Summary of this article

Kabul falls overnight, leaving the writers shocked, sleepless, and struggling to process the sudden loss of the city.

Schools, universities, and offices shut abruptly as fear spreads and daily life collapses within hours.

People hurriedly flee hostels and workplaces with minimal belongings, facing deep uncertainty about their futures

Kabul fell to Taliban control on 15 August 2021 —the writers were in touch through the night that followed. All of the writers in this section were writing from the city of Kabul. This is their collective diary: in it, they watch schools and offices close, families change and freedoms disappear. They share stories of chaos, protest and flight—and of life continuing.

Maryam

I don’t have any sleep. It is night-time, and Kabul has fallen fully. I cannot believe it. I want to tell everyone: they took Kabul. I want to tell my mother, my sisters, my brothers—they have taken Kabul. I want to go up to the roof and say quietly – they took Kabul. I don’t know why I can’t just shout it out: THEY TOOK KABUL.

Through the night and into the next morning the writers reflect on what has happened and recount the day they have just lived through.

Fakhta

Fakhta lives in a university hostel in the capital, and is close to getting her degree in Law from Kabul University. Her home is in the mountainous province of Daikundi.

I woke up when my phone rang. My mother gave me the news. She said our whole province—including our district, Nili, at the centre of Daikundi—is in the hands of the Taliban. She was upset. She said, ‘I wish you had not gone back to the university in Kabul.’

She was right. Apart from Kabul, all other cities are already in the hands of the Taliban. They now control all the highways. The only thing left to happen was for the Taliban to enter the capital and take over the presidential palace. I said goodbye to my mother and lay back on my bed in the hostel, looking out of the window, shocked and anxious.

I got up and went to class. I was late and slipped into the lecture. After about twenty minutes, everyone’s phone began to ring; the lecturer’s too.

Sadaf

Sadaf is a teacher. She is teaching a class of girls in Year 8, most of whom would be fourteen or fifteen years old.

I distributed the exam papers and gave my students their instructions. At 11 a.m. I explained the instructions to them and wrote a few more on the blackboard with white chalk. The students asked questions and I answered them. The class was so calm, like the silence before a storm. Then the door opened, and the head teacher came in. She started collecting the exam papers although we hadn’t even started. Her hands were shaking, and she asked me to help her. I saw my students’ faces, pale with fear. We told them to go home.

Parand

I was at the office, as usual. I had only just started working when the office phone rang. We were told that the situation was getting worse, that the Taliban had entered the city and we should leave the office. I was not afraid: it was not news. We knew the Taliban would be coming back and I witnessed the same turmoil twenty-five years ago. But I had no choice but to leave alongside two of my colleagues, who were younger and so afraid you could see their skin turn pale.

Fakhta

As I walked quickly back to the university hostel, I worried about my fiancé. He is in the army in Uruzgan Province. He is someone who has fought the Taliban face to face. If he is recognised by any of them, I will have to say goodbye forever. I knew he was in Kabul for a few days, on leave, and all the way back to the hostel I kept trying to reach him on my phone. I must have called twenty times. But I never got to hear his voice.

Hurrying my steps, I ran into the hostel grounds. As I entered the corridor, everyone was leaving, some with luggage, some with belongings stuffed into plastic bags. In my room, I saw Mitra gathering her things. Without saying Salam, she told me to collect my stuff and leave the hostel as soon as possible. ‘The teachers said, it is only for a few days. When the situation gets better, we can come back.’ I said goodbye to Mitra and picked up a plastic bag. I put in a few clothes and Kafka on The Shore. I was reaching for my ID card and other documents which I keep at the back of my bookshelf when the teacher in charge shouted at me to leave so she could close the hostel.

Najla

Najla works as an office manager but is not at work on 15 August.

We needed money at home. The way to the bank was long; I had to pass through the market. Men and women were busy shopping for their daily groceries. For a moment, I felt happy that life was going on. I saw a few people I pass daily, who used to shave their beards and now have left them to grow. I saw high-school girls. I enjoyed looking at them in their black uniforms with white headscarves. I asked myself if I would see this sight again. When I arrived at the bank, there was such a huge crowd I thought there must be a protest. People were shouting and swearing at the bank staff. Police were trying to bring some order to the crowd.

Sadaf

It was crowded in the streets. No one could pass through, neither pedestrians nor cyclists. Everyone was in shock and panicking. The roads were blocked. I decided to take the longer route home, around the back of the mountain. At this moment, I saw my brother coming in his car to pick me up and drop me home safely. I was scared, but not as scared as we were before Karzai’s government. I also lived five years in such chaos. Maybe we are used to it. The only thing that upsets me is this: as a child I grew up in wartime, as a young girl I saw war; when will I be able to live?

Fakhta

Everyone was running towards the main road. I joined a couple of girls heading in that direction. Around me, I could only see girls with luggage trying to hail taxis. Because of the demand, taxis charged three or four times the usual amount.

One of the girls asked me where I wanted to go. The question hit me hard. I didn’t know. My only place in Kabul was the hostel. I have some distant relatives in Kabul who are poor, and I didn’t want to be a burden on them. I tried calling my fiancé again. Maybe he had relatives I could go to in Kabul. But I couldn’t reach him though I tried five or six times. A vehicle came, heading for Barchi. The girls with me wanted to go to Barchi. Afraid of being left alone, I said I would also go to Barchi. All the way, I kept trying to reach my fiancé, but I could not speak to him.

Parand

The driver sped through the streets. We were lucky not to see any of the Taliban, but the panic around us was overwhelming. Everyone was running in different directions. We were also driven in an unknown direction through the crowd. Finally, we found ourselves in Char-rahi Baraki.

Next to our office car was a taxi, also trying to get somewhere. A man leaned out of it and said to our driver, ‘Brother, leave the car and save yourself. I left my office car in the middle of the road and took this taxi.’ At the same time, our driver got a call advising him to leave us on the road and return the car to the office. I was shocked to see this sudden change in men. For them, the car was more valuable than three women’s lives in the midst of this horror.

Najla

I was scared. I abandoned my trip to the bank and started back for home. I had to pass through the market again – now women were even running away. In a blink of an eye, the shopkeepers closed their shops. I heard that the Taliban had crossed Pul-e-charkhi prison in Kabul and were coming into the city. It was said they had entered the city from all possible sides, broken the prison doors and set all prisoners free. A few men passed on motorbikes, with long unkempt hair and guns in hand. The things I usually saw on TV, I now saw in front of me. There was gunfire and I thought war had started. Suddenly, I saw many aeroplanes in the sky.

Marie

Marie is approaching her thirtieth birthday, working in the marketing department of a German NGO in Kabul and heading her own organisation, a women-led counselling service, in her spare time. She lives with her parents and siblings.

We were told to work from home. I collected my laptop charger from the office and quickly took the road to Ansari roundabout. The roundabout was unbearably crowded. I saw people rushing, trying to get somewhere, all tangled up in each other. Every person looked unhappy: they swore if their way was blocked. There were no traffic police. It was not normal at all.

After a lot of trouble, I found a taxi with four women and a man. The man sat in the front seat. He said to the taxi driver, ‘Hurry up, please, the Taliban has reached Shahrak Ettefaq.’ I asked, ‘Where is Shahrak Ettefaq?’ He answered, ‘Dasht-e-Barchi.’ It was not just me: the other three women also froze in their seats.

Parand

We had to walk amid the moving crowd. There were a few men who laughed at us, saying, At last your good times are gone; now you women will have to stay inside. A few were enjoying themselves so much they hurled abuse at us – in words, and then physically. We walked for two hours before I saw a member of my family – my eyes welled up at the sight of them. Since then, I’ve been wondering, is it just the

Taliban or all men in this country who are against women’s freedom?

Najla

Back at home, I listened to the news: the Taliban had taken over Kabul, and Ashraf Ghani left the country with his staff. The Taliban were in the presidential palace.

What will happen tomorrow?

Marie

After two hours of driving, finally, I could see the yellow Silo building behind the trees. I had to walk the rest of the way home. I was very close to Kot-e-Sangi when I heard people rushing, calling to each other that the Taliban had reached District 5. I imagined the Taliban with their whips in hand, running after people and beating us to our death. The way I was dressed could be dangerous: they would shoot me right away, I thought. I started running too. My throat was dry and burning with fear. My feet started to give up on me, I kept losing my balance.

Yesterday’s city had disappeared. The shops were closed. The men with their fruit and vegetable carts were gone. Kot-e-Sangi, which could always contain human after human, had emptied out completely. Even the sun did not feel like yesterday. Everywhere felt dark and full of fright.

It was as though the people of this city had died before the Taliban entered Kabul. These dead people were now carrying their bodies in search of a graveyard in which to rest. On Sunday, 15 August 2021, the city of Kabul and its people turned into a Miyazaki animation.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

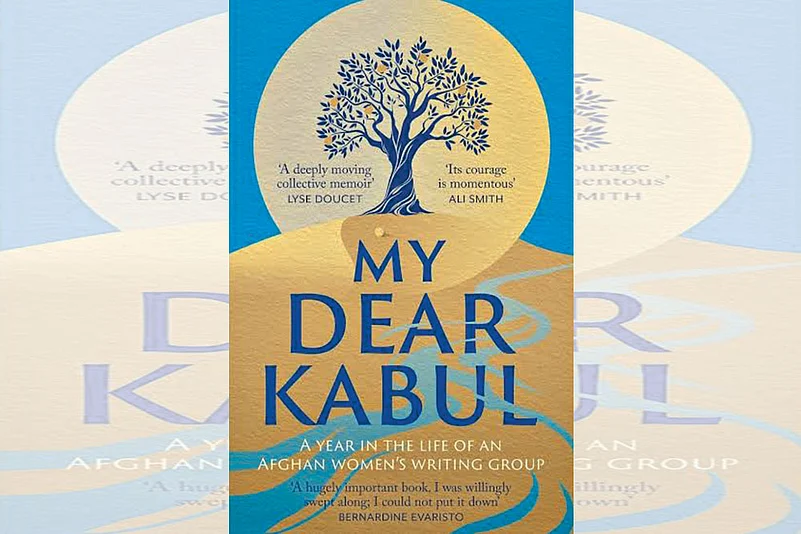

My Dear Kabul: A Year in the Life of an Afghan Women’s Writing Group published by Coronet/Hodder, 2024. Translated by Parwana Fayyaz and Dr Negeen Kargar.

My Dear Kabul is an Untold Narratives project. Untold—a development programme for emerging writers in areas of conflict and post-conflict—was founded by Lucy Hannah

The author will be at the Exide Kolkata Literary Meet from January 22-26