Tule Ram stands with folded hands and bowed head at a distance from the procession as the devrath—palanquin of the goddess, borne on the shoulders of young devotees—sways in harmony to the rhythm of traditional instruments played by a band of local Dalit artistes known by the name of their caste, Bajantri.

Nobody watching the procession could miss the palanquin’s most eye-catching feature: the mohras or visages of Mata Ambika Adi Shakti—feminine aspect of Shivashakti, the primal force that spontaneously gave rise to all creation according to Hindu mythology—handcrafted from metal by Tule Ram. The 39-year-old, however, is not allowed to touch the sacred creations of his artistic labour—the skilfully shaped forms depicting the revered deity of Banwas village in the Thachi valley of Seraj region in Himachal’s Mandi district.

Belonging to the fourth generation of a local family of traditional metalwork artisans, Tule Ram’s birth in the Lohar or blacksmith’s caste—a Scheduled Caste in most of Himachal Pradesh except a few districts like Kangra where they are listed among the Other Backward Classes (OBCs)—is sufficient to deem his touch ‘impure’ by the caste norms of purity-pollution that have traditionally determined who touches what and interacts with whom, and how.

Even though Article 17 of the Constitution of India, enacted three years after Independence, explicitly forbids the enforcement of any disability arising out of the age-old practice of untouchability, it often happens behind the veil of ancient customs and religious practices. This is why, while he accompanies the procession up to the kothi, the goddess’s temple in his village, the artisan ensures there is always a gap between him and the palanquin made beautiful by the visages he had crafted.

In fact, once the priest performs the consecration ritual called prana-pratistha, figuratively breathing divine life into the visages that the artisan had meticulously crafted from eight metals, including gold and silver, it is not just the mohras, now said to be imbued with the spirit of the deity, that become ‘untouchable’ for the artisan.

The entire sacred space—the temple or the palanquin that the visages adorn—turns into a no-go zone for him. Free access to such spaces is permitted only to those placed higher in the hierarchy of caste. “After the mohras are ready, we perform some rituals associated with Guru Vishwakarma (the Hindu god of craftsmanship) to ensure purity and the fulfilment of our sacred duty,” Tule Ram says. “Once the consecration ceremony is done, however, we forfeit the right to approach and touch the mohras, which are either displayed in the temples or mounted on the palanquin.”

One of the oldest deities of the Seraj region and said to have been worshipped for centuries, Mata Ambika is also carried on a palanquin to the international Shivaratri festival held annually in Mandi town. The processions of numerous other deities on their palanquins also arrive in the town during this festival. Mandi and Kullu districts are home to more than 500 deities each.

Tule Ram had teamed up with a fellow artisan, Dev, to sculpt all the eight visages of Mata Ambika Adi Shakti. It took them four months. According to Tej Ram, the ‘gur’ or oracle of the deity, more than 1 kg of 24-carat gold and 10 kg silver along with other metals were used to make the visages.

The work of the artisans involves handcrafting the metal into the finest shapes as visages, idols, palanquins and other sacred artefacts. The main idol called the Molee Mohra is made using a process called lost-wax casting in which fire, water and soil (from crushed bricks) are used to create intricate moulds for pouring in the molten ‘asthadhatu’, an alloy of eight metals—gold, silver, brass, iron, tin, mercury, copper and zinc. An alternative process involves the embossing of metal sheets to create images in a completely handcrafted manner.

The artisans’ workday is rigorous and ritualistic. They are allowed to eat only once, and strictly nothing non-vegetarian, in order to maintain their ritual purity and as a test of their devotion. In the worldview of caste hierarchy, every substance, including food, is imbued with a predetermined degree of purity, which also determines the ‘purity’ of the person who comes in contact with it.

As contact with other persons also similarly affects this measure of purity, the artisans are required to stay away from their families and kin even though the work takes months, sometimes even longer than a year, to finish. They have to stay within a designated space, bathe early in the morning before starting the day’s work, wear clothes that are washed daily, walk barefoot and keep away from all intoxicants.

While working, some artisans love to listen to soft devotional music and chants, hoping to channel some divine energy into the artefacts they create. Once the artefacts are completed, they are handed over to the temple’s management committee for consecration ceremonies.

Located just 200 metres from the Thachi bus stand, the Dev Bitthu Narayan temple, one of the oldest and also known as the Lakshmi Narayan temple, is out of bounds, like many other temples, to people from the marginalised castes. “The restriction is based on the social order that everyone accepts, including the local artisan community,” says the octogenarian head priest, Pandit Ott Ram Sharma. “This area, especially Thachi, is blessed. It is here that the tales of ancient deities are interwoven with the unique craftsmanship of metalwork, stone carving, woodwork and so on, combining art seamlessly with spirituality.” Sharma has only words of praise for the craftmanship of the mohra-making artisans who cannot enter the temple yet keep alive a centuries-old heritage. The craft could be slowly dying, however, as the younger generations lack the motivation to learn and practise it.

Mandi-based photographer Birbal Sharma, who has also set up a local gallery showcasing Himachal’s “dev sanskriti” (deity culture), ancient religious architecture, handicrafts and more, points out that the craft is not economically rewarding despite the long hours and rigorous rituals. “There is also caste-based discrimination that thrives on faith, a sphere that certainly needs social interventions,” he says.

Former chief minister Jairam Thakur admits that such caste-based exclusion exists but calls it a “remnant of a long-abandoned caste system”. The six-time MLA representing Seraj finds it “unfortunate” that the prevailing practices make sacred spaces out of bounds for the very metalcraft artisans who contribute to making those places sacred in the first place. “This persists despite the immense religious contributions made through the making of mohras that is the artisans’ family tradition. Some reforms are surely needed,” he says.

That caste does make a big difference is evident from the example of Veer Singh, a metalwork artisan immersed in his craft in a small room adjacent to the temple of the village deity at Kathgiri, 11 km from Mandi town. This room will be his world for another two months. “Forty years ago or so,” says the 34-year-old, “my father Gimber Singh, also a master artisan from Thachi, had made visages and other metal artefacts for this deity. I am lucky that the deity has chosen me to carry on my father’s legacy.” As this temple belongs to a local Dalit family, nobody stops Singh from entering the premises and touching the idols or mohras. “This would be impossible in a temple of the higher castes,” he says.

Singh’s day begins with a few morning rituals before he starts working at 8 am with the two others in his team—his younger brother and a trainee artisan. “I strictly observe the rules on diet to uphold the sanctity of the work. I typically have a banana and a glass of milk for a light breakfast, and conclude my day with my main meal at 8 pm,” he says.

Caste discrimination is discouraging young artists from taking up their traditional vocation.

Having attained some recognition for his metal craftsmanship, Singh often travels to participate in art and craft exhibitions within and outside Himachal for marketing his creations. He has also been empanelled by HIMCRAFT, the Himachal Pradesh Handicraft and Handloom Corporation, which will buy his products like palanquins, visages, sacred art pieces and musical instruments for gifting to VIPs.

Indeed, such state patronage has proved a godsent for other artisans too. A 35-kg seven-feet metal trishul (the trident of Lord Shiva) crafted by Thachi artisan Hukam Ram was presented to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Mandi on December 27, 2021. The following year, a Narsingha (an S-shaped trumpet) made by three artisans—Khube Ram, Lotum Ram and Reet Ram of Chaodi village—was gifted to the PM. “They took 18 days to make the 46-inch traditional wind instrument, weighing four kg,” says Ved Ram, a metal artisan who also doubles as a social activist. “We are suspended neither in the sky nor on the ground,” he says.

Admitting that the artisans do face social challenges, Himachal Pradesh Sarva Devata Samiti’s president Shivpal expresses admiration for their role in preserving ancient traditions and showcasing them to the world. “The best thing about our craftsmen is their unwavering faith in the ‘dev sanskriti’,” he says. “Equally important is the role of Bajantris, the Dalit musicians. We are doing our best to support them financially to prevent their economic and social estrangement. This cannot be achieved overnight.” Calling the making of mohras, devrath and ceremonial musical instruments a “sacred duty” of the artisans, mostly Lohar and Barai (carpenters), Shivpal adds, “They are aware of their boundaries and strive to uphold the centuries-old heritage, despite feeling excluded.”

Extolling the artisans’ role in upholding a culture that also enforces their exclusion from sacred spaces, however, does little to hide the simmering discontent that reveals itself in the feelings of those who are excluded and discriminated against. Many admit that the sheer pressure to survive—in both the economic and the social sense—leaves them with little choice but to follow the enforced norms just like their ancestors did.

“The system surrounding the deities is extremely rigid and resistant to change,” says a Dalit scholar from Mandi who didn’t wish to be named. “Rebellion could lead to a loss of future opportunities in metal and woodcraft, and, many fear, might even provoke a deity’s curse. Hence, they find it advisable to adhere to the established customs and maintain the faith. Seeking legal redress is really out of the question here.”

Shimla-based Dalit author S R Harnot blames the failure of strict laws against caste discrimination to end the suffering of the oppressed castes on a lack of adequate social awareness. Recalling how a few years ago he had to file an FIR to challenge a temple’s notice barring entry to people from the “lower” castes, Harnot points out that such discriminatory practices are indeed quite prevalent within the framework of deity culture.

“Caste discrimination is a factor that drives away the educated young people of the artisans’ families from their traditional vocation,” says Megh Singh, a well-known artisan in Thachi whose finest works, mainly devraths, are found in hundreds of temples across the state. He takes pride in his two sons who have been trained in the craft. “They will carry forward my rich legacy. And one day I hope the adverse social factors, too, will fade way,” he says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

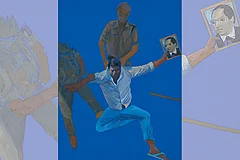

These very “social factors” have drawn the attention of a young writer and filmmaker Devkanya Thakur. “In Kullu, there are families, some in their third or fourth generations, traditionally engaged in the craftsmanship of making mohras for deities and temples. It’s sad how they face segregation once the mohras are enshrined,” says Thakur, whose 80-minute feature film, Mohra, revolves around a mohra craftsman Nirtu and his six-year-old son, Guddu. Nirtu, a Dalit, faces casteist wrath after Guddu playfully enters a temple where consecration rituals are being performed. Shot in Kullu with locals playing all the protagonists and speaking the local Kullvi dialect, the film gives voice to those whose inability to pose an organised challenge to the social deprivation of their community that is otherwise integral to the region’s deity culture is often misread as acquiescence.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Impure Hand')