Some Mahadevapura residents say they were relieved that the issue they had long been struggling with—voter enrolment and deletions—had finally made headlines in the national media.

Congress leaders who campaigned intensively in Mahadevapura during the 2024 General Election share similar misgivings.

Mahadevapura Lok Sabha constituency was carved out in 2009, the BJP has consistently held the seat

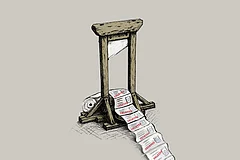

Mahadevapura, the Karnataka Assembly constituency that became the epicentre of Congress leader Rahul Gandhi’s “vote chori” (vote theft) allegations, now wears a quiet look. The flurry of media personnel and political leaders who had descended on this fast-growing Bengaluru suburb marked by a high migrant population and rapid urbanisation has since retreated, leaving behind a calm that contrasts sharply with the recent political storm in which Mahadevapura shot into the national spotlight after the leader of the Opposition alleged that “vote chori” in this assembly segment enabled the BJP to bag the Bengaluru Central seat in the 2024 Lok Sabha polls.

Claiming 1,00,250 fake voters were illegally added to the electoral rolls, Gandhi accused the ruling party of engineering the fraud using five methods—duplicate entries, bogus and invalid addresses, large numbers of voters registered at a single address, ineligible names and misuse of Form 6. He argued that the alleged manipulation of the rolls tilted the balance in favour of the BJP in what was otherwise a closely fought contest.

Residents in several parts of Mahadevapura constituency say problems concerning voter registration recur with every election, including allegations of both arbitrary deletions and mass rejections of applications. “We have faced issues with the voters’ list for years,” says Ramesh, a long-time resident in Whitefield, one of the fastest-growing neighbourhoods in the constituency. “Many applications were rejected without explanation.”

Other residents recall that the problem first came to the fore during the 2018 Assembly election and resurfaced in the 2023 polls, leaving thousands without voting rights despite repeated attempts to register. In fact, voter turnout in Mahadevapura has consistently lagged behind the state average. For instance, in the 2014 Lok Sabha election, Bengaluru Central—of which Mahadevapura is a part—recorded just 55.63 per cent turnout, one of the lowest in Karnataka. The figures raised concerns that eligible voters were being left out of the rolls in this zone of high migration and rapid urbanisation.

Residents in several parts of Mahadevapura constituency say problems concerning voter registration recur with every election.

The growing discontent pushed citizen groups to intervene. One of the most prominent efforts was the Million Voters Rising campaign launched in Whitefield in 2016. Local residents, civic activists and volunteers came together to run awareness drives and assist people—especially migrants, IT workers and industrial employees—in applying for voter enrolment. Similar initiatives soon spread to other parts of the constituency.

The results, activists say, were disheartening, however. “More than 65 per cent of the enrolment applications from 2014 to 2018 were rejected, many without any reason given,” recalls an organiser of the Million Voters Rising campaign. According to residents, entire groups of applications submitted collectively by apartments, RWAs (Resident Welfare Associations) and civil society groups were struck down, often with no official explanation.

Allegations of voter deletion—where names of existing voters were mysteriously removed from the rolls—also added to the anger. In several cases, families found the names of their members who had voted in previous elections missing from the rolls on polling day. For many in Whitefield and neighbouring localities, the combination of mass rejections and deletions comprised what activists describe as a “systematic denial” of voting rights in Mahadevapura.

“Despite the chief electoral officer Sanjiv Kumar ordering a re-scrutiny of the rejected applications—and even after some residents approached the High Court of Karnataka in Bengaluru—the issue of faulty voter enrolment in Mahadevapura remained unresolved,” says Adith, a resident. Nearly 3,000 applications were rejected before the 2019 Lok Sabha polls alone, estimate activists associated with the Million Voters Rising campaign.

The situation deteriorated in the run-up to the 2023 Assembly election. According to Congress MLA Rizwan Arshad, members of an NGO—Chilume Educational, Cultural and Rural Development Trust—were illegally issued identity cards meant for Booth Level Officers (BLOs). Armed with these credentials, he alleged, the NGO carried out mass-scale additions and deletions of voters’ names. “Chilume had close connections with the BJP leadership and was acting on their behalf,” Arshad claims. Though the Election Commission had officially tasked the NGO with executing the Systematic Voters’ Education and Electoral Participation (SVEEP) campaign, the Congress alleged that Chilume was simultaneously running a parallel political consultancy that assisted the BJP during elections.

Arshad claims his party’s persistent complaints forced scrutiny before the 2023 polls. “Our allegations were vindicated when it was proven that some Election Commission officials had colluded with the NGO, and some of the officers were suspended. If we hadn’t exposed the fraud, we would have lost the 2023 election,” he says.

Some Mahadevapura residents say they were relieved that the issue they had long been struggling with—voter enrolment and deletions—had finally made headlines in the national media. Yet, there is also a sense of scepticism. Many fear the heavy politicisation of the controversy could pre-empt any real corrective measures on the ground.

Congress leaders who campaigned intensively in Mahadevapura during the 2024 General Election share similar misgivings. They point to what they describe as a sharp disconnect between the visible anti-incumbency in the area and the eventual outcome. “There was much discontent against the BJP in Mahadevapura, and we were confident it would reflect in the results,” says Jiby John, secretary of the Karnataka Pradesh Congress Committee (KPCC). The Congress, he recalls, had gone into the contest with high expectations. “We were hoping to win the Bengaluru Central Lok Sabha seat. We ran an extensive campaign, strengthened our organisational machinery, and the substantial minority vote share gave us additional confidence,” he adds.

Since the Bengaluru Central Lok Sabha constituency was carved out in 2009, the BJP has consistently held the seat. In the 2023 Assembly election, however, the Congress managed to win five of the eight assembly segments in the parliamentary constituency—a performance that gave wings to the grand old party’s hopes.

“Everything was going according to plan, and even the early counting trends supported our expectation,” KPCC secretary John recalls. “But once the votes from Mahadevapura were tallied, there was a sudden, unbelievable shift towards the BJP. That was when our doubts grew stronger.” MLA Arshad says the Congress candidate Mansoor Ali Khan drew the attention of the party’s national leadership to Mahadevapura. “Following the direction of the national leadership, we constituted a committee of experts and data analysts. In the initial analysis, we found discrepancies. Our team then made an extensive investigation for more than six months and unravelled how the Election Commission connived with the BJP to sabotage the democratic process,” Arshad claims.

In fact, ever since Mahadevapura was carved out of the erstwhile Varathur constituency along with KR Pura and reserved for the Scheduled Castes, the constituency has been represented by the BJP. In 2023, the incumbent BJP MLA Aravind Limbavalli was denied the Mahadevapura ticket due to internal rivalry in the saffron party. The ticket was given to his wife, Manjula, as a compromise. The Congress was hoping to capitalise on the internal dissent in the BJP but Manjula won by over 44,000 votes.

Today, even though Rahul used Mahadevapura as an example to launch the campaign against alleged vote chori, the BJP in Karnataka stands unfazed. In fact, BJP MLA Aswanth Narayan, a former minister, openly admits there could be some discrepancies in the voters’ list. “The Mahadevapura constituency includes many places like Whitefield where a significant number of migrants live,” says Narayan. “So, there are chances of discrepancies in the electoral rolls, many of which can be identified and corrected well before the election. The Congress, which took no action nor filed any case after the results were in, is now blaming the system. This reveals their political impropriety, and will further alienate them from the voters.”

Alleging that dissidents are routinely sidelined in the Congress, the BJP MLA cites as a “telling example” the case of K.N. Rajanna, who was “stripped of his ministerial berth after raising uncomfortable questions”. Rajanna, who served as the minister of cooperation and was a close confidante of Chief Minister Siddaramaiah, was removed from his ministerial post after openly challenging Rahul’s vote chori claims and his attempts to blame the Election Commission. Though he offered to resign, Siddaramaiah expelled him from the cabinet following instructions from the Congress high command.

K.V.S. Namboodiri, a Bengaluru-based senior journalist and political analyst, argues that large-scale irregularities in Mahadevapura’s electoral rolls did not begin with the last General Election but much earlier. “Between 2008 and 2024, the electorate in Mahadevapura grew by nearly 150 per cent, while most other urban constituencies in Bengaluru registered only a 10–25 per cent increase,” he says. “Now, we cannot conclusively say this abnormal growth is entirely due to fraudulent practices as this period also coincides with Mahadevapura’s transformation into a real estate hub and an industrial corridor, which naturally attracted a huge influx of residents.”

Some argue Rahul’s vote chori thrust may push the Election Commission towards a scientific revision of the electoral rolls. Whether this exercise will address the long-standing concerns in constituencies like Mahadevapura, however, remains to be seen. What is clear is that electoral rolls have become a political battleground in Karnataka, with parties devoting unusual attention to additions, deletions and revisions ahead of every poll. The real test of the fallout from these allegations may not come immediately, but during the Bengaluru Municipal Corporation election in 2026, when the accuracy of the rolls will once again be on trial.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

N.K. Bhoopesh is Assistant Editor, Outlook. He is based out of Kochi, Kerala

Democracy is about ballots, but also about memory—who safeguards both, and who seeks to rewrite them? Outlook’s September 11, 2025 issue, 'Election Omission' probes these erasures—of voters, voices, and histories—asking what they mean for India’s democratic future. This article appeared in print as 'Mahadevapura: Where Strangers Came To The Rolls'