Long-standing warnings about the Himalayan region’s vulnerability have been ignored.

Recent landslides and floods in J&K were compounded by deforestation.

The most affected areas are in the geologically fragile Pir Panjal, Shivalik ranges.

In June 1992, as a schoolkid, I attended an environmental summer camp in the picturesque Himalayan town, Batote, located midway on the Jammu-Srinagar National Highway 1A. The camp was designed to sensitise young people to the fragile ecosystems of the Himalayan states in northern India. Organised jointly by the Institute of Jammu & Kashmir Affairs and the Jammu and Kashmir Environment Department, it brought together students aged 10 to 14 years.

The summer camp opened our eyes to the broader challenges the Himalayas face, with debates and symposiums held in Urdu and English on the issue. One memory that remains etched more than three decades later is a lecture by the highly respected late P Patnaik, a retired Principal Chief Conservator of Forests. He cautioned us that the Shivalik Hills, of the lower Himalayas, were among the youngest and most vulnerable stretches of the Himalayas. He underscored the need for rigorous scrutiny of future infrastructure projects in the region.

For that week, children from the upper reaches of the region engaged passionately in discussions on the many dimensions of the environment.

Today, as I witness natural tragedies, including the recent fatalities in Kishtwar and at Vaishno Devi, in the very region where I spent my formative years in the foothills of the Himalayas, the lessons of that summer camp begin to echo. Over the past three decades, there has been a multi-dimensional failure across the region. The immediate trigger for many of these landslides seems to be intense rainfall, but the underlying cause is unchecked deforestation and the loss of natural vegetation. Without deeply rooted trees and shrubs that can anchor the soil, fragile slopes crumble easily, turning downpours into deadly landslides.

More than 150 people have reportedly been killed in the recent floods across Jammu and Kashmir, with the heaviest toll reported from the Pir Panjal and Shivalik ranges. They are two of the most geologically fragile stretches of the Himalayan system. The Shivalik range, which forms the outermost foothills of the Himalayas, runs through Jammu, Punjab and parts of Himachal Pradesh, while the Pir Panjal forms a formidable mountain wall, separating the Kashmir Valley from the rest of the Indian subcontinent, stretching from the Kishtwar-Himachal border in the east, across Poonch and Rajouri to Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-administered Jammu and Kashmir, where it merges with the Hazara-Kaghan ranges near the western Himalayas.

Kishtwar district, located in the Pir Panjal, accounted for nearly 100 of the recent deaths, including 66 Machail Mata temple pilgrims, whose bodies were recovered at Chashotí after a cloudburst triggered a landslide on August 14. Thirty-one people are still missing, feared dead. Less than two weeks later, another 34 devotees on their way to the Vaishno Devi shrine lost their lives in a landslide at Adh-Kunwari, located in the Shivalik hills that dominate the southern parts of Jammu and Kashmir.

In the same Himalayan system, seven fatalities each were reported from Kathua, located in the Shivaliks and the adjoining plains, and from Reasi, straddling the Shivalik-Pir Panjal transition zone. And there were four deaths each recorded at Doda and Ramban, both located in the Pir Panjal range. This is apart from further casualties reported in other districts.

The pattern of destruction underscores a critical geographical reality: the Shivalik and Pir Panjal ranges, integral to the Himalayan system, are far more unstable than the Greater Himalayas to the north. The Shivaliks, the youngest part of the Himalayas, are made up of loose sediments that crumble easily during heavy rains, while the Pir Panjal, part of the Lesser Himalayas, is prone to landslides and flash floods due to its fractured geology and steep slopes.

The twin tragedies at Kishtwar in the Pir Panjal and at Vaishno Devi in the Shivalik illustrate how pilgrimage routes and settlements in these vulnerable zones are at particular risk when extreme weather events are becoming more frequent.

By contrast, the Greater Himalayas (Himadri) are geologically older and structurally more consolidated. Rising as some of the highest peaks on Earth, they form a massive natural boundary between the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan plateau of China. This towering wall not only acts as a geopolitical frontier but also plays a critical climatic role: it blocks the southwesterly monsoon winds, forcing them to shed their moisture over the subcontinent, which sustains the monsoon-dependent agriculture and ecosystems across South Asia.

What is unfolding here is not an isolated regional tragedy but part of a much larger global story. The Himalayas, often called the “Third Pole” for their vast reserves of ice and freshwater, are among the most climate-sensitive regions on the planet. Rising temperatures, erratic rainfall and glacial retreat, driven by global warming, are colliding with unrestrained development to intensify disasters. The human cost in the Himalayas is therefore both a local and global warning: in an era of accelerating climate change, neglecting ecological foresight for short-term development carries consequences that reverberate far beyond national boundaries. To grasp the scale of the crisis, it is essential to unpack its many vectors, rather than reduce the challenge to broad generalities.

To begin, Vaishno Devi, which welcomes nearly ten million pilgrims annually, has become especially vulnerable, with more than three dozen fatalities reported in a recent landslide. Those of us who remember this pilgrimage from the 1980s will recall how arduous the journey to the shrine was, without e-rickshaws or helicopters, when the number of pilgrims was far smaller.

The Jammu and Kashmir government constituted the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board under a 1988 Act to provide better management, administration and governance of the shrine and its endowments, including its lands and buildings, from Katra up to the holy cave and the adjoining hillocks. Over the next two decades, the shrine became one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in the country. This surge brought immense prosperity to Katra and its hoteliers. The growth was so rapid that by the late 1990s, security concerns had become real for some. I witnessed a teenage classmate arrive at a tuition center in a car accompanied by bodyguards due to threats to his life, a side effect of the region's burgeoning prosperity.

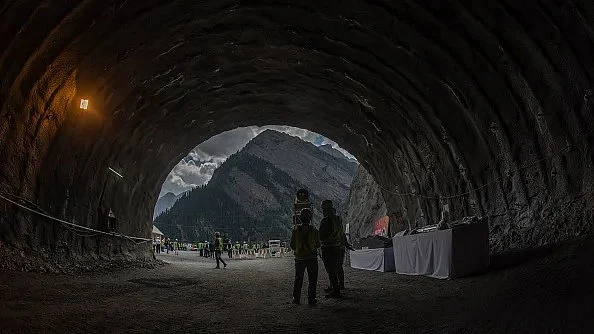

The expansion of the Vaishno Devi pilgrimage was sudden and massive. Mountains were carved to shorten the pathways and, even now, there are plans underway for a gondola. The shrine board’s mandate includes overseeing its administration, governance and maintenance, the pilgrimage route itself, and the surrounding lands. It comprises a diverse set of members, including the Lieutenant Governor of Jammu and Kashmir (ex-officio Chairman), spiritual leaders, philanthropists, former bureaucrats and professionals from various fields. Yet it notably lacks specialists in ecology, environmental science or geology. The absence of such technical expertise is concerning given the ecological sensitivity of the Trikuta Hills.

The response in India to many such tragedies remains largely reactive. After the recent devastating floods, Union Home Minister Amit Shah visited Jammu and Kashmir to assess the damage and oversee relief operations. He announced that the Central government had allocated ₹209 crore as its share to the State Disaster Response Fund, acknowledging the region’s vulnerability to natural disasters. Yet, such measures are mere band-aids for problems that will inevitably recur, often with greater ferocity.

The tragedy, therefore, is not limited to the visible human toll of landslides and floods. It lies in our collective failure, across governments, institutions, civil society and citizens, to weave ecological foresight into development.

Growing up, we heard of Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Sundar Bahuguna's pioneering work in the Himalayas. At present, there is absence of civil society action that could create societal awareness of the challenges. In the 1990s, I attended a series of environmental camps in the region, guided by upright forest officers such as late Sardar Sohan Singh, the Chief Conservator of Jammu and Kashmir renowned for his honesty, who worked tirelessly to instill the importance of ecological balance in the younger generation. Today, however, awareness of the environmental challenges facing the region is minimal.

Where forests were once exploited through collusion between capitalist interests and pliant officials, today it is large-scale infrastructure projects that bulldoze mountains with little regard for ecological consequences that do this job. While achievements such as the railway to the Kashmir Valley and new roadways across the Himalayan states are celebrated, their environmental costs are too often ignored. The consequences are plain to see, as recurring landslides regularly block National Highway 1A and this season of unprecedented rains has only aggravated the challenge.

Natural exit points for rivers have been blocked, exacerbating the impact of seasonal rains. Meanwhile, in the upper reaches of the Himalayas and Ladakh, glaciers are melting at an alarming rate, further increasing water flow and compounding the effects of global warming. The melting glaciers not only threaten local communities through floods and landslides but also disrupt river systems that millions downstream depend on for agriculture, drinking water and electricity.

Moreover, increased deforestation, unchecked construction and poorly planned tourism in fragile areas have triggered soil erosion, degraded forests, and destabilised mountain slopes across the region.

The wisdom of earlier visionaries such as Patnaik, Bhatt and Bahuguna, and of dedicated forest officers like Sardar Sohan Singh, is more urgently required today than ever before. The continued neglect of environmental safeguards could accelerate glacial melt, intensify river flooding and trigger more ecological collapse in sensitive zones. Yet the Himalayas continue to bear the cost of short-term gains, patronage-driven decision-making and a lack of environmental consciousness. This is a classic reminder that we must return to basics: the reckless tampering with nature must end.