Summary of this article

Despite the 1976 law and rehabilitation schemes, millions remain trapped in debt bondage, with poor enforcement and denied entitlements keeping the system alive.

The 1976 Bonded Labour Act is poorly enforced, with district and state authorities routinely ignoring it, as per the 2025 NCCEBL report on 950 release certificate holders.

The 2016 Central Rehabilitation Scheme fails due to weak implementation, poor coordination, and denial of benefits, forcing rescued workers back into exploitative unorganised jobs.

The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 has once again become the talk of the town for today because this year it completes 50 years since its introduction into the Indian constitution. Some people are hailing it as a moral milestone that independent India achieved, but has this half century actually made a difference?

The National Campaign Committee for Eradication of Bonded Labour (NCCEBL), a coalition of activists, NGOs, and trade unions, in a report released in November 2025, has cited widespread failure to enforce the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976.

The report, based on surveys of 950 bonded labourers who had been issued official Release Certificates, finds that the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act is consistently ignored by district and state authorities throughout the country.

The report also highlights that the Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers (2016) remains largely ineffective on the ground. It is suffering from poor implementation, lack of coordination between agencies, and the routine denial of entitled benefits.

As a result, many rescued bonded labourers find themselves trapped in an endless nightmare, as employment opportunities dry up, and their rightful access to livelihood schemes such as MGNREGA is repeatedly ignored or undermined, they have no option but to look for work in unorganised sectors which exploit them.

The report finds that bonded labour continues in both traditional and evolving forms across India’s agricultural and industrial sectors. Examples include the Harwai system in Madhya Pradesh, where landless labourers are compelled to repay informal loans through indefinite farm work, and the Chakar Pratha system in Gujarat, under which debt is passed down through generations, binding families to the same creditors.

In Odisha, barbers from marginalised castes remain obliged to provide unpaid services to dominant-caste households. In Maharashtra, whole families are trapped in long-term contracts within the sugarcane sector, with little scope for escape or fair wages.

These practices illustrate how bonded labour persists despite legal prohibitions, affecting workers in different regions and occupations.

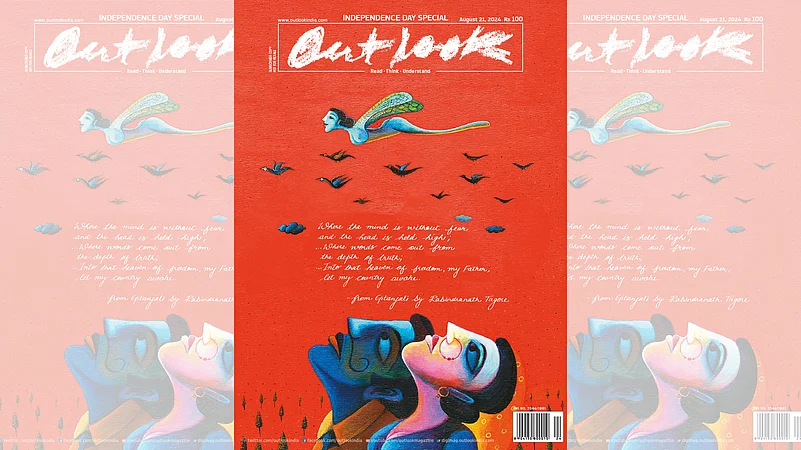

Outlook Magazine in its 2024 Independence Day issue went to the ground to scratch the very surface of a social evil that has wreaked havoc in the lives of millions whose hands and feet wake up before their mind as the first light of dawn strikes, who work 16-18 hours in extremely poor conditions, just to have a sense of freedom while sacrificing their lives to bonded labour.

The story, titled "Dreamers Of Equality", points out that while the country gained freedom as a nation, political and personal freedoms remain elusive for large numbers due to caste, economic hardship, and social barriers.

The issue documents various forms of ongoing bondage and inequality. Bonded labour persists in defiance of the 1976 abolition law, leaving workers still searching for real independence. Modern unfreedoms in the labour market are highlighted, with calls to reduce inequalities in order to protect the republic, whereas rehabilitation efforts for survivors of trafficking and bonded labour often fall short, increasing the risk of re-victimisation.

Caste discrimination receives close attention. Untouchability continues to affect Dalits despite legal measures, with artisans in parts of Himachal Pradesh facing caste-based restrictions in their work and de-notified tribes carrying the burden of colonial-era criminal labels that linger in independent India. Inter-caste marriages are presented as one means to challenge the caste system. In the magazine hunger in isolated regions and migration driven by economic gaps in places like Jharkhand has also been covered underscoring regional and class divides.

Other reports cover challenges for marginalised groups, and call for efforts to educate children from the Phanse Pardi tribe through a dedicated school are described amid funding and survival issues.

Issues of expression and rights include censorship faced by artists linked to groups under state pressure. The distinction is drawn between freedom from restrictions and the positive freedom to act without interference. Threats to constitutional freedoms are noted, along with questions about whether nationalist narratives include subaltern perspectives. Political prisoners receive limited freedoms, with accounts of maintaining mental resilience in confinement.

Cultural and environmental topics appear as well. Dying languages, particularly those of marginalised tribes, are at risk of extinction. Religion is critiqued as a means of control over weaker sections in tribal areas. Pollution, unplanned development in the Himalayas, and the commodification of cinema are discussed as barriers to broader freedoms. Lynching incidents, the push for period leave as a marker of independence, and the role of opposition in democracy add to the mix. A satirical piece offers a humorous take on inequality.

Taken together, the articles use the Independence Day frame to catalogue persistent unfreedoms across economic exploitation, caste hierarchies, minority rights, censorship, and ecological threats.

The issue stresses that true freedom remains out of reach for many, despite national progress.