A Future of My Own

Today I carried my satchel again, the strap sliding down my shoulder as always. The bell rang, though it is not a bell, just the old iron plate our peon hits with a stick. Sometimes the sound is sharp, sometimes dull, but it means the same thing: time for class. I still run inside, even though I know our school might close any day.

I did not always know this. For years, Ma and Baba told me I was lucky to study in an ‘International School’. My parents and I belong to the Kathakari tribe. Our tribe is what is called a ‘vulnerable tribal group’. Many people from my tribe work as farm labourers and firewood sellers. Some are fishermen, others earn a living from coal- making and brick-manufacturing.

My school has a mural of a globe on the wall, which had bright colours once, but have faded now. The letters say ‘International’ in English, and I felt proud when I read it out loud. I thought it meant I could go anywhere in the world.

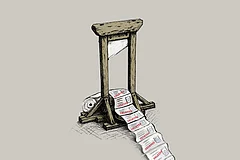

But last month, our teacher whispered to us that the government had put our school’s name on a blacklist. ‘Illegal’, they called it. Illegal, like stealing. I don’t know how a school can steal, but they say it is because it has no permission papers.

At night, I hear my parents (Anil and Anita) argue. They are worried about the fate of my shcool and my future.Baba says, “We paid the fees, more than what the government school charges. Why would they let it run if it was fake?”

Ma says she cannot even imagine sending me to a school ten kilometres away in Vaje. It would mean I leave home before sunrise and walk all by myself across the rugged hill path. They say the government will transfer me, but I don’t want to leave my friends, or this classroom with cracked tiles where I know every corner.

Sometimes, I try to imagine myself in the government school. I have seen it a few times myself . The school is a crowded place filled with children. There are benches made for two with three or four students squeezed in.

My cousin studies in the government school. He says that the teachers are good, but they are only a few, and sometimes there is no chalk, no water. Still, when he finishes Class 10, his marks will count. Mine may not. That is what scares me the most.

‘Smart’ Classes

I remember last week when our teacher told us, “Even if the school closes, you should not stop studying.” She looked sad, like she was about to cry. She is kind and she pays me compliments. She’s always telling me my handwriting is neat.

I wanted to ask her, if the school is illegal, are even her words illegal?

But I kept quiet.

Walking home one evening, I saw children from the village going to the anganwadi. They had small plates in their hands for khichdi. Sometimes, we get mid-day meals too, but the rice has stones in it, and the dal is watery. Ma says, “At least you eat.”

In Wangani, my friend Raju told me that they had no roof for three years during the rainy season. They sat in ankle-deep water and went on with their studies. I thought he was exaggerating, but then I saw the broken tin sheets piled up behind their school. He wasn’t lying.

When Baba was young, he says, he had to leave school. He stopped his studies after Class 3 so he could help in the fields.

Baba cannot read English. That is why he enrolled me here, because the poster outside said ‘Smart Classes and English Medium’. He thought it would change my life. I don’t know if it will. I only know that I like writing essays, and once I drew the map of India correctly and got a star.

The Bells Beckon

The other day, my little sister asked, “Will you still wear your uniform when the school closes?” I didn’t know what to say. Maybe I will. It is blue and white, and though the collar is torn, it makes me feel like I belong somewhere.

Sometimes, when I look at the mural of the globe, I imagine it glowing again, freshly painted, with no cracks. A school that is strong, legal and safe. A place where no one has to sit on the floor to study, where every girl has a bathroom, and where the food does not taste of smoke or grit. I don’t know if I will ever see such a school, but I hope I will.

For now, I will keep walking through the gate each morning, listening to the clang of the iron plate, pretending it is a bell calling me toward a future that is still mine.

(Sakshi is a Class 4 student. She is from Vaje, Maharashtra, and she belongs to the Kathakari tribe)