Summary of this article

Golwalkar, the second sarsanghachalak (or chief) of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), was possibly the most complicated and contradictory figure of modern India.

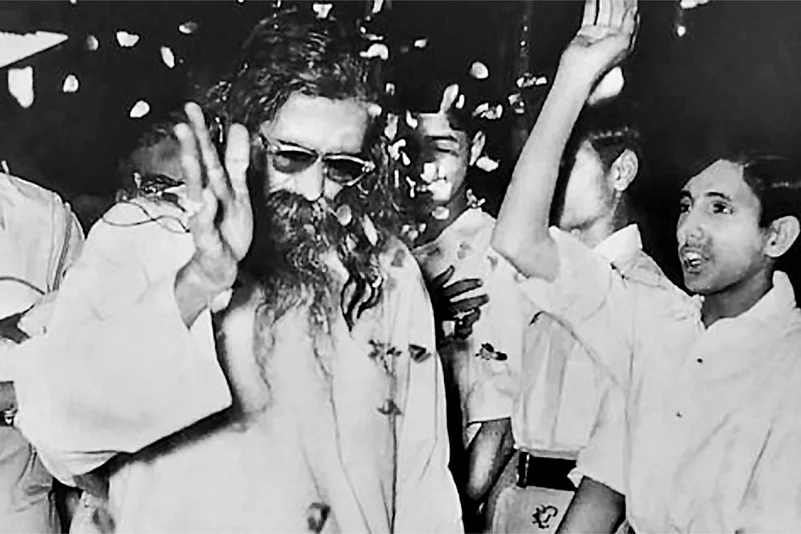

Golwalkar, or ‘Guruji’, took over as the RSS chief after the death of Hedgewar in 1940.

His growing hatred for a multi-religious nation made him hostile to the idea of secular democracy.

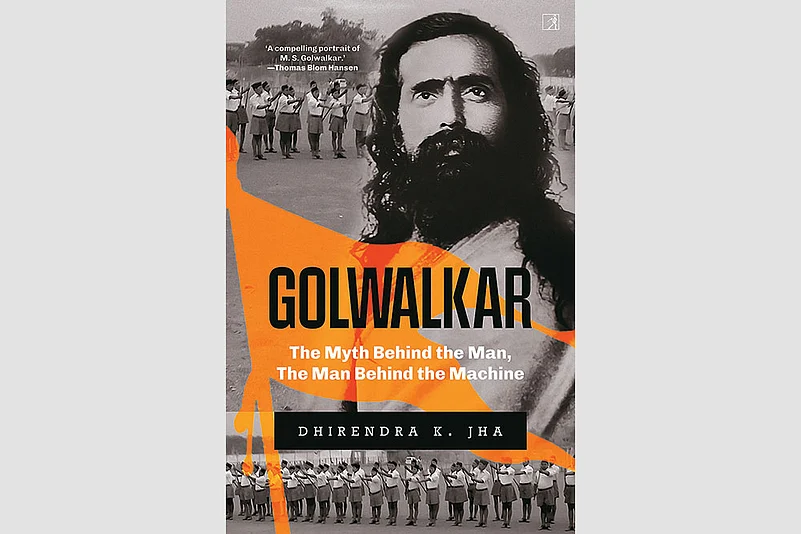

Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, the second sarsanghachalak (or chief) of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), was possibly the most complicated and contradictory figure of modern India. Inside the RSS, he is regarded as an ascetic figure—a demi-god of Hindutva politics—and is often accorded a status higher than even the founder of the organisation, K.B. Hedgewar. Outside, he is considered the biggest communal instigator, an icon of true evil who wanted to destroy India’s plural ethos and secularism.

Golwalkar, or ‘Guruji’, took over as the RSS chief after the death of Hedgewar in 1940 and remained its sarsanghachalak till his own death in 1973. When he assumed charge, the RSS lacked any major presence outside the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. Under him, the organisation passed through many ups and downs but kept growing all the while. It played an incendiary role in the Partition violence and was banned after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. By the time Golwalkar died, the RSS had extended across the entire country, and its network of allied organisations—the Sangh Parivar—had penetrated almost every aspect of Indian society. His ideological influence did not end with his death: his books—We or Our Nationhood Defined (1939) and Bunch of Thoughts (1966)—provided the core of the Sangh’s credo.

Though indirectly, Savarkar was the first to defend the Nazi’s treatment of jews in the Third Reich. Golwalkar, with his own keen sense for the effectiveness of primitive emotions, quickly went ahead of the Hindutva ideologue by pushing this line of thinking to extremes. In We or our Nationhood Defined, Golwalkar attempted to deal with his repugnance for Muslims and took Hindutva’s prevalent attraction for European dictatorships to a new level. The virulent idea fuelling the RSS—which demanded that Hindus must be granted the exclusive right to define India’s national identity—was in nebulous form in Savarkar’s treatise on Hindutva. His speeches in support of European dictators and their policies, too, were largely guarded. Golwalkar argued his views sharply and consistently and added considerable details to the idea of Hindutva. Without any ambiguity, he presented the Nazi treatment of Jews as a model to be applied on Indian minorities, especially Muslims, and thus provided the core of the Sangh’s credo.

‘To keep up the purity of the Race and its culture, Germany shocked the world by her purging the country of the semitic Races—the Jews,’ Golwalkar wrote. ‘Race pride at its highest has been manifested here. Germany has also shown how well nigh impossible it is for Races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united whole, a good lesson for us in Hindusthan to learn and profit by’. 11

With Nazi experiment of cleansing of Jews in mind, Golwalkar—having declared Muslims and Christians as foreign races— prescribed a formula for India:

From this standpoint, sanctioned by the experience of shrewd old nations, the foreign races in Hindusthan must either adopt the Hindu culture and language, must learn to respect and hold in reverence Hindu religion, must entertain no idea but those of the glorification of the Hindu race and culture, i.e., of the Hindu nation and must lose their separate existence to merge in the Hindu race, or may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu Nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment—not even citizen’s right. There is, at least should be, no other course for them to adopt. We are an old nation; let us deal as old nations ought to and do deal, with the foreign races, who have chosen to live in our country. 12

Evidently, German theoreticians, especially Swiss jurist Johann Kaspar Bluntschli, had made a deep impression on him. In the book, he made continuous references to them—though he misspelled Bluntschli as ‘Blunstley’—as he set out to radically reject the idea of India being a multi-religious nation. ‘Most of the books mentioned by Golwalkar are illustrative of the German ethnic definition of nationalism,’ writes French political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot. ‘He paid little attention to the English authors from whom the Congress leaders drew their idea of the nation in universalistic terms, such as the role of individual will and the social contract.’ 13

Golwalkar’s growing hatred for a multi-religious nation made him hostile to the idea of secular democracy. He despised the word ‘Indian’ and called it ‘the outlandish name’ which was coined to strengthen ‘wrong notions of democracy’ by promoting unity among people of different religions, particularly Hindus and Muslims. ‘The result of this poison is too well known,’ he wrote. ‘We have allowed ourselves to be duped into believing our foes to be our friends and with our own hands are undermining true nationality. That is the real danger of the day, our self-forgetfulness, our believing our old and bitter enemies to be our friends.’ 14

In We or Our Nationhood Defined, Golwalkar sought to bring communal cruelty to the history of India as an inescapable part of nation-building. He imagined a long period of ‘unflinching war’ through which the ‘Hindu nation’ struggled for existence and protection of its ‘swa’ or identity. ‘Ever since that evil day, when Moslems first landed in Hindusthan, right up to the present moment, the Hindu Nation has been gallantly fighting on to shake off the despoliers,’ he wrote. ‘It is the fortune of war, the tide turns now to this side, now to that, but the war goes on and has not been decided yet. Nor is there any fear of its being decided to our detriment. The Race Spirit has been awakening.’ 15

Concluding what he called ‘the History of Hindusthan’, he sought to carry Hindus into a state of constant opposition toward Muslims:

In short our history is the story of our flourishing Hindu National life for thousands of years and then of a long unflinching war continuing for the last ten centuries, which has not yet come to a decisive close. And when we understand our history, thus rightly, we find ourselves not the degenerate, downtrodden, uncivilised slaves that we are taught to believe we are today, but a nation, a free nation of illustrious heroes fighting the forces of destruction for the last thousand years and determined to carry on the struggle to the bitter end with ever-increasing zeal and unflagging national ardour. And Race Spirit calls. National consciousness blazes forth and we Hindus rally to the Hindu Standard, the Bhagawa Dhwaja, set our teeth in grim determination to wipe out the opposing forces.16

Nevertheless, the component of the communal theory of history in Golwalkar’s thought cannot be attributed solely to him. He was really reflecting the imagination of India’s past as presented by Savarkar. In Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?, Savarkar had written that a ‘conflict of life and death’ ensued ‘after Mohammad of Gazni crossed the Indus’ and invaded India: ‘In this prolonged furious conflict our people became intensely conscious of ourselves as Hindus and were welded into a nation to an extent unknown in our history.’ 17

Golwalkar carried Savarkarite imagination of India’s past further. He took the idea, developed it, turned it into an actionable programme and made it part of a blueprint meant to achieve their common goal—the Hindu Rashtra.

Dhirendra K. Jha is a senior political journalist. He is the author of several books, including Golwalkar, Shadow Armies, Gandhi’s Assassin and the co-author of Ayodhya: The Dark Night

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared in Outlook Magazine's 21 October Edition 'Who Is An Indian?' as One Hundred Years Of...Creating Heroes.