Summary of this article

The text links human desire to performance and imagination—a longing for an “elsewhere” that exists both internally and externally, where fiction blurs the boundary between reality and possibility.

Through the film A Breath Held Long, Mumbai emerges as an agitated, inescapable presence, where silence is impossible and breath becomes politicised, shaped by urban noise, movement, and time.

Breath and voice function as acts of resistance and survival; identity is expressed not through representation but through sustained utterance, endurance, and the fragile act of listening within collective flux.

The human instinct to act or perform in the world must be deeply connected to the idea of desire. A desire to be elsewhere. The elsewhere place, fuelled by an urge to bridge the gap between what is and what could be, can be both within and without. It could be located in a private cosmos, where the mind performs without a physical trace—it is a possibility for ‘fiction’ to be realised and to narrow the distinction between what is real and what is not. That’s the territory or non-territory in my film A Breath Held Long, which refers to many imagined territories that point to various personal states within one’s subjective universe and explore the intersection between voice, body and the city and the act of breathing as a metaphor for life within an urban landscape. Shot on 16mm celluloid, the camera’s mostly still gaze contrasts restless character of the city in motion. This stillness suggests a presence within the great urban flux. The camera becomes a site of listening and holds the tension between the worldly and the intimate, between the impulse to pause and the relentless enactment of time. Set against the backdrop of Mumbai, the narrative acknowledges the impossibility of silence within the city. The urban atmosphere, agitated and continuous, seeps into almost every frame. Noise of the city refuses relegation to the background. It ultimately reflects on the conditions of contemporary breath—its rhythm, its politicisation within an urban setting. It considers what it means to hold breath in a city that never ceases to move, to pause within motion without disengaging from it. The work is about listening—listening as resistance, a fragile act of being truly alive. It becomes part of the fabric of a non-linear narrative that collapses the boundary between the city’s collective roar and the performer’s internal state of being.

Within this flux, each performer locates themselves through an act of physical negotiation with breath. Their voices carry individual inflections and hesitations, producing a collective and yet uneven texture. Identity, here, is not performed through representation but through endurance—the act of sustained utterance within the limits imposed by time. Speech emerges as a form of resilience: to breathe within the city’s relentless tempo is itself to mark a space of presence.

Performances of a group of actors and singers from Mumbai unfold through a series of single-line narratives and music. The lines, without punctuation, that speak of short personal events within the city, demand of awareness of breath as a temporal medium. All of the lines are recited as a third-person account of an event each; the performer must situate themselves within the “elsewhere”—the unique time and place evoked by each narrative.

The acts of breathing in and out become compositional devices—intervals through which rhythm and exhaustion surface as material conditions for speaking and being. A space for them to play out the stories in a way to make them their own. A breath is that liminal space, the one that takes us from one moment to another.

The had grown so thin that he was a little too bony than I would have liked to know of his body and his saliva was seeping into his last hospital pillow long after he was gone like a ritual for the last months of his life when he was trying to sleep induced by drugs with unpronounceable names as difficult as some of the names of the mythological characters he would tell stories about that we found hard to remember and now we could only spend rest of our lives remembering some of the simpler things about him like the way he combed his hair in front of the mirror every morning before he left for a stroll with his younger friends in a middle-class Maharashtrian neighbourhood with many hues and a touch here and there of people from other regions who rolled themselves towards a washed and yet obscurely stained white sheet of the small city lake they circled around like one that the pair of nurses from Kerala changed every morning at the hospital rolling his six foot long body first to the left and then to right and again to the left and to the right as they pulled out the old sheet and slipped the new one under his unyielding body before sponging it wet and then dry in such practiced manoeuvres that only matched his facility with words that he put to use while talking and arguing with the doctor who made his customary visit late mornings with a smile that hardly seem to vary even long after he was on his way home after the day’s work and somehow seemed to reappear on his face as he entered the hospital every morning like his patients desire to live hardly ever vary till the last night of incessant screams before the morning of his passing with the hospital window wide open on a breezeless winter day during the peak hour traffic sounds that drowned the sounds of any possible sobs of his wife or of his middle aged daughters in their unanticipated bright cotton saris as we waited for others to arrive

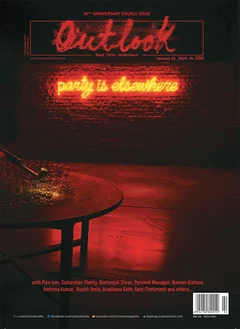

This article appeared as "A Breathe Held Long” in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘Party is Elsewhere’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Sudarshan Shetty explores the fundamental ontology of objects through sculpture, drawing, and installation. His practice engages with the poetics of impermanence, transition, and the layered meanings embedded within material culture. Drawing on both individual and collective memory, Shetty proposes multiple narratives that reflect on the cultural, emotional, and philosophical significance of structures and objects