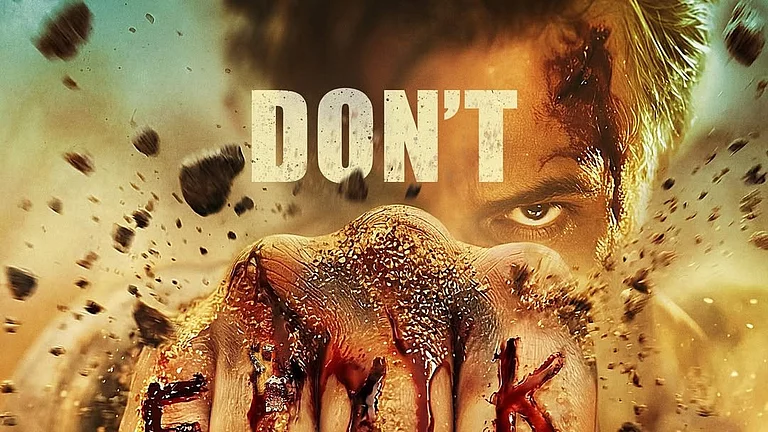

Kaantha (2025) is directed by Selvamani Selvaraj.

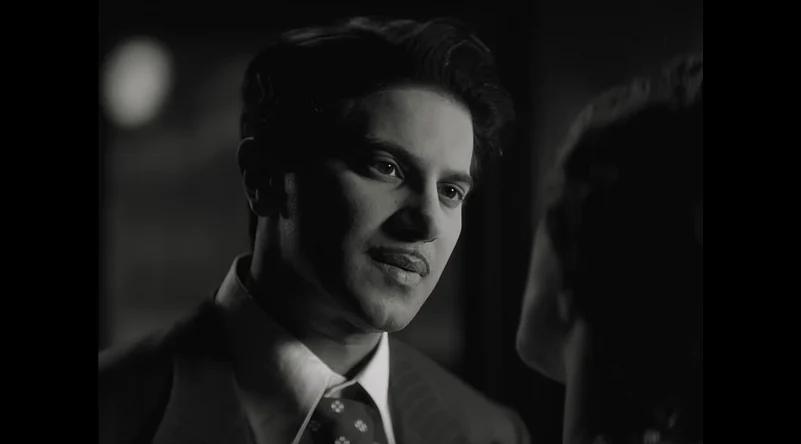

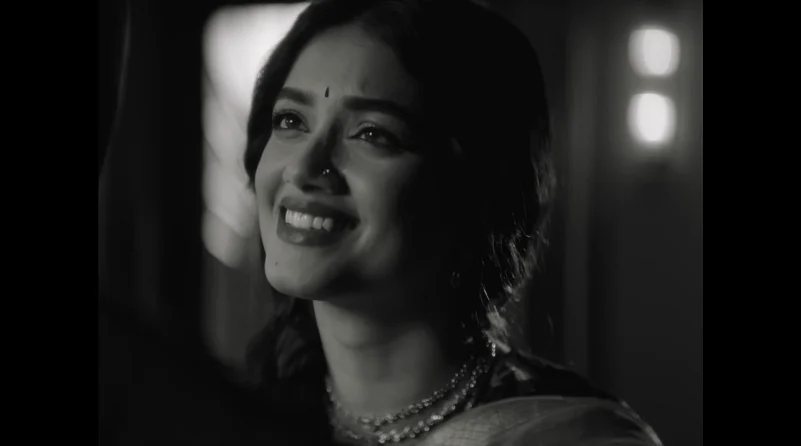

The film features prominent actors like Dulquer Salmaan, Bhagyashri Borse, Samuthirakani and Rana Daggubati.

Ayya, a legendary 1950s Madras filmmaker, navigates a complex friendship with his protege movie star TK Mahadevan as creative differences arise over a resurrected film production.

Cinema loves a resurrection, and Kaantha (2025) certainly enjoys staging one. Set in the buzzing, half-mythic vintage world of Modern Studios, Madras, the film pulls us into the 1950s and 60s with a cinematic reverence that feels quite ceremonial. The first sight of Ayya (Samuthirakani) returning to the dream he once abandoned for his mother is unexpectedly tender. And perhaps that is the artistic hook—a quiet metaphor for returning to what the heart still recognises, even when time has rearranged everything around it. His decision to revive “Shantha”, a film halted mid-conception, meets its first storm in actor TK Mahadevan (Dulquer Salmaan). Their sour history sits in the room like thick air, and Mahadevan’s decision to lead the film appears more like a tactical move to reassert dominance, rather than a homecoming. The film asks: who owns a story when egos outweigh devotion to the craft?

Enter Kumari (Bhagyashri Borse), Ayya’s newest discovery, obedient only to the director who mentored her. Her refusal to bow to Mahadevan’s whims sparks the first of many delightful skirmishes, yet she still manages to draw him in. Their romance blooms quickly, with the kind of innocence that almost tricks you into believing the film is drifting toward softness. A mysterious incident on set pulls Phoenix (Rana Daggubati) into frame, and suddenly the film behaves like it misplaced its own spine. Phoenix strolls in with investigative swagger, yet one wonders whether he walked into the wrong genre. The clash between Ayya and Mahadevan keeps circling, bruising, repairing, breaking again. Kumari tries to bridge the chasm, but the feud only grows teeth. Still, the idea of a film within a film finally inching toward completion carries a certain charm.

Kaantha’s first half is captivating, inviting viewers into the shimmering nostalgia of reel-filled corridors and clattering editing tables. Yet its extended black-and-white sequences test patience. They aim to deepen immersion but often resemble ornamental showreels disconnected from the tense drama simmering beneath. When the second half slows down gradually, the shift is rather jarring. The murder mystery hopes to elevate the stakes, though it thoroughly tends to elbow aside the emotional thread.

Technically, the craft stands tall. Ramalingam’s production design resurrects the era with attentive charm. Dani Sanchez Lopez, lights frames with a painter’s discipline. The period mood feels lived-in. Even so, the music disappoints, rarely heightening emotion and sometimes flattening it. The editing could use tighter shears, especially as the investigation meanders the emotional focus. The Telugu dialogues occasionally wobble, though the film’s visual grammar holds steady.

What ultimately saves Kaantha from its uneven pacing is the acting. Salmaan’s performance is a riveting portrait of a star battling ego, guilt, and desire. His eyes alone narrate an internal war he refuses to acknowledge. Samuthirakani counters him with grounded authority—their scenes sparking in ways the script often fails to. Borse plays Kumari with conviction and a quiet intelligence, and Daggubati injects a contemporary crispness into a retro canvas, even if his presence feels oddly placed.

Selvamani Selvaraj’s direction carries ambition, threading meta commentary on artmaking, power dynamics and the fraught relationship between mentor and protégé. Yet, ambition alone cannot conceal the soft spots. The pacing stretches scenes thinner than required, emotional payoffs stall and the investigation lacks bite. One wonders whether a more distilled narrative would have allowed the film’s strongest themes to flourish: the destructive allure of stardom, the fragility of artistic hierarchies and the ways women become battlegrounds in men’s conflicts.

Even so, Kaantha remains watchable, buoyed by its visual splendour and its compelling performers. It falters, yes, but it also holds moments that remind you why stories about filmmaking still entice us. Maybe it’s the irresistible chaos of the process of creation. Or perhaps it’s simply the pleasure of watching actors who understand exactly where the heart of their film lies, even when the script forgets.

Kaantha ultimately stands as a curious hybrid—equal parts homage, melodrama and self-reflection. It is imperfect, richly mounted, intermittently gripping and occasionally puzzling. The performances burn bright enough to hold your attention, but certainly not due to the storyline, which may disappoint those who know Selvaraj and Salmaan’s past work.