Trigger Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide. Reader discretion is advised. If you or someone you know is struggling, please contact these numbers.

Helpline: iCall (9152987821) or AASRA (+91-22-27546669) — Available 24/7.

The author was on an overnight train from Howrah to Koraput.

They found a diary that belonged to someone named Brinni.

Fragmented entries revealed it was a social scientist's research project.

If, in an instant, we were to face the reality of death today, what memories would rise unbidden to the surface of our mind? Which moments—those fleeting, profound fragments of our existence—would linger and haunt us in our final breaths? What cherished joys or unresolved regrets would echo within us, knowing they are about to dissolve into the void, lost forever with our passing?

A few summers ago, I was on an overnight train from Howrah to Koraput. As the train pulled into its final stop the next morning and I prepared to disembark, I noticed something unusual—a weathered, anonymous diary lying forgotten beneath the seat, tucked into a corner where luggage is usually stowed. No one was around to claim it, and perhaps it had been there for sometime, unnoticed by others. As I began turning the pages, I noticed that the diary belonged to someone named Brinni. It struck me then—perhaps she was the quiet woman from the upper berth, the one I had exchanged a few words with the night before. I gently placed the diary in my bag and stepped off the train. Later, I checked the list of passengers pasted on the compartment wall, but there was no one named Brinni.

A few days later, as I started going through the pages, I found fragmented entries—confessions, suicide notes, court verdicts, intimate reflections, and vivid descriptions of spaces. I soon realised the diary was part of a detailed research project by a social scientist—an exploration of thanatology. Alongside the testimonies, typewritten notes, newspaper cuttings were pasted throughout the pages, recounting someone’s travels across several countries to collect stories—not of death itself, but of the memories people hold onto in their final moments. These weren’t just about terminal illness or the trauma of violent loss, but also accounts of suicide, and the emotional traces left behind by the inevitability of death.

Slowly I became fascinated by these notes—so much so that I began retracing the journey outlined in the diary. I visited the places it mentioned: Motels, college hostels, abandoned hospitals, railway stations. In time, the diary became a guide, leading me through landscapes heavy with memory, each site emerged as a symbol of collective remembrance. It unearthed striking stories woven through layers of social, political, and moral inequality. In a country like India, where discrimination based on caste, class, gender, and religion persists—and where suicide rates have sharply risen since 2015—mental health remains widely stigmatised. Stories shaped by gender-based violence, domestic abuse, dowry-related pressure, and rape often go undocumented and find no space in mainstream media.

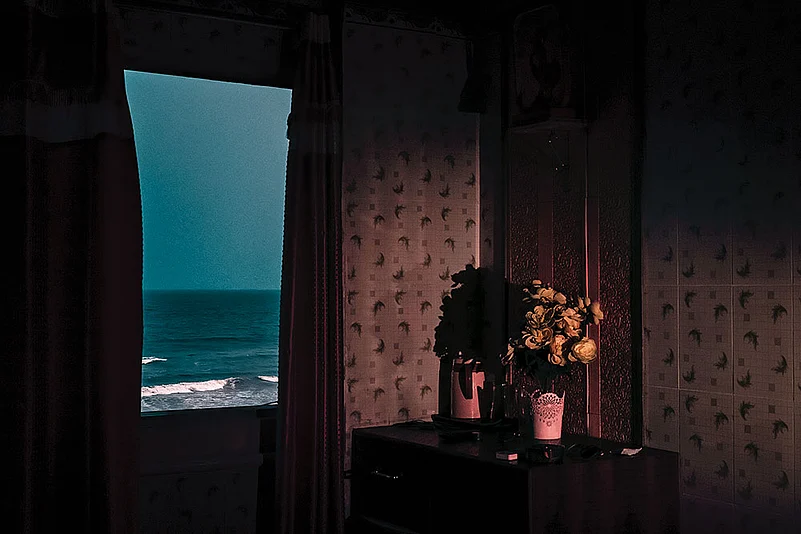

From the diary, I’m developing several individual stories—each transformed into a visual narrative using photographs and fragments of hand written text.

These are not direct reenactments, but political interpretations of memory, absence, and survival. My aim is to create a shared space for reflection—where personal grief connects to collective history.

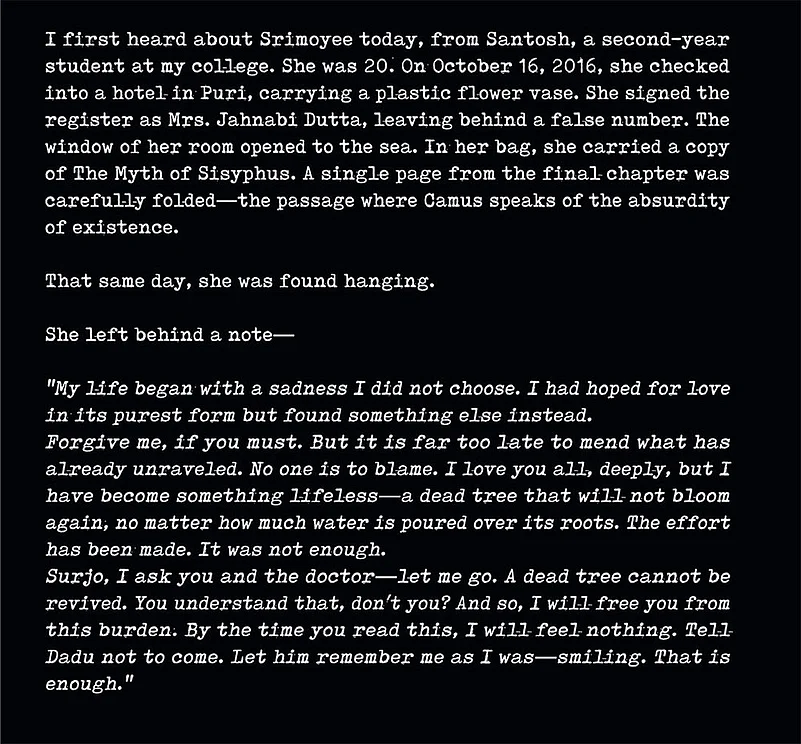

One among the case studies in the diary is Srimoyee—a woman who died in a hotel room in Puri, India. On October 16, 2016, she checked into Hotel Sea View, carrying a plastic flower vase and a copy of The Myth of Sisyphus. A single page from the final chapter was carefully folded—the passage where Camus reflects on the absurdity of existence. That same day, she was found hanging.

Srimoyee’s story is not just hers—it echoes a larger, unspoken reality. Since she was a girl child, she was subject to constant discrimination within her own family and even by her own parents. This is still a grave reality in our society, where the birth of a girl child is still considered as a liability and is treated unfairly and a male child is given the preference. In a world where so many stories slip through unnoticed, hers lingers—a quiet question about memory, loss, and the invisible weight so many carry.

‘We Need to Talk in Whispers’ delves into the emotional turbulence of such moments, exploring the delicate space between desire and dread, dream and reality. At its core lies a deep engagement with the complexities of mental health, vulnerability, and the human psyche when confronted with the certainty of death. Through this process, I hope to foster empathy, to deepen our collective understanding of mental health, and to create a space for reflection—on our own lives, our hidden griefs, and the quiet strength we summon in the face of life’s inevitable end.

Text & Photographs: Soumya Sankar Bose

From the diary, I’m developing several individual stories—each transformed into a visual narrative using photographs and fragments of hand written text.

These are not direct reenactments, but political interpretations of memory, absence, and survival. My aim is to create a shared space for reflection—where personal grief connects to collective history.

In its August 21 issue, Outlook collaborated with The Banyan India to take a hard look at the community and care provided to those with mental health disorders in India. From the inmates in mental health facilities across India—Ranchi to Lucknow—to the mental health impact of conflict journalism, to the chronic stress caused by the caste system, our reporters and columnists shed light on and questioned the stigma weighing down the vulnerable communities where mental health disorders are prevalent. This copy appeared in print as We Need To Talk In Whispers.