Laxmibai Kelkar founded the Rashtra Sevika Samiti on October 25, 1936, to provide women a space within the Hindutva movement.

The Samiti has around four lakh active members across 4,125 branches in India. Its projects include schools, health camps, and disaster relief, yet critics note tension between combat training and emphasising motherhood.

Tanika Sarkar argues that the Samiti empowered women only within traditional domestic roles, using communal mobilisation during the Ram Janmabhoomi movement to reinforce conservative gender norms.

Suvarna tightened the pleats of her saree, her movements precise. There was no time for idle chatter, her eyes fixed on the task at hand. Around her, vessels clattered as she garnished food, preparing offerings for the ancestors.

The calendar nailed to the wall was not Gregorian but a Hindu panchang (almanac), marking the last day of pitra paksha, a fortnight dedicated to remembering one’s forefathers. She had been taught that during this period, the veil separating the living and the departed thins out, and in that brief interlude, ancestors watch over their families, awaiting offerings.

It was a Sunday, a reprieve from her responsibilities as director at Wardha Nagrik Bank. And yet, in Wardha, Suvarna is better known as the pramukh (head) of the Rashtra Sevika Samiti, a role that intertwines her personal life with the organisation’s mission of nurturing Hindu women as pillars of the nation.

Nothing detracts Suvarna from the duties entrusted by the Samiti. On Monday, with Navratri sthapan arriving early, she walks nearly a kilometre to the Ashtabhuja Mandir, a temple said to have been sculpted under the guidance of Laxmibai Kelkar, who founded the Samiti on October 25, 1936, amid the growing tide of nationalism. This founding moment was no accident; it emerged from Kelkar’s determination to create a space for women within the broader Hindutva ecosystem, inspired by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), established in 1925. Kelkar, widowed at 27 with eight children, had approached Hedgewar seeking involvement for women in the RSS, but he advised her to form a parallel organisation. Thus, on Vijayadashami in Wardha, the Samiti was born, emphasising women’s roles in cultural preservation and national service, distinct yet complementary to the all-male RSS.

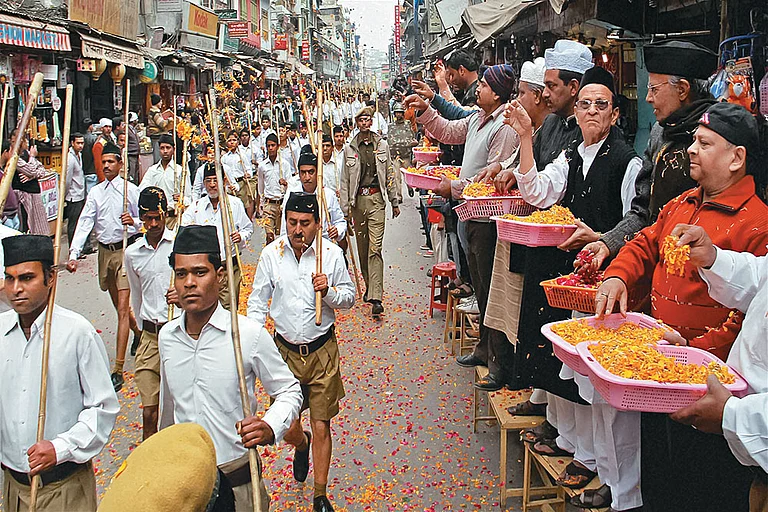

Affectionately called mausiji, her vision was to empower Hindu women through self-defence, cultural education and service, but within the bounds of traditional values. Over the decades, the Samiti grew into the world’s largest Hindu women’s organisation, with a presence in 5,216 centres across India and affiliates in ten countries. It operates 875 daily shakhas, where women and girls learn yoga, music, dance, cultural values, discipline and martial skills like lathi (stick) fighting and even swordplay.

At the Ashtabhuja Mandir gates, Suvarna is joined by dozens of women in sarees, gathering in disciplined rows under the saffron banner of dharma. She begins with the prarthana samaroh, leading the shakha, and calls out twice: “Hindu Rashtra!” The chant echoes through the air, a rallying cry for a unified Hindu nation. Among those standing in line is Aparna Hardas, a senior sevika in her fifties, her voice steady as she recites hymns. For the next six hours the women will remain at the temple, studying, singing and revisiting the words and legacy of “mausiji” Laxmibai Kelkar. “I joined the shakha because my mother-in-law was associated with it,” Aparna says. “This is about carrying forward the legacy. We do the Samiti’s work out of joy, not compulsion. And when your daitva (responsibility) increases, you are sometimes sent to travel, expenses taken care of. That too is service.”

As part of the outreach, sevikas travel across Maharashtra’s eastern belt, persuading women from other villages to join the Samiti’s shakhas. “Leadership positions here empower women to find their voice. They learn responsibility not only towards the Samiti but also towards nation-building,” she explains. However, scholars like Paola Bacchetta argue that this apparent empowerment is deeply constrained. In her book Gender in the Hindu Nation, Bacchetta notes that women from the Samiti produce a “specifically feminine discourse of the nation, which, at times, has ‘zones of convergence, of antagonistic divergence, complementary difference and antagonistic difference’ with the male nationalist discourses”. This discourse, while allowing women to negotiate agency, ultimately reinforces upper-caste Brahminical patriarchy, where women’s roles are tied to family and nation without true autonomy.

Suvarna, scanning the thirty-odd women assembled, ensures that every directive of the shakha is followed with precision. The day begins with prarthana, chants of Hindu dharma and lessons in flag-hoisting, though it is not the national flag but the bhagwa dhwaj (saffron flag) that is venerated.

This symbol, representing Hindu pride, is central to the Samiti’s activities, evoking a sense of cultural unity. “What does it mean to be Hindu?” is a question repeatedly posed to the younger sevikas. “It is not just a religion,” one of them responds. “It is a way of life, a rhythm of existence. There is meaning behind the bindi we wear, scientific reasoning in our earrings, and a sanctified space for womanhood itself.”

The Ashtabhuja Mandir, inspired by Kelkar and dedicated to the fourth incarnation of Durga, the cornerstone of the Samiti’s resolve, was adorned with lights and red garlands on Vijayadashami.

“The work she did could not have been done by anyone else, I believe. Her husband died when she was just 27,” said Aparna. Kelkar’s life was a testament to resilience; she travelled extensively, regretting only her lack of English proficiency, which she compensated for by insisting her family engage with global news, she explains.

Her grandson, Madhav Kelkar, recalls her with awe. “She barely stayed home, always travelling. She regretted only one thing—that she didn’t know English. It kept her from engaging in certain spaces. That’s why she insisted my father read The Times of India every day. And this was in the 1970s.” He pauses, then smiles: “Even now, the hymn she wrote—Namo Vam Matri Bhumi—flows on the lips of the sevikas.” But interestingly, neither her sons nor grandsons became actively involved in the Sangh Parivar, hinting at a curious separation between family legacy and organisational commitment.

The Samiti’s ethos is clear: “Our birth is destined for the nation. We may not be able to devote ourselves as Savarkar or Tilak did, but even a single effort to strengthen the community matters.” This philosophy draws from Hedgewar’s vision but adapts it for women, focusing on cultural and social roles rather than direct political action. For Aparna and Suvarna, this commitment is not symbolic, but a lived experience. After Navratri, women from Wardha will disperse to other towns, on instructions passed down from the higher leadership. “If a younger sevika organises a shakha, we listen,” Aparna notes. “Hierarchy is not about age but about responsibility.”

The organisation describes its mission through three guiding ideals: matritva (universal motherhood), kartritva (efficiency and social activism) and netritva (leadership). Rooted in safeguarding Indian culture, the Samiti runs 475 projects, from vocational training to health initiatives, positioning Hindu women as leaders and agents of reform in family, community and nation.

However, feminist scholars question this narrative. Tanika Sarkar, historian at Jawaharlal Nehru University in her analysis of the Samiti’s role in the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, critiques how it mobilised women through communal activities but confined their empowerment to “conservative domesticity”. Sarkar argues that the organisation uses figures like Savitri, a symbol of loyalty and sacrifice, to restrict women to roles as wives and mothers serving the Hindu nation.

The Samiti has around four lakh active members across 4,125 branches in India. Its projects include schools, health camps, and disaster relief, yet critics note tension between combat training and emphasising motherhood. Bacchetta further elaborates that women members of the Samiti subvert the RSS’ notion of them as “chaste mothers” by positioning themselves as “protectors of society”, but this agency is limited, as the organisation’s name lacks swayam (self), implying a woman’s identity encompasses family and nation over individual autonomy.

Coincidentally, Wardha carries another legacy that has endured through the decades.

Over the decades, the Rashtra Sevika Samiti grew into the world’s largest Hindu women’s organisation, with a presence in 5,216 centres Across India.

Just a few kilometres away lies Sevagram, Mahatma Gandhi’s ashram, where he lived from 1936 until his death in 1948. This proximity fuelled mausiji’s zeal. Laxmibai Kelkar admired Gandhi’s ideals of social upliftment, self-reliance, and moral service to the nation. His vision of Sarvodaya and emphasis on purity, simplicity, and truth inspired her belief that real change begins at the grassroots, with women as key agents of moral and social transformation. She launched efforts to operate as many shakhas as possible, countering what she saw as Western-influenced liberalism. In contrast to Gandhi’s emphasis on non-violence and inclusivity, the Samiti focused on disciplined Hindu revivalism. Daily shakha activities reflect this: mornings start with physical exercises, including yoga and games, followed by intellectual sessions on Hindu scriptures, history and current affairs. Women learn self-defence techniques, such as handling lathis or basic karate, ostensibly to protect themselves and their culture.

These shakhas serve as community hubs, where women discuss family issues, organise festivals and undertake seva (service) like blood donation drives or environmental clean-ups. In Wardha, shakhas often include storytelling sessions about historical figures like Rani Lakshmibai or Ahilyabai Holkar, inspiring participants to see themselves as modern warriors. However, academics like Irfan Engineer, through his work with the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, view this as a “masquerade”.

Engineer argues that the organisation’s emphasis on kutumb vyavastha (the family system) prioritises patriarchal traditions over equality, using the rhetoric of empowerment to mask subordination. He adds that the absence of the term ‘swayam’ (self) from the Samiti’s name—unlike the RSS— speaks volumes. This contrast underscores how the Samiti’s notion of women’s empowerment remains deeply tied to reinforcing traditional gender hierarchies rather than challenging them. At the flag shakha in Ahilya Mandir, the heart of the Rashtra Sevika Samiti, it becomes clear that the organisation is not merely a wing of the RSS but functions as its parallel. Here, the women sit with Chitra didi (Akhil Bhartiya Sahkaryavahika), who has devoted her entire life as the Samiti’s pracharika. She is a guardian to nearly 40 girls, native to the Northeast, who are being nurtured under the Samiti’s fold.

“This is a place they can call a haven,” she says. “They go to the New English School, return, eat, sleep, play.” The Samiti runs 30 hostels across India, housing around 6,000 girls. The Ahilya Mandir is one of them, focusing on girls from Assam, Tripura, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. “They are Hindus,” explains Poonam tai, a senior sevika. “You see the condition in the Northeast—mostly Christians. If there are a few Hindu households, attempts are made to convert them as well.” This outreach began in the 1980s, aiming to integrate tribal communities into mainstream Hindutva, providing education while instilling cultural values.

Girls can arrive here as young as four and stay until their education is complete. Two girls, for instance, have finished their studies but still live here—one pursuing fashion design, the other preparing for the civil services. “A lot of children here who are now in class 10 or 12 dream of cracking the state public service commission exams, and even the UPSC,” says Nagthong (name changed), who has completed her graduation. “It will help us develop our land and instil the values we have gained here. In my village, there are only twenty Hindu houses and no temple.”

Historical context adds layers: in 1840, Reverend Miles Bronson wrote about conversion challenges in the Naga highlands. A century later, Christianity became central to Naga identity. Today, amid Hindutva’s rise, Naga leaders urge safeguarding their faith. Poonam tai adds: “These children are tribals. They worship nature. But they also need a form—a space—to worship within.” Critics argue such initiatives reflect cultural assimilation, imposing Hindutva on tribals amid concerns over indigenous identities in “Christian states” like Nagaland.

Miati (name changed), the newest entrant, is just five years old. Almost all the girls studying in class 10 or 11 had joined the Samiti fourteen or fifteen years ago, when they were toddlers. “Rona toh aata hi hai (we did cry),” one of them says, recalling her first day away from home.

“But I believe this is a better place, and we have come here for a purpose.” Most children arrived because someone from their village was associated with the Samiti or had studied here before. “My aunt was here,” Nagthong adds.

“We are allowed to go home only once in two years,” one of the enrolled girls explains, “and the rules of the Ahilya Mandir guide every aspect of our day.” The schedule begins with shakha at 5:40 am. Prayers, flag worship, yoga and exercises follow for inmates, before a few playful games in the courtyard and finally dispersing to their respective classrooms. Among the throng of Northeast girls, visible in their diversity, one stands strong; she is not among the students. She is a pracharika.

Aditi Rajput (name changed), 25, from Rajasthan, speaks with quiet pride. “I knew there would be challenges,” she says, “but the shakha inspired me. I grew in discipline and purpose. After school, I worked in Jaipur, now in Nagpur. Like Chitra mausi and Poonam mausi, I have chosen a life as a pracharika and will not marry.”

Poonam Gupta (Kendriya Karyalaya Pramukh), herself had come from Jammu. Her interest in the Samiti developed when she was eighteen, after visiting the shakha near her home. In 2014, she began working full-time for the Samiti in Delhi. “I do go home occasionally, but the Samiti has become a bigger home for me now. These are children we nurture and guide in every possible way,” she says. Chitra sits in her white saree, the standard attire of the Samiti; white with pin borders. “Women play a very important role,” she says. “They are the foremost nodal figure of society: a mother. The sanctity of the Samiti is built around this principle.”

Tanika Sarkar, argues in her book The Woman as Communal Subject the Samiti fosters a “communalised female subjecthood”, confining empowerment to conservative norms, excluding women from RSS leadership, and channelling activism into protecting “Hindu honour”, she says citing Sadhvi Rithambhara, the fiery founder-chairperson of Durga Vahini, the women’s wing of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP).

Irfan Engineer views the Samiti as perpetuating patriarchy under empowerment’s guise. Critiques highlight opposition to “Western feminism”, with quotes like “Purush ka hai bahar ka kaam karna... Stritiya, matritav ka gunn hai (It is the responsibility of the men to work outside of home, femineity is embedded in motherhood)” emphasising rigid gender roles. Engineer’s work on communalism critiques how the Samiti’s campaigns like “love jihad”, control women’s choices, masking subordination.

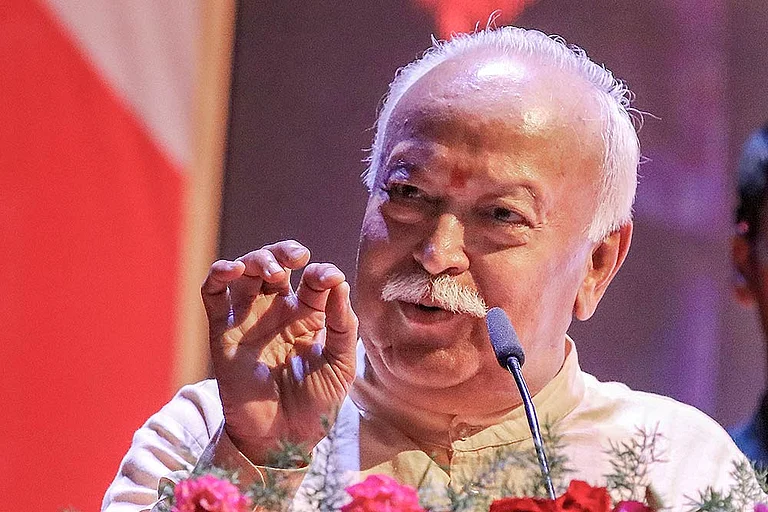

“The gendered construction of the Hindu Rashtra necessarily puts women in a subordinate position. Women are exalted by the RSS as goddesses and Bharatmata, but these are empty facades. There is no empowerment since this façade allows patriarchy and patriarchal structures which oppress women to go uncontested and further reinforce them,” he said. Highlighting hypocrisy, Engineer contrasts RSS sarsanghachalak Mohan Bhagwat’s 2019 statement vis a vis the Samiti’s practices, such as opposition to women’s inheritance rights and denial of marital rape. “There is nothing called marital rape. Marriage is a sacred bond,” Bhagwat was quoted to have said.

Engineer further argues that the Samiti promotes “motherhood” to counter demographic fears (e.g., urging more Hindu children) without addressing the critical issue of inequality.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Pritha Vashishth is Outlook’s Mumbai-based correspondent.

This story appeared as 'One Hundred Years Of...The Other Half' in the print edition of Outlook magazine’s October 21 issue titled Who is an Indian?, which offers a bird's-eye view of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), testimonies of exclusion and inclusion, organisational complexities, and regional challenges faced by the organisation.