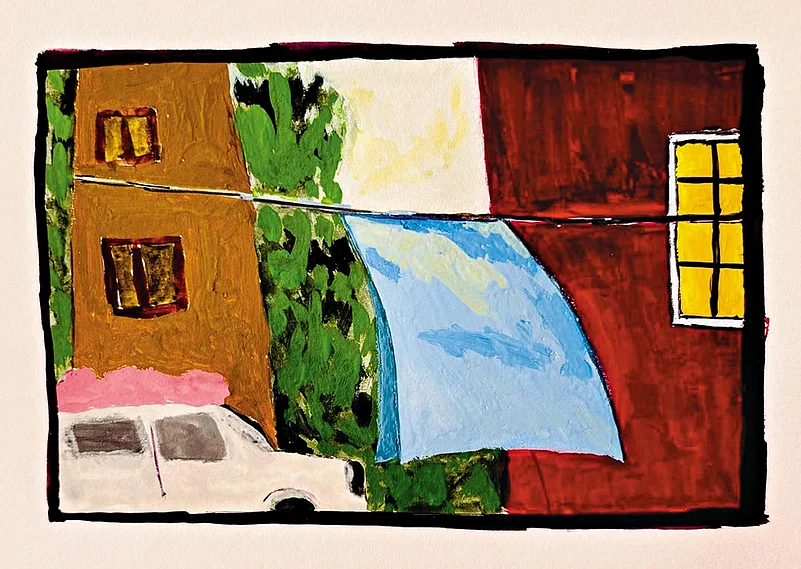

So much of our social landscape is imagined. Look at the above drawing of mine. I made it after the Delhi riots of 2020. It was my way of remembering Bashir Badr’s immortal lines: ‘Log toot jaate hain ek ghar banana mein/Tum taras nahin khaate bastiyan jalaane mein’ (People go broke in building a home/And you remain unmoved as you burn neighbourhoods). The poet’s own home had been gutted in the Meerut riots in 1987. As I look at the drawing, I am trying to remember the names of those who remain in jail today. There are so many names to remember. The people who were protesting the discriminatory citizenship laws, many of them young, several of them women, ended up in prison. They inhabit the landscape hidden from view: the prison which is the space where protesters are condemned to spend their days without trial. I cannot remember the name of the politician who was filmed inciting the riots. What happened to him? Did he go to prison? No? He became a minister instead? You don’t say! I should have remembered his name. I know now why my cowardly heart has chosen to forget.

All through the pandemic, I was fearful that my father would die of the COVID coronavirus. I breathed more easily once he got vaccinated. But the pandemic, its enforced social isolation, had weakened him and he died after a brief illness in early 2023. In a novel I was finishing at that time, a man from Champaran, the same age as my father, draws a map of his remembered village. The map that the man ends up drawing is obsolete, it represents the village at it was in the man’s childhood. He is unable to meet the present. He is defenseless against history. The truth is that writers, even when they are writing fiction, are sketching maps of what they recognise as threats. In an earlier novel, my protagonist delivers the following riff: ‘Why must one slow-jam the news? Because all that is new will become normal with astonishing speed. You will go to visit your father and discover that he has pledged himself to the Great Leader. Or you will visit your friend’s house and it will take a minute or more to realise that a meeting is underway and now everyone is looking at you with suspicion. You notice one fine day that all signs on the road have changed. Your town has a new name. Dogs have grown fat on flesh torn from corpses lining the street where you grew up. The beautiful tree outside your window is dead, it has been dead for some time, and has, in fact, just now burst into flames.’

Sab yaad rakha jayega, sab kuch yaad rakha jayega, wrote the poet and performer, Aamir Aziz. Everything will be remembered, nothing will be forgotten.

I remember the sea. I was driving in a car on a highway near the Konkani coast and caught a glimpse of it between the buildings: the sea was like a blue sheet hung on a clothesline. Tired as I was after hours of travel, that fleeting sight offered relief. How wonderful it would have been to wade into the waters.

Why didn’t I stop? I was in a hurry, going to interview a Muslim family—they had been tortured because it was thought they had a grenade launcher in their home. It turned out it was a piece of textile equipment. Over the years, I have often thought of the sea I had seen but for a moment. How beautiful and beckoning it was. And will remain so, unless we poison it with plastic. The same, of course, goes for our country. We cannot go on spreading the poison of hate. Violence is endlessly recyclable. Stop torture. Stop bulldozer injustice. Remember that we live in one world. Remember that the body forgets nothing, nor does the earth.

Amitava Kumar is a writer and artist who is Professor of English at Vassar College in upstate New York

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared as ‘Sab yaad rakha jayega’ in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘Party is Elsewhere’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.