The 1994 family drama Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (HAHK) opens to a cricket match. The camera glides up to frame a mansion facing a ground. It’s decked with a pitch, wickets, and bails, rimmed by a white picket fence, spectators, and lamp posts. Without a line of dialogue, director Sooraj Barjatya establishes three key facts about the family: that it is rich, chic, and serious—or, well, ‘professional’—about having fun. A family that functions as a corporation. Everyone serves a fixed function in this scene (much like a job designation): the players wear golf caps that say “Boy” and “Girl”. The spectators move and cheer in unison, like coordinated robots. When a woman, a peripheral character, wants to bat, the hero, Prem (Salman Khan), mocks her and sends her away. Even though it’s a small, silly scene, it underscores the family’s ethos in precise details (confirmed by the rest of the film): that it prizes segregation and homogenisation, hierarchy and tradition.

For the next 214 minutes, the movie unfolds, in essence, as a “wedding video” (as it was lampooned in its initial weeks), where Barjatya inverts all the rules of a Bollywood blockbuster: no bloodshed, no conflict, no villains. Like a cola-dispensing machine, HAHK never runs out of sugar. Or affluence: its business-owning family is so rich that it has a swimming pool inside the house. Or consumption: gustatory pleasure is so ubiquitous that food appears across multiple scenes and songs (remember Chocolate, lime juice, ice cream, toffeeya?).

The gifts of economic liberalisation—or the lure of Western capitalism—pervade this family drama, sometimes straining to make a point. In an early scene, the domestic help Lallu (Laxmikant Berde), who is trying to learn English, holds a book upside down. What’s on its cover? Four letters in red: “USSR”. But Barjatya would only allow a certain kind of Western dominance; he’d temper it, in fact, with his fixation on Indian (actually, Hindu) culture. This is a film where the bride and the groom meet for the first time in a temple, where she gets the Ramayana as a wedding gift, where characters pray (and plead) to gods multiple times.

This cultural assertion isn’t just pious but also melodramatic, as every conceivable wedding ritual—the engagement, the tilak, the shoe stealing, the bidaai—produces a song. HAHK was so successful and influential that it set the trend for wedding dramas featuring pomp, opulence, and religiosity. Such movies had resolved the conflict between the mandir and the market, making the former as prominent as the latter. “Bollywood wedding is a specific class-based gendered response,” wrote Jyotsna Kapur in a 2009 research paper, “to India’s turn to neoliberalism.”

But Barjatya wasn’t operating in a cultural silo—even though his production house’s Nadiya Ke Paar (1982), which had the same story as HAHK, was a much modest fare—as plush Indian weddings trace a long history. “In the Ramcharitmanas [1.92– 1.102, 1.286 – 1.342],” writes Philip Lutgendorf in the paper ‘Ritual Reverb: Two Blockbuster Hindi Films’ (2012), “Tulsidas twice ‘interrupts’ the first book with multi-page descriptions of weddings that feature feasts served on golden platters as well as such non-Sanskritic rituals as women’s song sessions that mock the groom and his relatives.” Such descriptions, he adds, “have said to influence popular practice, even becoming, in some regions, a liturgical text to accompany weddings.”

Ramoji Film City in Hyderabad heightened the interplay between cinema and life, providing services such as “(cinematic) pre-wedding shoots” and “customised wedding sets (as if for the silver screen).”

Post HAHK, several NRI dramas revolved around weddings, even if we don’t remember them as such. Take the blockbuster Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995)—which tucks the word “bride” in its title—where the hero’s (Shah Rukh Khan) transcontinental journey, from London to Punjab, seeks to not challenge but assuage the patriarchal order. In Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), Khan and Kajol’s wedding, flouting parental order, sets the central conflict. Both Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) and Kal Ho Na Ho (2003), written by Karan Johar, derive their dramatic mileage from one protagonist facilitating the marriage of the other. Year after year, these films perfected the dance of tradition and modernity, following their progenitor’s footsteps. Just hear what Prem says when asked about the kind of wedding he wants: “arranged love marriage”. Love and arranged, East and West, unending capital and patriarchal control stitched a world unto itself: spend like a baron, pray like a priest.

Once these blockbusters had devised a language, subsequent movies—such as Mere Yaar Ki Shaadi Hai (2002), Hum Tum (2004), Yeh Jawani Hai Diwani (2013), and many others—wrote the script. And this script could be homogenised—tripping on uniform Punjabi bling—because Bollywood, too, functions like a family, a family of dynasts, who have little interest (or curiosity) beyond their own cultures. By then, it had also become a “culture industry,” according to film scholar Ashish Rajadhyaksha, defined by happy, feel-good dramas that underscored “family values” and “investment in our culture”.

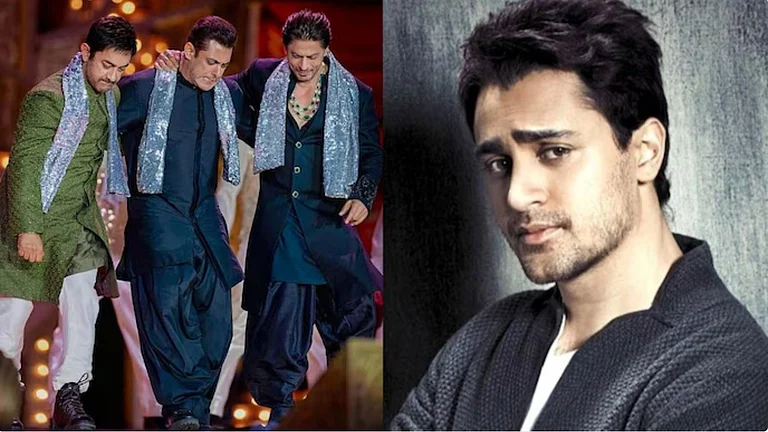

If popular Hindi cinema changed, then so did the conception of wealth among the Indian elites who, pre-economic liberalisation, felt sheepish to flaunt their riches. But in the aughts, money could buy you all—even a Shah Rukh Khan performance. This, too, became a trend, with other Bollywood stars entering the festivities (all at an appropriate price). The ostentatiousness of Indian weddings had reached such a high in 2007 that it compelled then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh—the architect of economic liberalisation—to comment on their “vulgar display of wealth’’ that “insult[ed] the poverty of the less privileged” and planted “seeds of resentment” among the “have-nots”.

Little did he know that the party had just begun.

Because if the Indian weddings could make the bride and groom feel like stars, then they could design appropriate ‘mise en scène’ justifying their Bollywood-fuelled narcissism. There was demand, and the flag bearers of ‘sanskaari capitalism’ swooped in. In the late aughts, for instance, the website IndianWeddingSite.com, writes Kapur, “encouraged their clients to watch Bollywood movies for inspiration, including designing outfits, staging festivities, and choreographing dance numbers”. And if that wasn’t enough, Ramoji Film City, a film studio facility in Hyderabad, heightened the interplay between cinema and life, providing a host of services, such as “(cinematic) pre-wedding shoots”, “customised wedding sets (as if for the silver screen)”, and “mesmerising dream venues”.

As real-life weddings became increasingly inspired by Bollywood—an industry known for its broad homogenised sweeps—they also began to look, feel, and sound the same. Because if popular cinema had shown only a sliver of Indian culture—chiefly Punjabi—then that’s what the masses could copy, making an India the India, drowning out local customs and contexts. This is what ‘cultural colonialism’ does: It makes you homeless in your own home. In the 1990s, for example, the sangeet ceremony was mostly part of a Punjabi wedding, but now it’s spread all over. My wedding too—which happened last month, an alliance between a Bihari and a Rajasthani—had a sangeet (and the juta churayi ceremony, where I paid Rs 9,000 for a Rs 3,000 shoe).

The recent Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant’s pre-wedding festivities—a dizzying confluence of business, cinema, and politics—finished in life what HAHK had unleashed on screen.

Two more factors, though, would alter this landscape forever, making us reach where we are today: celebrities and Instagram. Virat Kohli and Anushka Sharma’s wedding led the way in December 2017. It popularised wedding hashtags (#Virushka), lavender and pink frames, and professional videos (shot by Vishal Punjabi, founder of the production company The Wedding Filmer). Then came Priyanka Chopra-Nick Jonas (who sold their wedding photos to People magazine for $2.5 million), followed by Deepika Padukone-Ranveer Singh and Sidharth Malhotra-Kiara Advani (who hired the same director, Punjabi, as Sharma and Kohli). Often secretive about their weddings, stars release curated photos and videos for their fans on social media, influencing their choices, such as in decor, make-up, or mehendi.

By spending a huge sum of money, regular individuals can now marry like stars, and they make sure the world knows. Opulence has become meaningful, tied to an identity. This has inflated the cost of an average wedding, making desperation trickle down to the economically marginalised families who rely on loans to keep up. The pressure on Indian brides—irrespective of class and due to Instagram—is stratospheric. Before social media, we saw ourselves, and others saw us. But now, we see others seeing us, and we see ourselves seeing others. So the wedding becomes a quest for #GramWorthy perfection: the perfect lehenga, the perfect make-up, the perfect (sunset) shot. No one is immune from the last concern, not even Alia Bhatt, who, during her long wedding rituals, worried about losing daylight and, consequently, perfect pictures.

As weddings acquired the tenor of events—or performances—they moved from familial circles to service providers, exemplifying how the market overshadows the community. Because what once lay within the family—the preparation and execution of different functions, via parents, uncles, and aunts—has now been outsourced to wedding planners, choreographers, and photographers. With their Excel sheets and tablets and walkie talkies, wedding planners make intimate ceremonies resemble corporate events, and their demand has seen such an upsurge that it’s resulted in a critically acclaimed web series, Made in Heaven (2019, 2023).

With Indian weddings becoming larger than themselves—signalling financial might, networking power, and social status—they’ve culminated in what they were destined to be: political statements. Guest lists are no longer restricted to friends and families but hold in them a vast gamut of business and political possibilities. It wasn’t always like this. In the mid-1960s, the government ensured that a host couldn’t serve more than 25 people at home in a wedding. The various Guest Control Orders in the late 1960s and 70s continued to reflect a country in sync with its wallet and soul. Over the last decade, too, several bills (or proposals) have sought to restrain such excesses, but this India is different. It’s a country where money doesn’t just buy personality, money is personality.

And the recent Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant’s pre-wedding festivities—a dizzying confluence of business, cinema, and politics—truly finished in life what HAHK had unleashed on screen. It was an expensive celebration, yes (at a reported budget of $120 million), but that alone didn’t make it remarkable—or that it, once more, reduced Bollywood stars to dancing puppets. It was about what it showed and how—and whom it reassured and why. Sure, you expect an avalanche of Hindu iconographies at the wedding of two Hindus. But what explains a Muslim star, Shah Rukh Khan, greeting the guests with “Jai Shri Ram”? Or special provisions to make Jamnagar an international airport? Or the incessant fawning coverage, almost stopping short of displaying price tags of media houses? Besides, there was no condemnation of “vulgar display of wealth” this time but endorsement, as in January 2024, PM Narendra Modi encouraged moneyed Indians to “Wed in India”.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The Ambani pre-wedding, inviting both Rihanna and Sachin Tendulkar, coincided with a fresh wave of farmers’ protests. Three years ago, she had supported them on Twitter, while the cricketer, like many Indian celebrities, posted a tweet reminding “external forces” that, in Indian affairs, they should remain “spectators” not “participants”. The 2024 event, though, reversed their identities: Rihanna, performer; Tendulkar, spectator. It also gave a strange fillip to Indian identity, with many on social media pointing at it to proclaim national supremacy. It was a baffling equation—a business tycoon’s wealth became a poor country’s pride. But the most telling moment in the three-day extravaganza came when Merchant had to give a speech standing beside her fiancé. “Your life will not go unnoticed because I’ll notice it,” she said at one point. “Your life will not go unwitnessed because I’ll witness it.” Sounds familiar? It’s almost a word-by-word copy of Susan Sarandon’s dialogue from Shall We Dance? (2004). All the money in the world couldn’t buy a ‘heartfelt’ speech. It makes sense: After all, there are some things money can’t buy, for everything else there are electoral bonds.

(This appeared in the print as 'Band, Baaja, Business')