Trend of replacing fact with fiction has become increasingly apparent over the past decade.

How should one proceed in this context? Adhering strictly to the textbook may compromise professional judgement and expertise.

Political regimes may change, but if the institutional memory of historical scholarship is actively preserved, it can endure beyond transient circumstances

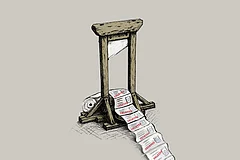

The revision of history textbooks is a continuous process. It involves more than simply adding new information or omitting material that may be considered inconvenient. Historically, the discipline of history has often served as a tool for political interests. In both scenarios, it is fundamentally about interpreting facts. Concerns arise when historical revision occurs not due to the discovery of new evidence or the introduction of fresh interpretations, but rather as an attempt to remove, minimise, or distort established facts in favour of subjective perspectives.

This trend of replacing fact with fiction has become increasingly apparent over the past decade. This situation is significantly impacting the integrity of educational institutions adopting the new textbooks, as well as affecting the morale of the faculty responsible for teaching them. The presence of the National Council of Educational Research & Training’s (NCERT) imprint on a textbook, once regarded as a sign of credibility, is increasingly met with scepticism. Repeated instances of distortion diminish the authority of such institutional endorsements, thereby undermining confidence not only in school-level education, but also within Indian academia more broadly. Moreover, this situation presents a significant challenge for educators who have been trained to approach history as a discipline rooted in causality, analysis, and evidence. Teachers now face the expectation to present fictionalised accounts as factual, potentially misrepresenting certain groups, overlooking others, or omitting entire historical events.

The question arises: how should one proceed in this context? Adhering strictly to the textbook may compromise professional judgement and expertise. At present, there is a noticeable increase in self-censorship, silence, and ethical challenges within the field. Many educators focus on preparing students for examinations, often excluding comprehensive and accurate knowledge from classroom discussions.

Those who strive to uphold academic standards may find themselves at odds with institutional expectations, potentially facing disciplinary actions. To be an educator involves not only imparting knowledge, but also fostering values such as honesty, curiosity, a commitment to truth, and integrity among students. When educators are required to repeat narratives known to be inaccurate, this can result in ethical concerns for future citizens. Increasingly, classrooms are moving away from encouraging critical thinking and instead risk promoting conformity. If these trends continue, they may similarly affect higher education, where unsupported narratives might take precedence over thorough historical analysis.

Educational institutions derive their authority fundamentally from trust rather than coercion. Individuals pursue studies, or encourage others to do so, in order to advance knowledge and seek truth. The study of history is intended to clarify how societies have reached their current state and to inform future directions based on prior experiences. In this sense, history serves to guide us toward a better future, rather than simply celebrating the past. Institutions receive funding because there is confidence in their ability to generate valuable knowledge.

When falsehoods are presented as historical fact, educational materials that should convey truth instead become vehicles for ideological indoctrination, eroding trust. Such research is frequently dismissed as political, and once this becomes widely recognised, international partnerships may diminish and funding can become increasingly difficult to justify. Respected universities of the past may now be seen as unreliable, causing reputational harm that extends beyond historians to other scientific and academic fields.

One should not forget that India has had a proud tradition of historical research, built painstakingly over decades by our scholars committed to rigour and objectivity. We have travelled a long way from colonial history writing bequeathed to us by colonial writers like James Mill and others. History during the 19th century, which developed under the influence of our colonial masters, down to the first half of the 20th century was individual-centric, with epochs divided on the basis of reigns of individual rulers.

Religion of the ruler was taken as the marker. But then from 1960s, researches conducted by Indian scholars helped shift the attention from rulers and their religions to other factors agrarian conditions, class studies and social development. Scholars like D D Kosambi, R. S. Sharma, Mohammad Habib, Romila Thapar, Irfan Habib, D. N. Jha, R. C. Majumdar, A. D. Pusalker, H. D. Sankalia, and S. K. Chatterjee helped change the narrative and our knowledge of the past. These included ‘nationalists’—Left and Right historians. By 2000 AD, the trend further changed in the face of further researches and from the study of elites and ‘ruling classes’—attention now shifted to the ‘middle classes’ and people's history.

The re-writing of textbooks negates all this development of the last 70-80 years. We are being taken back to-and-from where we started.

The re-writing of textbooks, which is now taking place, negates all this development of the last 70-80 years. We are being taken back to-and-from where we started. In fact, there is a further push backwards, with emphasis shifting to religion and selective presentation. If a bilingual coin was struck during the 10th century emphasising harmony between Hinduism and Islam—but as it doesn’t suit the narrative of the authorities, re-writing textbooks—it is ignored. A similar, but much-diluted effort of the same kind, undertaken by a king of “acceptable” religious denomination is instead highlighted. The "temple destruction” by a particular set of rulers is highlighted as if nothing else took place in Indian history since the 13th century, but similar acts by rulers of a different religion is totally suppressed. Nay, one re-written textbook glosses over all temple destructions caused by Marathas during their raids in north India, and students are instead told that the Maratha rule “preserved temples and educational institutions. Great women who contributed a lot—Razia Sultan, Nur Jahan, Jahanara and a host of others—are ignored, but “mighty Maratha women” like Tarabai and Ahilyabai find mention. At one place, the fact that both Iqta (under Delhi Sultans) and Jagir (under Mughals) were non-hereditary and transferrable is glossed over. Instead, students are told that transferability and non-hereditary character was actually achieved under the Marathas. What is the message that is being conveyed? Imagine the harm to the Indian psyche it is going to cause.

The challenges facing scholars and institutions are considerable. It is essential to uphold institutional autonomy and promptly replace any distorted syllabi or textbooks. Remaining silent is not a viable choice; although it may seem prudent in the short-term, it ultimately leads to long-term irrelevance. Political regimes may change, but if the institutional memory of historical scholarship is actively preserved, it can endure beyond transient circumstances. Failing to do so risks not only the loss of history itself but also undermines the pursuit of truth within public life and national discourse.

(Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi Is professor of history, Aligarh Muslim University, And secretary, Indian History Congress)

Democracy is about ballots, but also about memory—who safeguards both, and who seeks to rewrite them? Outlook’s September 11, 2025 issue, 'Election Omission' probes these erasures—of voters, voices, and histories—asking what they mean for India’s democratic future. This article appeared in print as 'Staking Claim to the First Spot'.