By June 2020, around 32 lakh migrant workers had returned to Bihar. But the Inter-State Migrant Workers Act of 1979 was barely enforced.

Sanjay Sahni, one of the migrant workers, even filed his nomination as an independent candidate in Kurhani in 2020.

The migrant labourers are back to the cities doing their daily drudgery after the recently concluded elections.

In 2020, I chased after a bus full of migrant labourers headed to New Delhi Railway Station to board the Shramik train to Bihar. They looked forward to nothing in particular. They barely glanced out of the bus windows. The city was now a hostile, emptied-out place where they had queued up for food. The betrayal came from everywhere. The pandemic laid bare the failures of society and of governments at both the Centre and the states, none equipped to care for the poor migrants, who were clueless about survival. The future looked particularly bleak for them.

That was on May 9, 2020. Bihar was the first state to conduct elections that year. Many migrant workers had already started the long journey home on foot in the harsh summer, carrying their meagre belongings and many died. The Bihar government was opposed to their return, citing lack of resources. On May 9, as the first Shramik train left Delhi, I called out, waved and got nothing back. Desperate for their stories, I tossed my number, hastily scribbled on torn notebook pages, at the windows and waited. A couple of them called, with narratives of hunger, thirst, quarantine dread and the blunt collision of state apathy and migrant despair.

On May 20, I met Balram and Shyam at the Delhi-Noida border, hauling a rickety Rs 500 bicycle for the long ride to Samastipur. Shyam had driven an e-rickshaw. Balram had taken a Rs 30,000 loan for his, only for the lockdown to gut his future. No trains, no buses, no ration. They waited in the dark until they boarded a bus to Muzaffarpur. What cut deepest was the loss of dignity, becoming supplicants before an indifferent system.

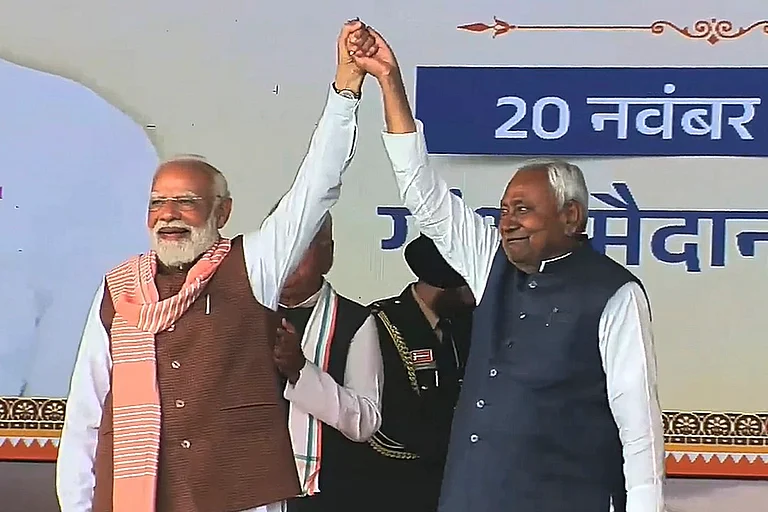

In that election, the Opposition promised 10 lakh jobs. Tejashwi Yadav hit CM Nitish Kumar for failing to create work, saying four million migrants had returned in the lockdown. Soon they left again. They had to. Bihar’s ‘development’ never held space for them.

By June 2020, around 32 lakh migrant workers had returned to Bihar. But the Inter-State Migrant Workers Act of 1979 was barely enforced, and Census or National Sample Survey counts habitually missed seasonal migrants, shutting many out of Below Poverty Line surveys.

Bihar has the highest proportion of outward migration of workers in India. In 2020, the Election Commission of India had enrolled 6.5 lakh new voters and the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in 2020 announced the Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan—an ambitious campaign for providing work to the migrant workers and poor sections affected by Covid-19 induced lockdown.

But it wasn’t enough.

I was in Bihar then. In Darbhanga, I met many migrant workers who had no idea what they would do.

Jitender Kumar Prasad, 26, who worked in Gurugram in an export house, migrated when he was 16 years old. He said that in his village, there were only old people. “Everyone in this village goes away. Even women,” he said. “We returned somehow after our money was over. They want our votes, but are they concerned whether we live or die?”

In Muzaffarpur, Sushil Rai, 36, said the lockdown broke him. He, along with his son and a friend, left Hyderabad, walking home until a bus came along. “Our own government abandoned us. We cry, we don’t sleep. We won’t stay for the elections. We are just ghosts here,” he had told me.

The Nitish Kumar government had then announced a deposit of Rs 1,000 for every labourer.

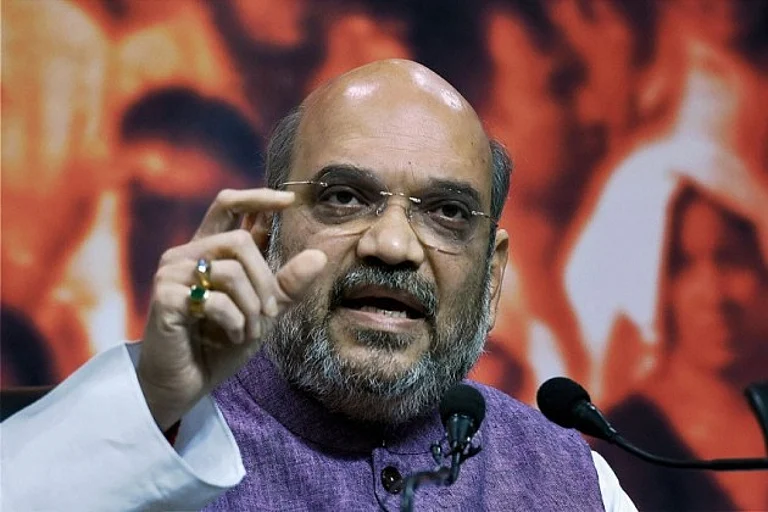

But there was no outrage despite the Bihar government first denying entry to the returning migrant workers. The Bharatiya Janata Party and the Janata Dal (United) were partners in a ruling alliance then. The government had given migrant workers Rs 500 for three months, but that wasn’t enough, many migrants told me.

Yet, they weren’t angry. They were just sad.

Sanjay Sahni, one of the migrant workers, even filed his nomination as an independent candidate in Kurhani in 2020. Sahni said he would go for issue-based politics as opposed to caste-based politics. He was pitched against the BJP’s Kedar Prasad Gupta. He lost.

I had hoped that this was the election where the labourer political identity would emerge in Bihar.

But hope is a luxury in Bihar.

The migrant labourers are back to the cities doing their daily drudgery after the recently concluded elections. They had told me then they would vote for the NDA. When I had asked why, they said they thought it wasn’t their fault that they were poor and that they were abandoned.

A new government will be formed yet again. Sahni didn’t fight the election this time. He perhaps realised that hope is our biggest enemy.

As for me, the old notebooks remain as reminders of betrayal and abandonment.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Chinki Sinha is Editor, Outlook Magazine

This article appeared as 'Broken in Bihar' in Outlook’s December 1, 2025 issue as 'The Burden of Bihar' which explores how the latest election results tell their own story of continuity and aspiration, and the new government inherits a mandate weighted with expectations. The issue reveals how politics, people, and power intersect in ways that shape who we are—and where we go next.