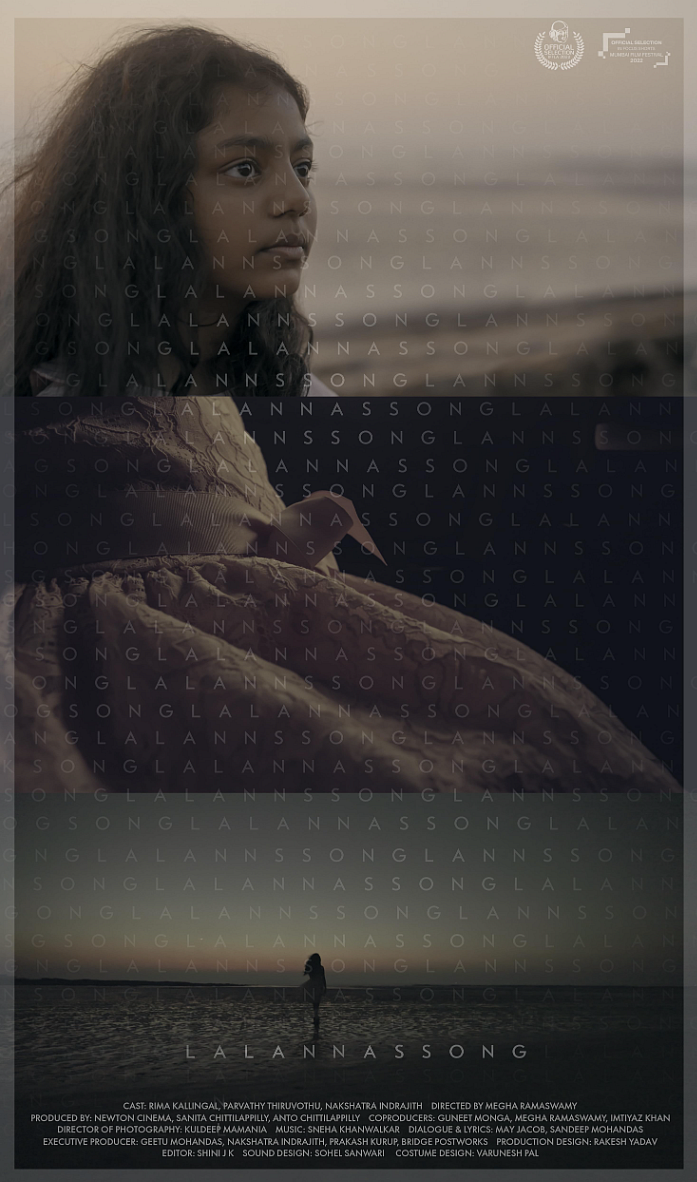

Megha Ramaswamy's Lalanna's Song (2022) started streaming on MUBI earlier this year.

The film looks at Rima Kallingal’s Miriam and Parvathy Thiruvothu’s Shoby.

Nakshatra Indrajith's Lalanna appears on screen and unnerves Miriam and Shoby.

There’s something spectacularly powerful about diverting the narrative of a story with the introduction of a genre shift. We have witnessed this in Bulbbul, the 2020 film by Anvita Dutt Guptan, where a drama beautifully unfolds to reveal the pulsating rage of its protagonist—and, by extension, the female audience she represents—in all its audacious and uncontained horror (read: glory). This narrative device finds a far more jarring representation in Megha Ramaswamy’s Lalanna's Song (2022), which started streaming on MUBI earlier this year. Rather than introducing this tonal shift towards the end of the film, Ramaswamy’s 34-minute short reveals an unsettling shot right as the film begins. Even as the narrative then backtracks to reveal a mundane day in the lives of two women and their children, one cannot but impatiently wait for the introduction of the titular character and her connection with the shaky first shot.

The drama foregrounds the irreverent chatter and authentic camaraderie between the women in the film, played by Rima Kallingal and Parvathy Thiruvothu. Lalanna's Song tells us little about Kallingal’s Miriam and Thiruvothu’s Shoby. They speak with each other in Malayalam and reside in Mumbai. Their conversations hint at a sequestered past dictated by societal and religious norms—the impact of which sustains via suppressed autonomy in their choices and behaviour, despite the absence of any disciplinary figure in proximity. While Miriam continues to self-police her attire, more out of habit rather than an active choice, Shoby appears beside her as a diligent friend eager to partake in acts of solidarity, the cost of which surreptitiously creeps up on her as the plot progresses.

Throughout the film, Shoby’s demeanour vacillates—from chirpy, playful and uninhibited to crude and at times appalled and uneasy—all depending on the context and the people she interacts with. Each interaction reveals much about how she places herself in society and how she has internalised its unsaid rules. Even as acts of beration manifest in the presence of less agentic characters, Shoby’s helplessness and subservience dominate the screen during moments of systemic violence broadcasted in the film.

Miriam, on the other hand, appears alongside Shoby as a calmer character. As a Muslim woman myself, I am always wary of representation in cinema. Having been caricatured as pitiful, unfortunate, hijab-donning characters dominated by the male figures in their lives, Muslim women in cinema only seem to find emancipation once they take off their head gear against uplifting music, with their blow-dried hair flitting across their faces. It is almost impossible to find a nuanced multidimensional Muslim woman in cinema whose concerns transcend the beatings of her surma-eyed husband and the panopticon policing gaze of her male relatives—both illustrating the image of the ‘bad Muslim’.

Ramaswamy’s Miriam seems to have developed an inherent fortitude over the years on account of her location as a minority in society. She retains poise in her demeanor and attire through most of the film, even in the face of systemic violence. Instead of publicising her innate desires, Miriam practices defiance against societal and religious norms in ways that are indulgent yet concealed—at times, even from Shoby. Beyond her proclivity for the bold and erotic, Miriam bears the latent potential of passing hurtful jibes and bullying those around her. In many ways, Miriam is a humanised grey character, flawed but full. She is not portrayed as a victim of the religion she was born into. However, despite humanising Miriam and further highlighting the oppressive and suspicious societal gaze through which she is viewed, Ramaswamy’s narrative still finds a way to get rid of the burqa, albeit as a matter of convenience and not as a means for emancipation. Such representation is hopeful, if not aspirational.

The duo’s interaction with the titular character, who enters the frame almost halfway through the film, almost unsettles the atmosphere immediately. Kuldeep Mamania’s cinéma vérité style cinematography palpably captures this tenuous shift, angling the camera to give the audience the impression that they are amidst the characters, standing next to the person being addressed. Enacted efficaciously by Nakshatra Indrajith, Lalanna appears on screen depicting attributes that are typically perceived as uncharacteristic, almost unnatural (or, perhaps even supernatural) of children. Lalanna unnerves Miriam and Shoby, who, despite their newfound agency in Navi Mumbai, still struggle to break out of their younger moulds and express their desires and aspirations in an assured, unencumbered fashion.

The contrast between Miriam and Shoby appears to exist primarily on account of their location in a stratified society. For an upper caste Hindu woman residing in India, the primary agents of oppression exist within her home, in the form of patriarchal figures. Beyond the domestic threshold, especially in a cosmopolitan city where anonymity is guaranteed, she imagines a utopian state of affairs, a place where narrow lanes and broad roads can be independently manoeuvred and religious markers can be sexualised without repercussions. For a Muslim woman—one who adorns identifying religious markers—utopia does not exist, especially in a country where she is not only a minority, but one that is a target of communal prejudices.

Even as Shoby and Miriam hold their own in conversations that they have with each other, the duo shapeshifts to function as a solitary unit when encountering people beyond their tight knit four-people unit. They tend to assert kindness, agency and compliance together. They also bear violence together and impart it together. Talking of violence, Lalanna’s Song is tainted with incidents of violence from the very beginning. Captured at a slow, meandering pace, the film illustrates their banal recurrence in everyday life and their continual acceptance by the victims and those around them.

A literal manifestation of the horror that such abuse and violence inflicts only manifests in the last act of the film, jilting the audience awake with accusatory lyrics sung against Sneha Khanwalkar’s unsettling music and camera jerks. As the film proceeds to a close, an innocuous little girl, innocent to the core, continues to remain blissfully oblivious to this diegetic horror, as if to illustrate the outcome that conscious shielding from abuse and psychological scarring can beget. As the film silently culminates into a banal sequence devoid of dialogue, this realisation holds a mirror to the audience, urging them to awaken and mindfully assess their own wounds, to heal and to not let these fester.

Almas Sadique is an architect, writer and journalist examining art, architecture, design and films through socio-political and cultural lenses.