This is the cover story for Outlook's 21 September 2024 magazine issue 'Caste vs Caste'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

From time to time, the controversial issue of sub-caste reservation has been brought before the Supreme Court for its constitutional validity. In the recent case in 2024 the Supreme Court had to clarify whether the Scheduled Castes (SCs) constitute a heterogenous group, and, whether its sub-classification was permissible for sub-caste reservation. The Chief Justice of India (CJI) upheld the constructional validly of heterogeneous character of the SCs and the sub-classification for reservation to most backward sub-castes, to which all judges except one agreed. The other judges also made additional suggestions that include the exclusion from reservation of the creamy layer, and first-generation/one-time benefactory of reservation, economic criteria and time limit to reservation.

The judgement is justified both on constitutional and academic grounds. However, a close look reveals that the academic arguments were mostly based on assumptions without much empirical evidence, resulting in a weak academic justification of the judgement. We will therefore assess the validity of the judgement from only the academic point of view.

Judgement on Heterogeneity and Sub-classification

From the few available field studies, the CJI presented empirical evidence on untouchability within the sub-castes in taking food and water, use of wells, and temples, etc., as justification for the persistence of heterogeneity among the SCs. As can be seen, the evidence on untouchability is mainly confined to the “social/civil/religious” spheres, which undermines the dignity and citizenship status of some sub-castes. However, there is near absence of evidence on the differential treatment by one sub-caste against others in the economic spheres, in denial of right to property, business, employment and education. This implies that the case for sub-classification is mainly based on heterogeneity related to discrimination in the “social” spheres, ignoring the discrimination in the economic spheres, if any. It needs to be recognised that the discrimination in economic spheres matters the most in adequate representation and economic and educational development, than the dignity and citizenship-eroding discrimination in the social spheres. Therefore, the suggested policy of sub-caste reservation may have limited impact on addressing the problem of sub-caste inequality in representation and development.

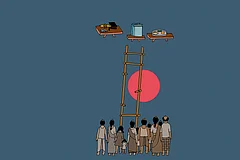

On this point, it would have been useful to draw lessons from Dr Ambedkar, who recognised the homogeneous as well as heterogeneous character of the SCs. It is homogeneous in so far as all sub-castes within SCs faced nearly identical discrimination in the social and economic spheres--a common thread of untouchability runs through all of them. The SC is heterogeneous because of untouchability between them. As back as in 1930, Dr Ambedkar, as a member of the ‘Depressed Classes and Aboriginal Tribes’ Committee of Bombay Presidency, in a chapter on ‘Untouchability Within Untouchables’ mentioned: “It must be admitted that a good deal of untouchability within untouchability exists in this Presidency.” The report based on a field survey found evidence on inter-sub-caste untouchability mainly in the “social/civil/religious” spheres, and much less in economic spheres. Dr Ambedkar, however in a presentation to the Southborough Committee in 1919 did emphasise the denial of economic rights to property, employment and education as an aspect of untouchability faced by all sub-castes. Because of this dual homogeneous and heterogeneous character of the SCs, Dr Ambedkar proposed a dual policy. A uniform Group Focus ‘policy of legal safeguards and reservation in legislature, public services and education for all SCs for adequate representation.’ Also, an Individual Focus ‘policy for economic and education empowerment of those individuals who are assetless/ landless and less educated within sub-castes.’ The purpose of complementary Individual Focus ‘policy for economic empowerment was to enhance the education level and in turn, the capabilities to access the jobs under reservation’. In the memorandum, ‘State and Minorities’ to the Fundamental Rights Committee in 1947, Dr Ambedkar suggested dual remedies, a Group Focus ‘Remedies against discrimination’, legal and reservation and individual focus ‘Remedies against economic exploitation’ though nationalisation of land, basic and key industry, and education.

From Dr Ambedkar’s perspective, the sub-caste reservation policy justified by the CJI may have limited impact in realising the goal of “substantive equality”. To bridge “inter-sub-castes’” gap in representation and in economic and education development, bridging the gap between the individual “within sub-castes” is necessary, failing which, Group Focus policy of reservation alone may restrict the reduction in inequality “between the sub-castes”. It follows that reservation to the sub-castes with keeping inequality with-in sub-castes intact may not ensure equality between the sub-castes. Therefore, the dual policy proposed by Dr Ambedkar may be a proper solution to pull up the most backward sub-castes. At no stage in the 37-year-long search for affirmative action policy between 1919 to 1950, had Dr Ambedkar proposed reservation within sub-castes.

Creamy Layer and Economic Criteria

Some judges moved beyond the mandate and suggested the exclusion from reservation of the creamy layer, and one generation and/or one-time beneficiary of reservation, including economic criteria. Judge Pankaj Mittal for instance, argued: “the experience shows that the better of the class amongst the backwards eats up most of the vacancies/seats reserved leaving the most backward with nothing in their hands.” Assuming this to be the case, Judge Bhusan Gawai recommended “unequal treatment to unequal classes” to achieve real equality and proposed exclusion of the creamy layer among the SCs.

Is this assumption supported by fact? Reality tells us that the reservation policy in fact benefited the weaker section among the SCs more. For instance, in 2022 about 89 per cent of SC employees in the Central government were in C and D categories, and the remaining 11 per cent in A and B. Direct evidence from the National Sample Survey on Employment 2022/23, revealed that around 78 per cent of government employees, Central and State combined, were from lower-income households and the remaining 22 per cent from top income ones. The share of lowest-, middle- and highest-income households in reserved jobs was 41.4 per cent, 36.5 per cent and 22 per cent respectively. In urban areas the share of lowest-, middle- and highest-income households was 30.7 per cent, 29 per cent and 22 per cent respectively. Their representation, however, was mainly confined to lower jobs due to low education. Thus, the assumption of Judge Pankaj Mittal of “cornering of most posts by economically better” was influenced by the myth created by academicians.

This myth has also led to the suggestion of exclusion of the creamy layer from reservation, with application of economic criteria. It is based on the assumption that economically better SC class “can walk shoulder to shoulder to higher caste.” Better economic standing is thought to be good enough for discrimination-free mobility. However, this view is not justified either in the theory of discrimination or empirical facts. The theory tells us that group discrimination is based on ‘group identity’, such as untouchability, the untouchables as a group face discrimination irrespective of the economic standing of individuals within the untouchables. Caste discrimination is neutral to economic status. The empirical evidence supports this theoretical assumption as discrimination is still very much alive, indicated by around 4 lakh atrocities cases from 1955 to 2022, which affected both the economically weak and the better off. Primary studies showed much wider discrimination in access to public amenities, employment, purchase of inputs and sale of output by SC farmers, and businesses, including discrimination against students in educational institutions. Studies also show greater discrimination in employment of persons occupying high posts. If Article 15 (2) guarantees that “no citizens shall on grounds only of caste, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction”, and if economically better SCs face discrimination, they would also need protection against discrimination through reservation. What can possibly be done is to exclude the economically better SCs from economic concession and various caste-based subsidies but not from job reservation.

One Generation and Time-bound

The suggestion to exclude those who availed reservation once/in one generation also lacks empirical evidence. We know that several SC students, and government employees and entrepreneurs, who face discrimination are second/third generation beneficiaries of reservation. Therefore, to assume that use of reservation for one generation would make SCs free of all caste disabilities is unsustainable.

Same is the case of the suggestion for “time limit” to the reservation. The time limit is necessary. However, it would depend on the extent of discrimination and the disparities between the SCs and high castes. Untouchability still persists in a worse form, even after 70 years of enactment of the Untouchability (Offences) Act of 1955. And the gap between SCs and high castes in all indicators of human development also persists. Therefore, reservation is necessary till untouchability and the gap between SCs and high castes in economic and education development persist.

Judge Pankaj Mittal also suggested replacement of caste-based reservation by alternative criteria as it induces casteism. Dr Ambedkar had replied to this argument by saying that the reservation by reducing inequalities between untouchables and high castes and also by bringing them together in legislature, executive, jobs and educational institutions, in fact minimises social isolation and prejudice and help to understand each other better and build up harmony.

Varna is Better than Caste

Strangely enough Judge Pankaj Mittal shared his personal faith in the Gita and the Ramcharitmanas, although the latter supports unequal status of Shudras and women. The Judge justified the varna system of the Gita, which favours grouping of Hindus in four varnas based on their innate qualities. Present knowledge indicates that qualities are never fixed, education and training can bring about change. To say that qualities are innate and fixed is to support the racist ideology propounded by Manu, which the Gita picked up. For instance, the Manu Smriti says, “A Shudra, though emancipated by his master, is not released from servitude, since that is innate in him, who can set him free from it.” Dr Ambedkar argued that it is the varna system which had given birth to the caste system.

The suggestions to leave the task of sub-classification to the State governments is equally problematic. At the State level, the political forces come in to play more forcefully than at the Centre, which is at a distance. In Maharashtra, in the Maratha reservation issue, quite independent of the fact that whether it is justified or not, political considerations come into play not only in electoral politics but also in the survey conducted to build up the case for Maratha reservation. All these go to show that the academic base of the judgement and recommendations is weak, which calls for a review of the judgement.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(Views expressed are personal)

Sukhadeo Thorat is Professor Emeritus, Jawaharlal Nehru University and former Chairman of the University Grants Commission

(This appeared in the print as 'Of No Consequence')