In December last year, when BJP assumed power in Chhattisgarh and Vishnu Deo Singh became the first-ever tribal chief minister of the state, the biodiversity-rich Hasdeo Arand region once again began witnessing widespread deforestation. Fuelled further by the recent Forest (Conservation) Act, 2023, (FCA) the movement to protect the forest lands in the state’s tribal-dominated Surguja district is resurfacing as a key political flashpoint ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections. Activists believe that the Act, which overrules the significant Forest Rights Act, of 2006, will have an even more adverse impact on Hasdeo.

In the last weeks of December and early this year, thousands of trees have been felled in a bid to clear massive swathes of land for the Parsa East and Kete Basan (PEKB) phase-2 extension coal mines in the Hasdeo region. Deforestation has been carried out under tight security with the police allegedly detaining local Adivasi leaders and activists, who have tried to halt mining projects undertaken by Adani Enterprises Ltd in this region since 2011 when industrialist Gautam Adani received forest clearance to carry out mining in the PEKB by then environment and forest minister Jairam Ramesh.

Over the years, the Hasdeo forest protests against the mining at PEKB have become a rallying point for environmentalists trying to protect forest lands from turning into mines or other industrial units. Much of the objection has been centered around the changes to the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, introduced in 2022, which make the process for governments and developers to acquire lands for mining and business purposes much easier, without consideration for local stakeholders.

Forest rights activists and advocates point out that the new rules will dilute the provisions meant to safeguard the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 or Forest Rights Act, (FRA), 2006, which gave forest dwelling communities agency to decide what they wanted to do with the land they inhabited and around which their lives revolved.

How has the FRA been diluted over the years?

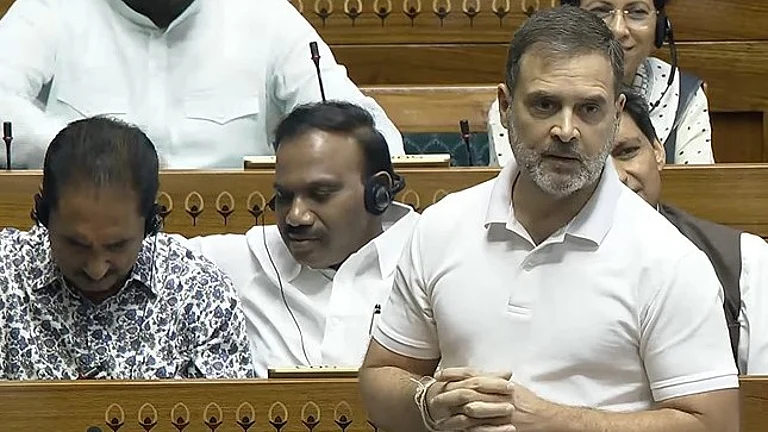

Despite wide criticisms by activists and NGOs that carried out nationwide protests, the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha by Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav on March 27, 2022.

In the last week of July 2022, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) notified the contentious ‘Forest (Conservation) Rules 2022’ that brought about a set of amendments to the FCA, which was enacted for the conservation of forests across the country in several ways including restricting the use of forests for non-forest purposes including mining, tourism etc.

It was cleared by Lok Sabha on July 26 and by the Rajya Sabha on August 2. The Bill received the Presidential assent shortly thereafter (August 4).

The principal thrust of the modifications to FRA is the redefinition of what a ‘forest’ is, as per Indian law. The new Act stipulates that it will apply only to those lands that were notified as ‘forest’ under the Indian Forest Act 1927, any other relevant law or those that have been officially recorded as a forest on or after October 25, 1980. However, under the new amendments, the definition of forests applies to “notified forests” only.

What is a forest?

Amid a long-standing debate about the lack of a legal definition of a forest in Indian law, the 1996 Godavarman judgment of the Supreme Court gives a somewhat comprehensive definition of a forest: the word ‘forest’ must be understood according to its dictionary meaning.

According to the judgment, ‘This description covers all statutorily recognised forests, whether designated as reserved, protected or otherwise for the purpose of Section 2(i) of the Forest Conservation Act (1980). The term forest land, occurring in Section 2, will not only include forest as understood in the dictionary sense but also any area recorded as forest in the government record irrespective of the ownership.'

“With the new forest Act, the BJP government has gone diabolically against the Godavarman judgment along with two other judgments of 1997 and 2013, all of which collectively remain crucial to India’s forest rights movements,” says advocate Colin Gonsalves, a senior Supreme Court advocate and the founder of Human Rights Law Network.

In 1997, through the Samata Judgement of 1997 (Samata vs. State of Andhra Pradesh), the court upheld that no private party can do mining in a Scheduled Area. Similarly, the Niyamgiri Judgment of 2013, (Odisha Mining Corporation vs Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change), upheld that under the FRA, allotments of lands to the tribals have to be completed first before any public project is considered, and the third is, the Godavarman judgment (Godavarman Thirumulkpad v. Union of India & Ors), which stated that “forests” means all forests naturally found and not limited to notified forests.

With the amendments, the Central government is trying to overrule all these three judgments, says Gonsalves, adding, “Imagine, with the amended FCA, that restricts the definition of forests to only notified forests, about 50 per cent to 75 per cent of the country’s forest areas will cease to be forests. I cannot fathom the amount of environmental degradation that will result from it. This will now open these areas, inhabited by dense tribal population, to mining, tourism, non-forest activities, and commercial exploitation.”

Thus, diluting the FRA also dilutes the power of the Gram Sabhas and the rights of tribals.

Gram Sabha(s) lose power

The new Rule makes no mention of the consent of the Gram Sabha before clearance is given to corporates -- a consequential change --- which was made mandatory in the FCA in 2017 through an amendment. The FRA also mandated that informed consent be taken from the Gram Sabha before the diversion of forest land.

Quoting a legal researcher, Down to Earth, a publication reporting on the environment and climate, noted that seeking consent from the Gram Sabha was a legal standard that the ministry itself had first upheld through a circular in 2009 and in the Rules under the FCA in 2017. “It had thus democratised the forest diversion procedure that has historically been opaque and exclusionary,” the report said.

Speaking to the media, Alok Shukla, the convenor of Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan said that under immense pressure from Adani to conduct mining across PEKB, a series of fake Gram Sabhas have been conducted by the district administration for seven coal blocks allotted to the corporate.

Diminishing tribal rights

Gonsalves explains that all tribals and non-tribals have rights to lands and a patta under the FRA. “Tribal residents, residing in a forest area for several years, can apply for a permanent patta under this Act. In correspondence to the block they have been staying in and using it for their cultivation purpose, they get ownership of the land --- a title --- from the state governments. For non-tribal dwellers, they have to show a 30-year residential proof to receive the same.”

Now, with the definition of forest being changed, depending on whether the state governments choose to notify a certain forested area as “forests”, hundreds of tribal communities would lose their right to land ownership.

In September 2022, Outlook attended a press conference where several environment activists, who have been fighting Vedanta’s bauxite mining in Mali Parbat, explained how under the new Rules, the government can enter into a contract with the big corporates first and then leave it on the State governments to deal with the land rights conflicts of the tribals.

Pointing out the fallacy of putting the State governments in charge of ensuring individual and community tribal rights through the new Rule, Gonsalves says, “What is the use of such an exercise if the land has already been handed over to the corporate houses? Such amendments will effectively do away with the most important statute of the tribals, the FRA.”

Such a situation will create a “fait accompli” which will force the tribals of their lands even before the settlement of their claims is finalized.

Dispute over land claim

Much before the amendments were brought in, several cases over claims of lands by forest dwellers had been pending before the Supreme Court. As per data released in a press release, 80 percent of these claims have been rejected by the Centre in recent years.

According to a report by The Wire, the average rate of rejection has been 54 per cent since 2008, with a total of 3.8 million claims made since the implementation of FRA in the same year. Between May 2015 and April 2016, however, the average rose to 79 per cent, for 2.7 lakh claims.

A government press release, dated 14.03.2016, justified the rejections on the grounds of lack of evidence. “The major reasons for rejection of claims that have come to the notice of this Ministry are non-occupation of forest land as of 13.12.2005, claims being made on land other than forest land/revenue land, multiple claims and lack of evidence of residing on the forest land for the specified period of time (this is particularly in the case of Other Traditional Forest Dwellers)".

Speaking at the press conference, a representative of the Mulniwasi Samajsevak Sangh, a socio-culture organisation fighting for tribal rights, said, “A perusal of the so-called rejection orders show that they are one line or cryptic orders without reasons and therefore illegal and the appeals against these orders are yet to be filed.”

Ahead of the 2024 elections, what does this mean?

Whether PEKB in Chhattisgarh or Mali Parbat in Odisha, such mining exercises are being pushed through more and more in the run-up to the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. “After the Central government finalizes the deals with the corporate houses, it will only bolster the funding BJP requires ahead of the general elections,” says Gonsalves.

In July 2022, over 100 former civil servants wrote to the Parliament expressing their concerns over “the content of the Bill as well as the procedure by which the Bill is being examined and passed”. The constitutional validity of the amendments has also been heavily questioned and criticised for diminishing the rights of millions of tribals who are being forced to part with their legally owned land and give them to corporate houses for mining and non-forest activities.