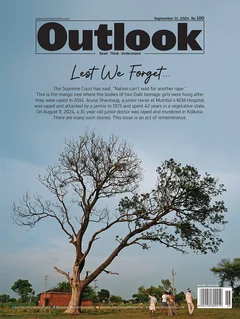

This is the cover story for Outlook's 11 September 2024 magazine issue 'Lest We Forget'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

Rubabdar, a Marathi word which translates to intimidating, is how Vaishali Gawde, the former matron, remembers the aura of the late staff nurse Aruna Shanbaug at King Edward Memorial Hospital at Parel, in Mumbai.

Her dashing personality was offset by a sharp tongue and short temperament that simultaneously commanded admiration and respect from colleagues, patients and passersby.

“When she would go on the rounds in the hospital, strutting her way, we would be awestruck and intimidated at the same time. She was a strict disciplinarian, a stickler for rules, who would not tolerate any nonsense,” Gawde recalls of her senior colleague when she joined KEM as a nursing student in 1969.

Four years later, on the morning of November 28, 1973, as Gawde entered the sprawling hospital premises to begin her duties in the main building, she was shocked by what she saw and heard.

Shanbaug had been found by cleaners in a distressing state—lying in a pool of blood, naked, with a dog chain around her neck. “We could not believe that someone like Aruna could be violated like this by a class IV employee. We all worked as a family and as a team, going on rounds together and checking the security of all buildings. It was terrifying to learn what had happened to her,” Gawde recalled.

The previous evening, 25-year-old Shanbaug was brutally attacked by a male sweeper, Sohanlal Valmiki, who raped and sodomised her, while strangling her with a dog chain in the basement of the Cardiac Vascular Thoracic (CVT) building. After the assault, he left her there with the chain still around her neck, cutting off oxygen to her brain. This led to a brain stem contusion, cervical cord injury and cortical blindness. The severe injuries left Shanbaug in a vegetative state, unable to move or speak.

The CVT building housed the now-defunct dog surgery research laboratory, where medical and surgical experiments were conducted on canines before being performed on humans.

Just days earlier, Shanbaug had discovered that Valmiki, a temporary contract worker, routinely stole mutton from the dogs' food supply. “She had a big quarrel with him and scolded him in front of other staff, threatening to sack him if he stole again. It seems she told him he would die like a dog if he continued stealing their food. He did not take this humiliation well,” Gawde learned from discussions with staff members.

On the evening of November 27, after finishing her duty, Shanbaug was allegedly caught by Valmiki while changing her uniform on the ground floor of the CVT building. This area, being a daytime department, was rarely visited by security guards in the evening. The hospital still followed British-era rules, requiring nurses to mark their attendance in their uniforms before heading to the residence hostel. Shanbaug had recently become a non-residential nurse as she was preparing to marry a KEM hospital doctor.

Until her death in 2015, Shanbaug remained a living symbol for KEM’s nursing community and influenced training of young nurses.

“We don’t know why she was alone at the CVT building, with no female staff with her. Perhaps, she was changing her uniform in a hurry before going home. Whatever the circumstances, it was extremely unfortunate,” Gawde says.

Following the matron's directions, Gawde and her colleagues refused to report for duty and went on strike, demanding better protection for medical staff and proper treatment for Shanbaug. This was the first time a nurse or any medical professional had been sexually assaulted on hospital premises by a staff member. The shocking incident led to the country's first nurses' strike, calling for stringent rules to prevent violence against healthcare workers while on duty.

Shanbaug has since become a symbol for KEM’s nurses and medical practitioners across India, representing their aspirations and struggles for a safe and protected work environment. Following the brutal rape and murder of a young trainee doctor at RG Kar Medical College and Hospital in Kolkata, which sparked national outrage, Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud referenced Shanbaug’s case in his remarks on a suo motu petition addressing workplace safety for health professionals.

The 1973 case should have led to a nationwide protocol for the protection of medical practitioners, members of the fraternity said. However, 50 years later, there is no central protection law. The bill for the prevention of violence against healthcare professionals and clinical establishments is still pending approval in Parliament.

Shanbaug’s case prompted significant changes at KEM Hospital and the three BMC-run hospitals in Mumbai. Senior doctors and hospital administration implemented structural and security improvements, including increasing the number of security guards, tightening night-time security, and revising attendance rules.

At KEM, the 1,500 nurses, including 300 nursing students, now have a common changing room for female nurses, complete with lockers for their belongings. CCTV cameras monitor the premises, and access for relatives with patients is restricted, according to senior nurse Sunita Bhalerao (name changed).

Until her death in 2015, Shanbaug remained a living symbol for KEM’s nursing community and influenced the training experiences of young nurses. Nearly every nurse at KEM in the past 50 years cared for Shanbaug during her 45-year vegetative state.

When Bhalerao joined KEM as a student in 1991, the matron introduced her to Shanbaug, emphasising her connection to the nursing community. After Shanbaug’s death, Bhalerao, now a senior nurse, continued to remind trainee nurses of her case and its significance.

“Every nursing student is informed about Aruna's case. We tell them that such a case took place in the hospital. We don’t want to scare them, but to alert them about protecting themselves on duty in the hospital,” she says. “We inform them about the emergency bell, which they can ring discreetly in case of trouble, we give them contact details of the police, and there is a WhatsApp group as well with all the nurses.”

While Mumbai is relatively safe for women, incidents like the RG Kar Kolkata rape raise significant concerns among female medical professionals.

Pratik Dilip Debaje, the President of the Maharashtra State Association of Resident Doctors, expresses frustration over the lack of effective security measures at the state’s 29 medical colleges and public hospitals. “In the Kolkata case, the trainee doctor had no designated rest area and was forced to stay in a seminar room. Many of our colleges face similar issues, with some resting rooms cluttered with equipment and used as storage spaces,” he notes.

The most troubling issue remains ensuring the security of doctors and medical staff from angry relatives and excessive crowding in hospital premises. “Treating patients and managing relatives’ composure are two distinct responsibilities. We are trained for the former, not the latter. Often, relatives become violent and physically and verbally assault doctors,” he added.

Doctors and nurses emphasised that they have all faced enraged mobs and distressed relatives. Managing crowd flow in public hospitals continues to be a daunting challenge.

For example, KEM Hospital and GMC College covers a 42,000 sq meter area with multiple entry and exit gates. The 1,800-bed hospital alone sees a daily influx of 5,000 people, making it difficult for the 300 security guards to manage the crowd effectively around the clock.

Avinash Supe, the former dean of KEM, stated that the hospital has held several meetings to address security concerns. “We need to completely revamp the security system. KEM, built in 1925 by the British, was designed for the demands of that era. With the surge in footfall over the last century, we need improved crowd management. All patients, relatives, and staff on campus should be identified with ID cards. We must implement stricter security measures to ensure safety,” he said.

He noted that following Shanbaug’s case, there were numerous protests demanding better protection for medical staff. “Security measures are introduced, but their implementation weakens over time. It is only when incidents like the RG Kar hospital case or attacks on doctors occur that we again demand enhanced security,” he added.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(A shorter, edited version of this appeared in print as 'They Didn’t Cut the Tree')