More than a century ago, in a court in Tura in the northeast Indian state of Meghalaya, a Garo tribal man filed a petition seeking compensation from his prospective father-in-law.

According to Garo customs of the time, when a local woman finalises a man for marriage, her uncles and brothers would abduct him. It was expected that the man would resist fiercely, yell and try to escape. This resistance was seen as a sign that he would be a strong and prosperous husband. If he offered little or weak resistance, it would not impress the woman’s family.

The man followed the tradition by resisting abduction, but was eventually confined to the prospective bride’s home. Tradition also dictated he should attempt to escape, which he did. If caught, he’d be brought back. However, a second escape would signal his unwillingness to marry, leading to the proposal being called off.

In this case, after the groom-elect escaped from confinement at the bride’s place, no one searched for him. The girl married another man who, according to Major Playfair, then deputy commissioner of Eastern Bengal and Assam, was “less strict in his ideas of Garo etiquette.” Feeling insulted, the original groom-elect petitioned the court, as recounted in Playfair’s 1909 book The Garos.

In Garo society, property is inherited by women. One can, therefore, understand why the wedding ball starts rolling after the girl or woman identifies a prospective groom. It was believed that the whole process spanned a few days to weeks, giving the man sufficient time to decide.

However, by the 1970s, this practice of ‘abduction marriage’, locally called chawarisikka, had become almost extinct, as Milton Sangma pointed out in his 1979 book History And Culture Of The Garos.

Chawarisikka is not the only tribal marriage custom that has gone extinct with time. There are several others. Some gave way to modernity in society, some came into conflict with new laws and some were engulfed by the advent of organised religions like Christianity and Hinduism, even as others were edged out by dominant ethnic cultures.

There was a custom among the Bhil tribe living in Gujarat called Gad-Gadheda or Gol-Gadheda, observed on the day after Holi and at a village fair. Unmarried girls or women would dance in an inner circle around a tall bamboo or wooden pole, which held atop, an earthen pot filled with jaggery and a coconut. They held brooms as they danced. Unmarried boys or men would dance in an outer circle around them.

Amidst the beating of drums, the male members would try to break the inner circle and climb atop the pole or a tree to grab the pot and the coconut, even as the assembled unmarried women would try to drag them down. Whoever got to the jaggery and coconut first, got to choose his bride from the inner circle.

In India’s tribal societies, influences from modern education, laws, Christianity, Hinduism, and Bollywood films contribute to the erosion of unique customs.

The festival is still celebrated in the Dahod district of Gujarat every year, but the winner no longer gets to choose his wife. There are other ways to find partners nowadays.

India’s tribal marriage customs and rituals exhibit diverse practices, varying between clans and villages. Some tribes engage in elaborate multi-day festivities, while others prefer simpler ceremonies. However, research indicates a trend towards homogeneity in recent decades. While tribal societies historically embraced various marital arrangements—including monogamy, polygamy, polygyny and polyandry—monogamy has become increasingly dominant. Additionally, the influence of organised religions has led to a shift towards more conservative views on sexual behaviour, impacting tribal traditions.

Traditional methods of sending marriage invitations, such as betel nuts and leaves or sun-dried rice mixed with turmeric, are being replaced by printed invitation cards. Hindu and Christian priests now officiate marriages instead of tribal shamans. Customs like mehendi and sangeet, traditionally popular in northern and western Indian Hindu societies, are gaining popularity among tribes in central or northeast India.

In his 2004 book Tribal Culture in India, Narayan Mishra mentioned that among the Korku tribe of central India, the bridal party used to place ‘literary’ obstacles before the groom’s party by confronting them with riddles. The marriage would take place only after the riddle was solved. But such rituals are also vanishing.

In a 2019 paper by Rajshree Shastri and Archana Kujur of Bhopal’s Barkatullah University, it was highlighted that economically affluent members of the Kurku tribe are adopting Hindu traditions to distinguish themselves from their community. Traditional attire like the Sehra, made of date leaves and covering the face and head, is also declining in use. Shastri and Kujur’s survey found that only 32 per cent of respondents preferred traditional attire in marriage ceremonies, while 68 per cent preferred kurta-pyjamas or shirts and trousers.

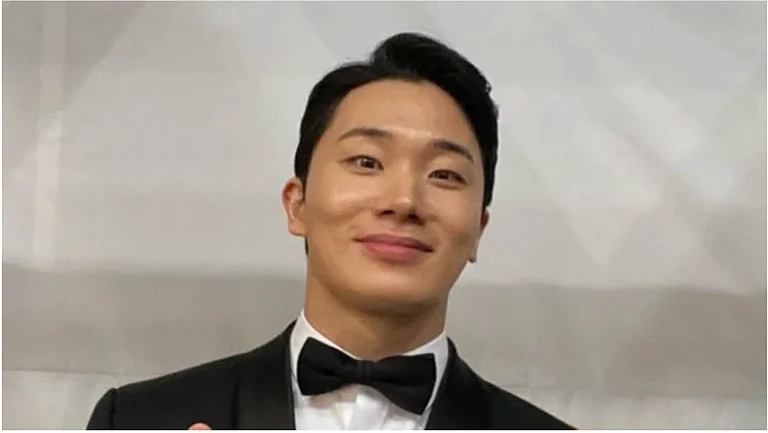

The Tangkhul Nagas of Manipur show a similar trend. According to a 2017 paper by researchers from Meghalaya’s University of Science and Technology sociology department, they now favour western or modified traditional attire. During weddings, the bride typically wears a white gown or white attire, symbolising purity, while the groom opts for a tuxedo suit.

Modernity brings the risk of dominant cultures infiltrating even the most secluded corners through TV, internet, and smartphones. In India’s tribal societies, influences from modern education, laws, Christianity, Hinduism, and Bollywood films contribute to the erosion of unique customs.

In the article ‘Changes and Emerging Trends in Lotha Naga Marriage System’, researcher Mhabeni W highlighted a shift from traditional marriage to Western practices, particularly white weddings in churches. “Now in most of the weddings, we see the influence of western culture, like the exchange of rings, a white wedding gown, cake, etc. which appear prominent in marriage functions,” said the 2023 paper.

Researcher Latika Besra noted in a 2023 paper that wedding ceremonies among Santals are evolving. Educated and employed Santals are increasingly eschewing the elaborate rituals of traditional marriage practices. In the Bankura district of West Bengal, financially stable Santals now opt for reception parties similar to those at Bengali weddings.

In the Reang tribal society of northeast India’s Tripura, the marriage feast was a community affair. Traditionally, it was held at the homes of neighbours, where guests would be put up. The bride or groom’s family would send raw meat to their neighbours, who would then cook it and serve it to guests along with wine.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

In his 1995 book, Anugatamani Akhanda observed a decline in the tradition of communal hosting of guests among the Reang tribe. Feasts were now primarily organised only at the house where the marriage occurred. Akhanda concluded that this shift indicated a decline in mutual understanding, particularly within the primitive Reang society.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Runaway Groom')