Women in the Ramayana embody leadership, resilience, and protest but remain sidelined in male-dominated retellings.

Alternative versions, especially folk and Dalit tellings, place Sita at the centre while diminishing Rama’s role.

Across oral and written traditions, the many Ramayanas reveal women as visionaries, rebels, and change-makers.

Vijayadashami, popularly known as Dussehra, is celebrated each year to symbolise the eternal victory of good over evil. Observed on the tenth day of Navratri, Dussehra marks the triumph of Lord Rama over the demon king Ravana. While this spirit of victory lies at the heart of the Ramayana, the stories of its women characters often remain underrepresented.

Retellings and adaptations of the Ramayana remain popular across India, where each iteration of myths adds or creates a new version, a new protagonist, changes the lens, and changes the plot, too. However, the role of women and the gaze it employs is predominantly male-driven.

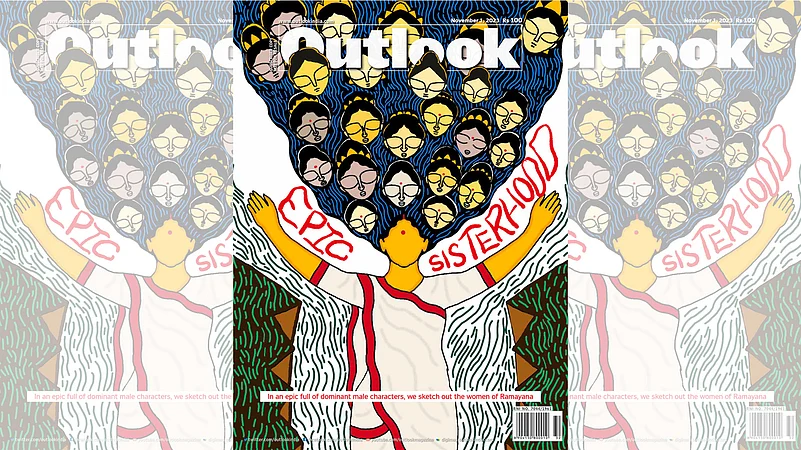

In Outlook magazine’s November 1, 2023, issue, Epic Sisterhood, we looked at the women of the Ramayana as an interrogation of dominant narratives. Retelling, an interventionist approach, is to bring out these other voices, these other stories.

In Devi Vs Rakshasi: The Portrayal Of Women In Ramayana, Mainin J A nandani looked at how the women of Ramayana seem to have been discriminated against, based on their birth, gender, origin, and political belief or background.

Many of us are even unaware that, apart from the popular Valmiki and Tulsidas versions, there are different narratives written by women. We don’t come across enough titles that narrate the Ramayana from a woman’s perspective, probably because we were so focused on deifying the central male characters that somewhere we may have neglected the female characters of the epic.

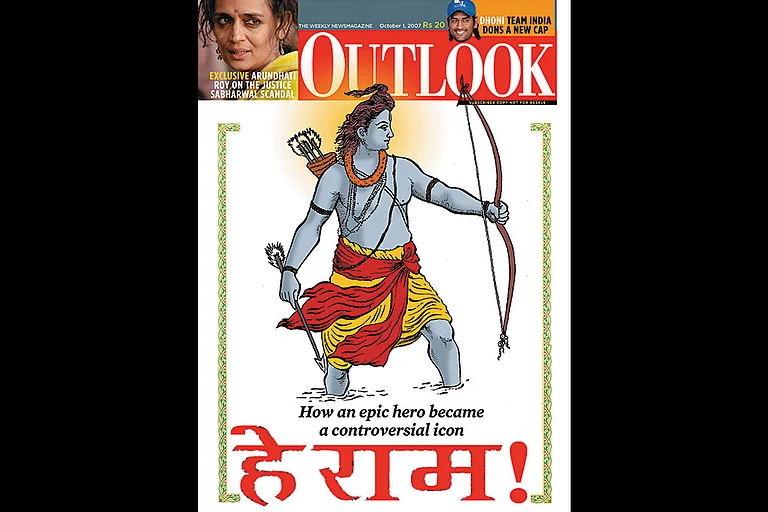

Much like history, mythology, too, can be a bit of a men’s club. Some popular versions from the 16th century have inadvertently incorporated the impact of socio-political influences of their times with regard to the status of the women in the story, viz. The ‘Lakshman Rekha’ incident, which although was not a part of the original manuscript, has now become a metaphor for women, thereby circumscribing their conduct.

However, Women in the Ramayana also inspire fascinating leadership trends. In Women In Ramayana: Tapasya Of Epic Change-Makers, Koral Dasgupta highlights that while popular narratives have viewed tapasya in the form of predominantly male fancy, women’s culture in Indian epics reflects upon it as brave contemplations by fierce change-makers. The Ramayana (and also the Mahabharata) shows an interesting trajectory of feminine leadership with abundant kindness, progressive decision-making, constructive protests and furious fights.

Sita, for example, comes across as a visionary who is not afraid to take risks. She is a loving soul, longing for the company of her husband, which adds to her tendency of romancing risks! It shows in her decision of moving to the forest when Rama is exiled. Her suffering does not make her risk-averse. When Hanuman comes to Lanka and offers to carry her back to Rama, she refuses. Yet another leadership idealism, which believes even in the face of adversity that deception is Ravana’s trait; it is not for her to hide and run. This decision marks her growth from a woman with innocent excitement to the future-queen now representing her country, unwilling to bow before fears and waiting to witness a befitting punishment of the enemy who has crossed both moral and geographical boundaries.

Sita, in this context, is considered revolutionary in several retellings. In Karnataka, Sita takes the centre stage in retellings of Ramayana and Dussehra. In Contesting Narratives By Retelling Mythologies From The Female Lens, Anisha Reddy explains how Sita doesn’t need her Ram. He’s not her hero. She saved Ayodhya from bankruptcy by using just pumpkin seeds. Mahishasura was killed by upper-caste Aryans and not Goddess Chamundeshwari.

In Karnataka, alternative retellings of stories from the Ramayana and about Dussehra steer clear of the narratives promoted by mainstream Hindu nationalists. Sita, and not the victor of violent battles, Ram, takes centre-stage in one famous Ramayana version told across Karnataka’s villages. Narrated specifically from Sita’s perspective, this version features Ram as a relatively diminished character. This Sita is one who carries out her daily tasks, cooks for her loved ones, even as she questions: “I say this not with sadness or anger. One day, the throne you sit on will pierce you, and to Mother Earth you will also return.” This is the essence of Sanntimmi’s Ramayana, a version told by a Dalit woman worker, created by Dalit writer, activist Du. Saraswati.

Different renditions of the Ramayana offer a different narrative of the epic. In Varied Narratives Of The Many Ramayanas, Azeez Tharuvana points out that there are umpteen social and cultural makeovers of Rama and Sita. Texts and subtexts differ from author to author, akin to the oral traditions. All major characters, including both Rama and Sita, are portrayed as kaleidoscopic incarnations in various texts/oral narratives with revamped colours and characteristics. As a matter of fact, all such oral/verbal narratives are nothing but tiny tributaries destined to merge into the larger river called the literature of the Ramayana.

For instance, a Kannada folk ballad collected by Rama Gowda states that Sita is the daughter of Ravana. And very ironically, it is Ravana himself, not Mandodari, who conceived Sita! He becomes pregnant after deliciously eating a sweet mango presented by Shiva. The ballad chronicles in detail the gradual development of his pregnancy, the pain and shame he suffered in those days and the incredible delivery of baby Sita through his sneezing. According to this version of the Ramayana, Ravana is a wicked wanton who even lusts for his own daughter.

Sita’s birth, growth and death are depicted in different designs in the folk versions of the oppressed castes’ Ramayana. Nonetheless, Sita is one of the most favourite characters for the folk singers. It may be assumed that they would have sung the hyperbolic episodes of Sita’s life with poetic endowments, emphasising the emotional and sensational segments to enthral the audience, which gradually might have become seasoned interpretations and beliefs.