Summary of this article

Narayan’s Malgudi is built through language that quietly reproduces caste hierarchies rather than naming them.

A forgotten episode in Swami and Friends reveals how everyday speech enables social humiliation and violence.

Indian English fiction inherits caste logics from vernacular languages, shaping reader perception without overt politics.

Every English teacher would recognise the pleasures, the guilt and the conflict that is the world of teaching literature in a university. We are often carried away by the richness of poetry, be it when we are called upon to lecture about the elevated registers of Shakespeare or when we nurse creative ambitions and write some of our own unreadable verses. We are shocked by our own stasis in class, when eager ears await our interpretive moves while our inner demons, nurtured by what is happening around us, are roused and raging. We are usually remorseful as we make perfunctory remarks on grammatical infelicities when we know pretty well we aren’t engaging with what the student is trying to do in that paper. We walk into class holding inner conflicts, what to do when great art is created by artists who turn out to be terrible people, or what is the purpose of all these fictional worlds we enter and leave at will when the city is suffocating on polluted air, when the country is plunging into sectarian distress and the world is headed into an algorithm that rewards solipsism and narcissism.

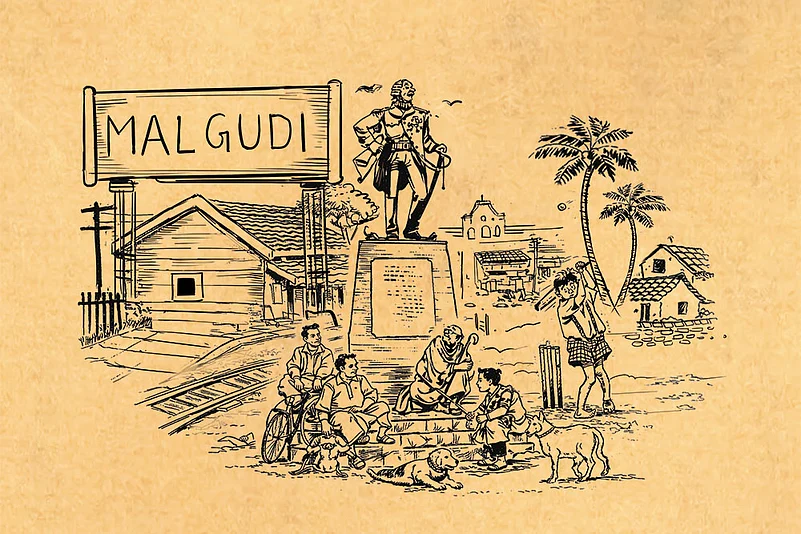

It is with such a contemporary and textured experience of teaching that R. K. Narayan introduces Krishna in his fourth novel The English Teacher. This is not to say that Krishna thinks about polluted Delhi in that 1945 novel, but that the world he inhabits, the world that Narayan conjures for us and we fondly co-habit with Krishna—Malgudi—does not simply remain a geographical literary canvas on which action occurs, it is a place that impinges on its characters to such an extent that their concerns and lives are so wholly realised and contained within. Quite literally, in fact, Malgudi’s pollution infects Susila, Krishna’s wife. Susila uses a lavatory that hasn’t been cleaned in a while, falls sick with typhoid and passes away. Krishna then goes to Tayur, a neighbouring village, to meet with a medium who helps him communicate with his deceased wife. The novel ends with Krishna realising he can have a personal communication with Susila without the need of the medium, and within Malgudi.

This move away from and eventual return to Malgudi, a motif we see in almost all of Narayan’s works, should make us wonder what powers this imaginative edifice conceals in its construction. If Malgudi is a motif, rather than ask ‘what is Malgudi’, we may perhaps better understand it as a literary reality and ask ‘how is Malgudi built’. After all, with each Narayan novel or short story, we would see Malgudi through several iterations, repetitions, developments, changes and fractures. But, if we were to ask how, we only have the language to look closely at—Malgudi remains a figment of imagination distilled in words strung together. And this new idiom, a language so fluid that it opened the floodgates of literary expression away from the English metropole, is Narayan’s significant contribution to the world of letters. But what is in that idiom that erected Malgudi into such an immediately recognisable Indian experience, a vision and way of life that related to the Indian subcontinent? Caste. Not caste as discrimination or hierarchy, i.e. as explicit casteist utterances, but as a willful forgetting of the everyday violence we perpetrate with language.

If Malgudi is a motif, rather than ask ‘what is Malgudi’, we may perhaps better understand it as a literary reality and ask ‘how is Malgudi built’.

Malgudi is first introduced to us in Swami and Friends, the 1935 novel with which Narayan burst into the literary scene and generations now counting among the adults experienced as a television series. When I speak of caste and Swami and Friends I do not intend an identitarian mode of reading the novel. That is, I do not want us to narrow our focus on the protagonist as a Brahmin boy, or take the discussion to how the story makes this small slice of caste society relate to all of society. Instead, we could look at the novel and think along with it. When Swami reminds him of the atrocities of the Mughals and their destruction of Hindu temples, Rajam, one of Swami’s closest friends, says, ‘We Brahmins deserve that and more’. And follows it up stating that his father does not observe rituals. While the publication year of the novel and Narayan’s own involvement in the non-Brahmin South India Liberal Federation’s mouthpiece The Justice sets Rajam’s rhetoric squarely within one anti-caste movement of the time, we can’t help but wonder what literary yield this rare political mention has for the story. Could it just be to add verisimilitude? A faintly registerable layer of acknowledgment over a politically sanitised novel about young boys, perhaps?

Let us look at another perplexing incident in the novel. Right about the middle of the novel, a seemingly unrelated episode begins the chapter titled ‘In Father’s Presence’. Swami and his two friends, Rajam and Mani, are sitting on a culvert when they see a bullock cart. They obstruct its path, and command the cart driver to stop. The driver is a little village boy, named Karuppan, younger than Swami. Rajam calls him a fool and screams at him. Swami threatens to arrest the boy. The young cart driver stops and asks, ‘Boys, why do you stop me?’ Mani asks him to shut up and investigates the cart. When the young boy pleads, ‘Boys, I must go,’ Rajam is infuriated. He senses condescension. In response, he says, ‘Whom do you address as “boys”? Don’t you know who we are?’ The trio heckle, torment and dehumanise the boy—they call the bullock he’s riding by his name. Why does this simple English word threaten these boys so much that they are not playing anymore, they’re engaging in serious violence? Now, this little village boy does not appear again in the story, and after recording this incident the chapter delves into a fascinating staging of Swami’s troubles with arithmetic problems in the presence of his father. Perhaps that incident is so forgetful and that is why decades of criticism hasn’t as much as even pointed to it, and the popular TV series even excised it from the screenplay. So, what does this incident do to our experience of comprehending how Malgudi is built word by word on the page? And, what if the word that excites so much passion in kids, ‘boys’, is not English at all?

If it is rendered in Tamil, the only other Indian language referred to in the novel, could ‘boy’ stand for the singular male suffix common in Tamil ‘da’? A close Hindi equivalent would be ‘re’. This suffix encompasses a range of affective registers in our everyday language and within the novel; it can be endearing (when Swami’s Tamil-speaking grandmother says ‘Come here, boy’) or authoritative (when Swami’s father says ‘Look here, boy. I have half a mind to thrash you’) or carries exasperation (when Swami’s father says ‘Here boy, as you go, for goodness’ sake, remove the baby from the hall’) or marked by tenderness (when a forest officer who rescues Swami says ‘That is right, boy. Are you all right now?’) or revulsion (when Rajam he tells off Swami who has run away from school for a second time ‘What a boy you are!’). Of all these affective registers, Narayan makes us see that in this instance the word ‘boys’ evokes anger because of perceived insult. Any older boy would get angry at a younger boy who addresses him disrespectfully. But where does the audacity to stop a child doing labour (i.e. not your schoolmate) come from? Where does the absolute certainty that dehumanising someone younger/less privileged than you, by stripping them of their name, come from? It is Narayan’s literary genius that enables us as readers to instantly subconsciously register this disrespect and stay within the narrative logic and not be ruffled. This feature in Narayan’s English, an idiom that encodes time-perfected registers of respect and disrespect that precipitates violence—and therefore is moved by a logic of caste—that is a common feature of our Indian vernaculars, is what makes Malgudi insidiously inclusive of our uniquely casteist language.

This article has not been about what to do when the art work we love turns out to conceal something terrible. It has been an attempt to explicate what it means to succumb to its beauty, attend to its artifice and ponder about what remains to be discovered beneath the sheets, about ourselves and our language.

Antony Arul Valan is a visiting assistant professor, Department of English at Ashoka University, Sonipat

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared as Only The Upper, No Lower Caste In in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘Party is Elsewhere’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.