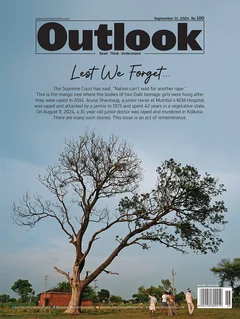

This is the cover story for Outlook's 11 September 2024 magazine issue 'Lest We Forget'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

Nineteen-year-old Angel* from Manipur is filled with terror every time she hears the revving of a car or spots one, especially if it’s a white four-by-four. She recalls how her attackers had come in white and purple Mahindra Bolero vehicles on May 15, 2023—a fortnight after ethnic clashes broke out between the Kukis and the Meiteis in Manipur—when she, a Kuki, was abducted from outside an ATM in East Imphal where she had gone to withdraw cash. Then 18, Angel was assaulted all night by mobs comprising Meitei men and women before being gang raped by unidentified armed men. She did not tell anyone about her ordeal till July, when inside a relief camp in Kangpokpi district where she and her family had taken shelter, Angel came across “that horrible video”. Her eyes welled up and a sharp pain seared her chest as she watched the video of the two women being assaulted and paraded naked by a mob. Though she did not know the women, she knew instantly what they had gone through. “I decided to fight for justice, not just for me but for all the women who faced this trauma,” she says.

Justice, however, remains elusive even after a year of national protests, international outrage, political mudslinging and interventions by the Supreme Court and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). None of Angel’s attackers has been arrested or even identified. She isn’t the only one. A majority of the survivors of sexual violence or kin of victims from the tribal Kuki-Zo communities, disproportionately targeted in the ethnic clashes, have so far received no relief or reassurance.

As the country is yet again devastated by the recent rape-murder of a young trainee doctor inside the R G Kar Medical College and Hospital in Kolkata, the women who faced sexual violence amid the conflict, and their kin, are once again confronted with the spectre of their memories and myriad questions: how long would they have to wait for justice? And how many women would have to be sacrificed for the system to wake up?

Angel says that her abductors were armed Meiteis who beat her with the butts of their guns and took her over to women in Wangkhei district who too beat her late into the night before handing her over to “men in black T-shirts, armed with knives, guns and ropes”. These men came in packs driving white Boleros; they blindfolded and tied her and drove her at gunpoint to Langol and then to Bishnupur while repeatedly assaulting her and threatening to kill her. They eventually decided to take her to a nearby hilltop past Ngariyan Ching (hill) where they took turns raping her. Having passed out after repeated beatings on her head, Angel requested permission to urinate upon waking up and her attackers untied her hands. “I knew I just had that one shot. If I did not escape, I would be killed on this hill. So I decided to make a run for it,” Angel recalls a year later. She somehow managed to roll down the hill where she was eventually rescued by a Meitei Pangal Muslim vegetable vendor who was driving by. He hid her amid his stash of vegetables and transported her to Bishnupur police station, even as her assailants followed with guns. Once they reached the station, Angel claims that she told the officers that she was being chased by armed men in cars who belonged to Arambai Tengol, a militant Meitei group that has been named in almost all cases of violence since last year. But when questioned, the mobs told the police that they were just members of a “club”.

“When the police let them go, I realised I wasn’t safe there, as the cops were also Meiteis,” she recalls. The Bishnupur Police has since denied any report of Angel being taken to the station. The Muslim driver helped the girl contact her family and eventually dropped her off in the care of some people from her community. On May 18, Kuki civil society organisations (CSOs) arranged for her to be driven to Kangpokpi and admitted to the district hospital from where she was referred to a hospital in Kohima, Nagaland. Scans of records from the hospital accessed by Outlook confirm “assault and rape on May 15, 2023, during the Manipur tribal clash”.

The teen now lives with her mother, father and elder brother in a rented flat in the middle of paddy fields enveloped by a ring of blue mountains. Having dropped out of school in class 8 due to health issues, Angel hopes to one day manage a small business to help out her mother, the only breadwinner in the house. For now, though, she remains in physical as well as mental pain. She has trouble eating solid food and gets intense migraines due to her severe head injuries. She does not like meeting anyone other than her family members and is often woken up by flashbacks when she goes to sleep.

About 100 km away, lack of anonymity due to the viral “naked parade” video has rendered the two Vaiphei community women isolated and deeply reclusive. With no homes left for them to return to, the two remain in Churachandpur with their families, trying to erase the memories of that day.

On May 4, a Meitei mob attacked B Phainom village where the women stayed, bordering East Imphal. The older survivor, in her 40s, is the wife of the village chief and related to the second survivor, who is 19 years old. After attacking the village, the mob began burning homes and beating the Kuki-Zo families. While the village chief managed to escape, his wife was left behind along with the 19-year-old and her father, brother and aunt. “The women along with some men ran and hid in a nearby bush. They would have escaped, had it not been for that miserable goat that got loose in the commotion and ran into the very bush behind which the group was hiding, leading the attackers to them,” says the village chief.

The incident has shaken them. “My wife does not talk much. She keeps to herself. We don’t bring up the incident at home,” the husband reiterates. He says that the children understand what happened but they too maintain silence. The mother of the 19-year-old, meanwhile, remains inconsolable. Her son and her husband, who were also hiding behind the bush, were killed by the mob while trying to protect the two women. “My daughter has to live with not just the memory of what happened to her, but also what happened to her brother and father. She watched them get killed,” she says.

Since the women are from the Vaiphei community, they are being protected by CSOs like the Zomi Council Steering Committee in Churachandpur who strictly supervise their care. “It becomes hard for them to deal with the memories that come flooding back every time they go online and see news about that video or reports about other brutal rape cases like the recent one in Kolkata. To protect them, we restrict their usage of social media,” a member of the Zillai (Vaiphei Students’ Organisation) related to the survivors says, adding that the community has ensured that the survivors receive proper medical care and mental health counselling.

“Fortunately or unfortunately, the video came out. It helped draw attention to the genocide that our people are facing, especially the atrocities against women,” says Kimneihoi Lhungdim, the general secretary of the Kuki Women Human Rights Organisation (KWHRO) in Lamka, the capital of Churachandpur district, which lies about 30 km from Meitei-dominated Bishnupur. A heavily militarised buffer zone and concertina wires divide the two areas, with the Kuki-Zo in the south-west of the state demanding a separate administration. “Separation is the only solution. It will also help us speed up the process of seeking justice for all the 203 Kuki-Zo victims who were killed in the violence, including 29 women,” says Haokip. “Thousands of women have also been displaced from their homes. They have lost their belongings, while hundreds have survived some form of abuse, violation or assault.”

At least 221 people have lost their lives since May 3 when violence erupted between the hill-dwelling Kuki-Zo tribes and the dominant Meitei community in Churachandpur over the Meitei’s demand to include the indigenous group in the Scheduled Tribes list. The conflict had been preceded by prolonged agitations by tribal groups against forest laws taking over tribal land and the persistent vilification and “otherisation” of the Kukis and illegal immigrants, militants, drug addicts or poppy cultivators.

The Kuki Inpi Manipur (KIM), the apex civil body of the Kukis, has been trying to provide relief and support to the thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) who remain in relief camps across Churachandpur and Kangpokpi. Through programmes like ‘Jangnadopna’ implemented by its subsidiary arms like the KWHRO, the organisation has provided an ex-gratia amount of Rs 1 lakh to the kin of some of the victims, including the brother and father of the 19-year-old survivor in Churachandpur. An orphanage being managed by the Kuki Women’s Union is currently providing a home to over 50 children who have lost both parents in the current conflict. The Kuki Students Organisation (KSO) and other bodies provide round-the-clock assistance and support to families and help maintain lines of communication. KIM President Ajang Khongsai says that while the community is doing all it can, the response of the courts, law enforcement agencies and the government has been less than adequate. “No compensation or rehabilitation schemes have yet been announced. Investigations in all the cases of violence and rioting have been slow and some haven’t even begun. Even in the cases of violence against women, the intervention of the Supreme Court came only on July 20, after the video went viral,” he says.

The Supreme Court took suo motu cognisance of the incident, and on August 7, transferred multiple cases, including the aforementioned cases and others to the CBI. It also set up Special Investigation Teams (SITs) to look into cases of violence and formed an all-women judicial panel to look into the nature of crimes against women in the conflict. In the order, a bench led by Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud, said, “In times of sectarian violence, mobs use sexual violence to send a message of subordination to the community that the victims or survivors hail from. Such visceral violence against women during conflict is nothing but an atrocity.”

After the initial uproar, investigations now seem to have hit the snooze button. While the CBI is reportedly investigating 27 cases of violence, including 19 cases of crimes against women, the affected families don’t have any updates. “The CBI spoke to me in October-November last year. Since then, we have not received any report from the CBI, the SIT, the Manipur Police or the Indian government,” says the father of Flora*, who was gang raped and murdered inside a car wash in Imphal East along with another Kuki girl—her friend and colleague Leena*. The father does not know if a chargesheet has been filed. The family also claims that a recorded phone conversation between a colleague of Flora and Leena’s roommate, in which the former intimated the latter of the alleged rape and murder of the two girls by Meitei gangs on May 4, was disregarded by the CBI when they informed the investigating officer about it. “We think they are trying to evade the rape charges,” says the father of the victim. The 56-year-old man and his wife have been displaced from their home and now live at a relative’s house in Kangpokpi. They listen to the recording on loop. They do not have anything to remember their daughter with, except for sketches of the eyebrows that she had been trying to master as part of her eyelash extension course. “She wanted to become a beautician,” Flora’s mother sighs, breaking down.

Angel and her family also do not know the status of her case and can barely afford her treatment. While a chargesheet has been filed in case of the Vaiphei women in Churachandpur, the trial has not yet started as the location of the trial has not yet been finalised. In March, the apex court had directed the Manipur government, the CBI and the National Investigation Agency (NIA) to file status reports on the investigation and chargesheets filed in cases of violence to decide whether the trials can commence in Assam or be shifted to Manipur.

This year in July, some civil society groups quietly observed 20 years since the brutal rape and killing of Thangjam Manorama and the significant anti-rape protests led by a group of 12 Manipuri mothers belonging to the Meira Paibi, a civil society organisation of elderly Meitei women. Manorama was arrested by the Assam Rifles from her home at night allegedly on suspicion of her involvement with an insurgent group. The next day, her bullet-riddled body was found at the base of Ngariyan Ching. In protest, 12 elderly women of the Meira Paibi walked to Imphal’s Kangla Fort, holding banners imploring “Indian Army Rape Us” and stripped. “We were helpless at the time, we didn’t know how else to stop the madness that was unfolding in Manipur,” says Ima Ngambi, one of the 12 Imas (mothers) who led the nude protest. The rape and murder of Manorama, now infamous as one of the worst alleged cases of “fake encounters” recorded in India, remains unsolved, meaning that the fight was not yet over. “Our fight is not just for Manorama, but for all women, like the doctor raped in Kolkata, or even the women paraded naked in the viral video last year. That should not have happened,” says Ngambi, who is president of the Apunba Manipur Kanba Ima Lup. Yet, the Meira Paibi have been named by all the complainants mentioned above as the perpetrators of violence and facilitators of sexual violence against them, bringing their role as bearers of the torch for women’s empowerment under scrutiny.

“It was the Meira Paibi women who told us that we would be raped and killed because of rumours that Kukis were raping Meitei women in Churachandpur. The women, known for being peacekeepers for centuries, turned into perpetrators of violence,” recalls Chin Sian Chiang, a former nursing student in Imphal who was dragged out of her college hostel along with another Kuki girl by a mob on May 4 last year, beaten and paraded down a road. Chiang realises with sadness that she escaped the fate that many of her fellow-survivors could not. The 23-year-old, who is currently recovering from her injuries in Churachandpur after receiving treatment at AIIMS last year, says that she is grateful to be alive. “It feels horrible to say this, but I think I got lucky,” she says.

(*Names have been changed to protect identity)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Rakhi Bose in Churachandpur, Kangpokpi and Imphal

(This appeared in the print as 'Criminal Amnesia')