The entry of foreign universities into India under NEP 2020 and UGC’s 2023 regulations offers promise of “world-class” education but risks deepening structural divides.

Without safeguards, foreign campuses may accelerate commodification, reinforce Western dominance in curricula, and undermine the NEP’s vision of education as a public good.

In a government school nestled among the pine-clad hills of Kashmir, our primary school classroom was in open air, only a tarpaulin sheet served as a roof, and the cold ground acted as our desks. With only two of teachers for five classes, the educational framework was sustained not through physical structures, but through unwavering determination.

Years later, we found ourselves at Jamia Millia Islamia and the University of Kashmir, navigating the journey of higher education with the support of public subsidies, scholarships, and unwavering determination. Today, we teach students at a university in Punjab, nurturing those from similar backgrounds while observing intently as India embarks on an exciting new chapter: welcoming foreign universities into its fold.

India’s higher education landscape is undergoing a seismic shift. Flush with the ambition of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and propelled by the University Grants Commission’s (UGC) 2023 regulations, foreign universities are finally setting foot on Indian soil. Five prestigious institutions, including the University of Liverpool (UK), Victoria University (Australia), and Illinois Institute of Technology (USA) hold Letters of Intent in this connection. These are supposed to join pioneers like Deakin University and the University of Wollongong already operating in Gujarat’s gleaming GIFT City, and the University of Southampton in Gurugram’s corporate hub. This transition is seen as a crucial element of India’s rise on the global stage facilitating access to “world-class” education while eliminating the necessity to leave the country.

This development appears to hold great potential. As participants in India’s delicate yet essential public education framework, we ponder: Will foreign campuses act as pathways to opportunity or merely stand as symbols of privilege?

The NEP 2020 is a rich fabric interlaced with admirable elements: a 50% Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER), the promotion of Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), efforts to stem brain drain, and the assertion that education is a public good rather than a mere commodity. The arrival of international universities weaves a daring thread into this tapestry, a means to retain talent domestically, adopt “world-class” teaching methods, and enhance India’s position on the global stage. This holds promise. Imagine educational breakthroughs igniting transformations throughout the entire system. These are significant positives.

Let us examine the financial aspects of international university campuses. In their home countries, institutions such as Deakin impose tuition fees that can exceed ₹15–20 lakhs annually for undergraduate programs. Although Indian campuses are anticipated to provide more affordable options, initial projections indicate that they might still impose fees ranging from ₹8–12 lakhs per year, far exceeding what most middle and lower income families can afford. At the same time, over 60% of students in India pursue their education in state public universities and colleges, where yearly tuition fees seldom exceed ₹10,000.

Rather than closing divides, foreign campuses may inadvertently reinforce a dual system: one for urban elites enjoying climate-controlled environments and prestigious curricula, and another for the large majority facing challenges in under resourced state institutions. Are we bracing for a more stark structural and curricular divide in India?

According to the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023, these foreign campuses enjoy exemptions from numerous regulatory limitations that Indian universities encounter.

They have the freedom to establish their own fee structures, bring in international faculty, and independently shape their curricula. In stark contrast, Indian public universities find themselves caught in a complex maze of approvals from the UGC, AICTE, state governments, and various affiliating bodies. In numerous states, the hiring of university faculty has been on hold for years. Institutions face significant challenges with vacancy rates reaching as high as 40–50 per cent, especially in underdeveloped areas, according to a report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education in 2021. How can one explain this predicament of ‘autonomous foreign’ and the bureaucratically ‘constrained indigenous’?

Then, what about India’s indigenous traditions and knowledge systems so much stressed in the NEP 20? Are these only for the same tarpaulin furnished schools and India’s public institutions, in which the under and unprivileged continue to have the primary stake? Are we, therefore, reworking and entrenching more the divides that continue to mark India’s post-colonial social formation?

Although the NEP 20 asserts that education is a public good, the introduction of foreign campuses shifts the system towards commodification. In contrast to Indian public universities, which cannot keep surpluses and are required to reinvest their earnings, foreign campuses will have the opportunity to send profits back to their home countries. The message resonates strongly: for Indians, education represents a noble mission; for those from outside, it’s merely a marketplace.

This imbalance not only undermines the assumed essence of the NEP but may also undermine local institutions. It seems improbable that public universities, which are already functioning with limited financial resources (as government spending on education remains stagnant at approximately 2.9 per cent of GDP, significantly lower than the NEP’s goal of 6%), will obtain the necessary backing to keep pace.

As noted earlier, given their autonomy, it seems that these institutions show minimal interest or capability in incorporating Indian languages, indigenous knowledge, or local histories into their curriculum. What we might observe is a strengthening of Western intellectual frameworks quietly overshadowing Indian viewpoints under the guise of “global relevance.” This apprehension is not unfounded; it is a truth revealed by the annals of history.

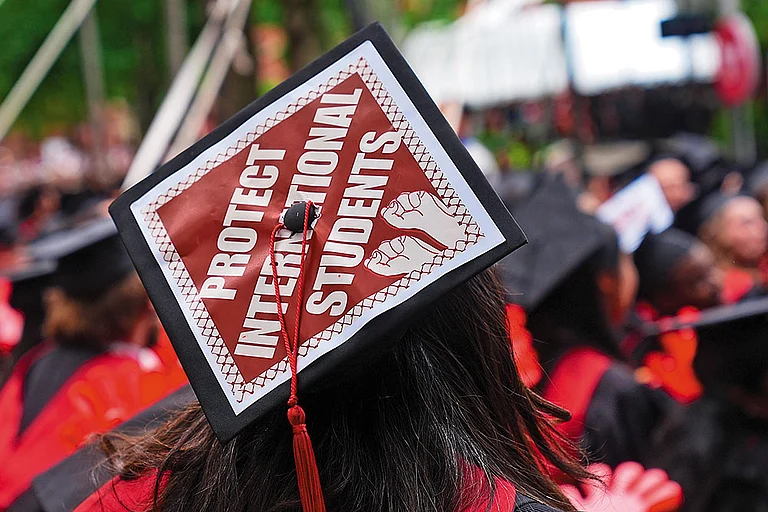

In 2024, a remarkable 1.3 million students from India ventured abroad for higher education, as reported by the Ministry of External Affairs. The notion that foreign campuses in India will decrease this figure is rather hopeful. It is more probable that a “feeder model” will emerge, allowing students to utilise the Indian campus of a foreign university as a launchpad for obtaining postgraduate admissions or lateral transfers overseas.

The new campuses might not effectively address the brain drain but simply redirect its course. They will cater to individuals who already possess the means for global mobility not to those who have been historically marginalised from it.

What can be done?

This piece is not intended to decry the coming of foreign universities to India. When conducted fairly in view of India’s social make-up, international academic exchange has the potential to elevate many. This necessitates a profound reconsideration of the integration of these institutions:

It is essential for foreign campuses to ensure that a minimum of 25 per cent of seats are designated for students from underprivileged backgrounds, with the provision of full or partial scholarships to support them.

Create incentives, like land grants and infrastructure assistance for international universities to set up campuses in underdeveloped districts or areas with low Gross Enrolment Ratios, rather than restricting them to particular urban centres. Joint degree programs, faculty exchanges, and collaborative research with state and central universities should be essential and not merely optional.

International institutions should be required to release yearly information regarding admissions, socio-economic demographics, scholarship allocation, and research influence in India.

The aspiration to transform India into a global education centre is certainly well-founded. But a centre for whom? For the students in Gurugram enjoying global exposure and the privileges of wealth and class or for a less heard of student in rural India, who studies underneath a corrugated tin roof and aspires to earn a college degree?

Our personal experiences from attending public schools in the backyards of display-able urban India to pursuing higher education at public universities in Delhi and Srinagar demonstrate that accessible quality education has the power to change lives. The implementation of the foreign university model today threatens to undermine the foundational structures that might enable these transformations to occur. Can we imagine a framework that can be enabling for the underprivileged? This is a question for wider public debate to evolve a democratic consensus on issues that matter to many Indians and many India’s. If India is to construct glass towers, they should be anchored with foundations robust enough to coexist with the tarpaulin classrooms.

This invites a serious rethinking of the much hailed educational reform. The matter at hand is the type of social order we aspire to construct. The NEP should uphold not only global aspirations but also local, unattended citizens by adhering to constitutional principles of equality, access, and justice.

(Dr Zahoor Ahmad Mir, Dr Waseem Ahmad Bhat and Dr Irfan Ahmad Bhat. All authors are Assistant Professor at Akal University, Bhatinda Punjab. Dr Mir holds PhD from Jamia Millia Islamia, Dr Bhat and Bhat have done their PhD from Kashmir University.)