Educate Girls, which won the 2025 Ramon Magsaysay Prize under the leadership of Safeena Hussain, has transformed access to education in rural India by mobilising Team Balika—local youth who are often the most educated in their villages—to bring girls back to classrooms

Through programmes like Vidya (for under-15 girls) and Pragati (for older adolescents), the organisation tackles barriers such as child marriage, lack of sanitation, safety concerns, and social hierarchies, combining door-to-door outreach with community mobilisation.

Since 2007, Educate Girls has expanded to over 30,000 villages, re-enrolled two million girls, reached 2.4 million learners through remedial education, and now aims to impact 10 million learners by 2035, proving that community-led change can break cycles of exclusion.

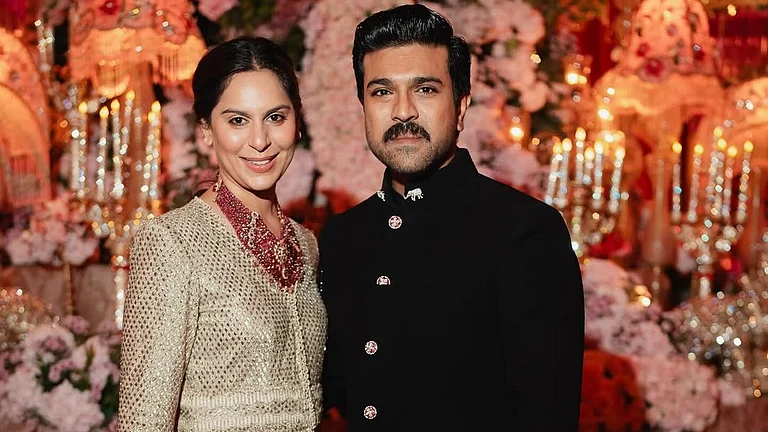

In five per cent of the villages in India, forty per cent of girls in the school-going age are out of school. This was not just a statistic, it was a reality written into the lives of children who rose before dawn to fetch water, carried younger siblings on their hips, and watched their brothers go off to school while they had to stay back at home. This figure generated from predictive algorithm model developed by Educate Girls, became a turning point in 2018-19 for Educate Girls, the non-profit organisation founded by Safeena Husain, which has been awarded the 2025 Ramon Magsaysay Prize.

The story began in 2007 in the dry, sunburnt landscape of Pali district, Rajasthan. In those villages with mud walls and narrow lanes, the Educate Girls team observed a pattern that was difficult to ignore. Girls were technically “enrolled” in schools, their names written in registers, yet their classrooms sat half-empty. The reasons for their absence lay in kitchens and courtyards: daughters being asked to grind grain, tend to goats, care for toddlers, or help their mothers in the fields. Even in the places where government programmes like the mid-day meal scheme had succeeded in tackling hunger, the deeper obstacles remained—the social hierarchies that placed a boy’s schooling above a girl’s and the worry that a daughter with too much education would make her an “unsuitable” candidate for marriage.

At first, Educate Girls team tried to go door to door, speaking directly with families. But outsiders were met with cautious smiles and polite evasions. Strangers could not persuade them to educate their girls. What was needed was a voice from within. From this realisation was born Team Balika—a network of local volunteers, often the most educated in their villages, who carried the authority of familiarity. Their task was simple in writing but arduous in practice: to identify out-of-school girls, convince their families, walk them to class, and return again and again to make sure they stayed in school.

Savita (name changed), 21 from Girvar village in Rajasthan’s Sirohi district, remembers the resistance she encountered. Her hamlet was located among rocky hills. The nearest school was 3 to 4 kilometres away. “Schools are too far away from the hamlets,” she says. “Parents think, what if our girl gets influenced by outsiders' thoughts and marries outside the community? What if they study and step out? Standing against your own family is looked down upon.” For her, convincing families meant finding practical entry points. “There are no jobs here," she says. "Mostly, I tell them, you can enroll them in anganwadis as teachers, because teaching is one thing they can do after Class 10. Marriage is the final destination, so sometimes I have to show them that education itself can lead there in a respectable way.” She remembers working with field coordinator Bagha Ramji, who would visit tribal hamlets where girls themselves resisted schooling because they had grown up believing it was unnecessary. Muskan, another volunteer, adds that “the camps are sometimes set up in the panchayat room,” spilling over with girls who never imagined they’d sit behind a desk again.

Across the states of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar, this model began to grow. In one village after another, Vidya, a programme targeting girls under 15, wove itself into the rhythm of everyday life. Volunteers went from home to home collecting documents that families often did not have—birth certificates, caste papers, proof of residence. They sat with sarpanches under banyan trees, gathered parents in mohalla meetings, and invoked the voices of teachers, priests, and elders to slowly tilt the balance toward acceptance. These meetings were filled with a chorus of doubts, hesitations and reassurances—until finally, a nod from the father or a word from the grandmother would open up the path back to school.

The scale of the problem had been made clear by reports such as the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2023, which found that while 95 per cent of children in rural India were enrolled in schools, dropout rates among girls spiked alarmingly after Class 5. The reasons were many: the school building without a toilet, the unpaved road that turned treacherous in the monsoon, the absence of boundary walls that made parents worry about safety. For adolescent girls, menstruation without sanitation facilities meant missed classes, which soon turned into permanent withdrawal. In many households, the pressures of poverty dictated choices—books for sons, chores for daughters. And beneath it all lay the weight of social expectations: a girl’s education was seen not as an investment, but as a possible threat to marriage negotiations.

For Safeena Husain, the founder of Educate Girls, these patterns were painfully familiar. Her own childhood had been punctuated by a three-year break from school before she went to the London School of Economics, the result of family circumstances marked by poverty and neglect. That left an indelible mark, teaching her what exclusion feels like. "My aunt adopted me and helped me navigate from there. The idea of Balika Volunteer has originated from there only." Later, during the three years she spent working on health projects in Ecuador and the Amazon, she began to see another dimension of change. “While working in the Amazon, I realised that true change comes from within communities themselves,” she says. “Leadership cannot be imposed—it grows when people are equipped with the tools and thoughts of empowerment, and then they create their own methods of development.” This conviction that development must be locally owned became the architecture of Educate Girls.

The Team Balika volunteers became advocates, bureaucratic-hurdle navigators, and sometimes the only consistent allies in a girl’s fight to stay in school. When schools lacked toilets, they petitioned authorities. When teachers neglected attendance, they intervened. Over time, more than 650 of these volunteers joined Educate Girls in formal roles, proof that community leadership could grow into institutional strength.

In Uttar Pradesh, the barriers were less about geography and more about community identity. In districts like Fatehpur, with a large Muslim population, families often turned to madrasas. Some government-recognised institutions included Hindi, English, and Mathematics, but many unrecognised ones focused exclusively on religious instruction. Here, persuasion meant walking a tightrope. “We cannot go against a community,” explains Alok Singh (name changed), Educate Girls’ state program manager. “When we talk about madrasas, we also talk about the community. We encourage families to balance religious learning with some form of formal education.”

Sonal Devi (name changed), 23, a volunteer from Fatehpur, knows how to begin these conversations. “When we organise mohalla meetings, we give examples—and the biggest example I could give was mine,” she says. The youngest of seven siblings, with six sisters and one brother, she watched three of her sisters being married off while they were adolescents. Her own education was cut short after Class 8, and it took years of struggle before she could return to her studies. “It was a tough fight, but I pursued my education further. When I got connected to Educate Girls, it became very important for me. Today, when I look back, I can see people’s eyes gleaming when they talk to me. That is what I want other girls to feel too.”

Over the years, the organisation’s reach spread to over 30,000 villages. The numbers are staggering: two million girls re-enrolled, 2.4 million children reached through remedial education, and retention rates above 90 per cent. The true story lies in the images these numbers contain: the girl clutching her first schoolbag after years of staying away from classrooms, the father convinced after weeks of conversation to delay his daughter’s marriage, the sarpanch announcing at a village gathering that education was now a collective duty.

For girls above 15, beyond the reach of the Right to Education Act, another path was carved: Pragati. Here, makeshift camps were set up outside schools. Lessons in literacy and numeracy were stitched together with plays, songs, and role plays that offered practical lessons.

Pragati also confronted child marriage, still common in many parts of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.

Gayatri Nair Lobo, CEO of Educate Girls, recalls meeting a girl named Sapna in Dhar. “She said to me, ‘Sapna ko koi sapna nahi hota,’” Lobo remembers. The girl had been discouraged by her mother from dreaming of becoming an army officer because a woman shouldn't be nursing such ambitions. "It is only when you have someone to aspire to that it instills the feeling in you to do something,” Lobo reflects. The moment captures the quiet revolution Educate Girls aims for—the shift from resignation to possibility.

The organisation has big plans: to impact 10 million learners by 2035, expanding into new regions and perhaps even across borders where similar patterns of exclusion persist. Yet, even as it grows, its essence remains rooted in the smallest of victories: a door opening, a girl walking into class, a family daring to imagine a different future.

Today, in villages where girls used to be confined to their homes, there are signs of change. The silences in their lives have been replaced by new sounds—the scrape of chalk on slate, the chants of lessons repeated aloud, the laughter of adolescents rehearsing plays. Where once the burden of chores defined girlhood, now the promise of classrooms reshapes it. The work of Educate Girls shows that the walls of tradition and poverty, however tall, are not unbreakable. When communities lead, when girls are given the chance to return to school, when one dream becomes contagious enough to spark another, change no longer feels impossible