Summary of this article

The U.S. raid signals a shift in global politics where coercion is increasingly normalised and sovereignty appears conditional on power rather than protected by law.

From Ukraine to Taiwan, major powers are more willing to use force with limited consequences, while the UN functions less as a constraint and more as a forum for post-hoc justification.

As legality gives way to capability, states hedge more aggressively, faith in a rules-based order weakens, and incentives grow for self-help strategies, including military build-up and potential proliferation.

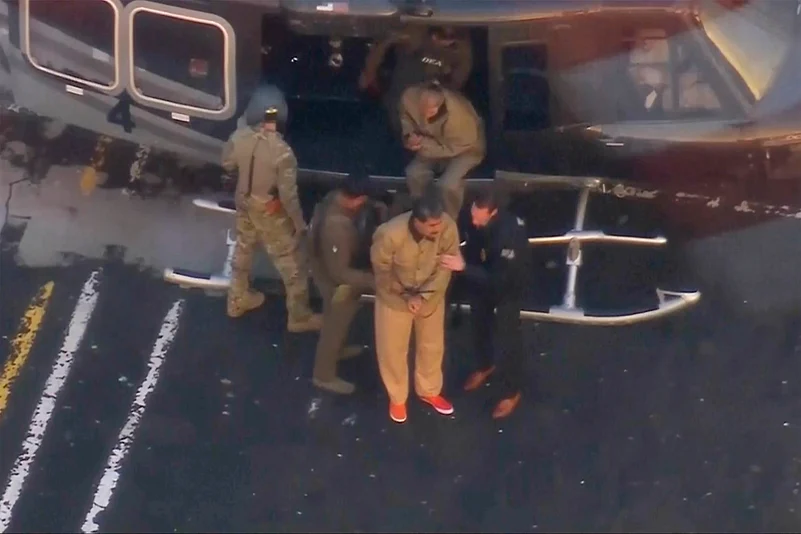

The U.S. raid on Caracas and the capture of Nicolás Maduro will be remembered less for its operational audacity than for what it quietly exposed. It showed how narrow the space has become in which international power still feels obliged to speak the language of law. Hypocrisy has always been part of international politics. What feels different today is that it no longer bothers to disguise itself as principle. The Caracas operation did not simply test the limits of sovereignty; it suggested that those limits may no longer matter when power is sufficiently concentrated and the target sufficiently isolated.

For much of the post–Cold War period, global order rested on a broadly shared assumption: that American primacy, however self-interested, underwrote stability; that institutions could restrain excess; and that sovereignty, though unevenly applied, retained some residual meaning. That assumption was never universally accepted, but it nonetheless shaped diplomatic practice. Caracas has strained it. Operation Absolute Resolve was neither concealed nor plausibly deniable. It was carried out openly and defended as enforcement rather than violation. The message was unmistakable: a permanent member of the Security Council can remove a sitting head of state and frame the act as necessity. Whether one approves of Maduro is beside the point. The precedent matters more than the personality.

What marks this moment is not violence alone, but its routinisation. Coercion increasingly appears not as an exception to international order, but as one of its accepted instruments. Caracas cannot be treated as an isolated episode. It belongs to a broader pattern. The war in Ukraine has normalised territorial revision by force, later justified through historical or security claims. Israel’s expanding strike geography has blurred the line between deterrence and habitual escalation. China’s military signalling around Taiwan now resembles preparation as much as posturing. These cases differ in context and legality, but they converge in effect. They point to a steady erosion of restraint on the use of force by powerful states, particularly when the costs appear manageable and the consequences diffuse.

Understanding this shift requires stepping back from moral denunciation, which has limited explanatory value. A more sober approach looks at how systemic pressures are translated into policy. Three forces appear especially relevant. First, the strategic environment has hardened. Relative power is contested, technological rivalry has intensified, and spheres of influence have returned as an unembarrassed part of elite vocabulary. In such conditions, restraint is often reinterpreted as vulnerability.

Second, domestic politics matters. Leaders operate within electoral and media ecosystems that reward visible resolve. Acts of coercion can be framed as decisiveness, while restraint is easily recast as weakness. In these settings, legality becomes secondary to optics. Third, the tools of intervention have changed. Precision strikes, surveillance dominance, and cyber capabilities reduce the perceived risks of escalation. Operations that appear swift and controllable encourage the belief that force can be applied surgically, without long-term consequence. That belief is often misplaced, but it remains politically attractive. These dynamics help explain why actions once considered unthinkable are now defended as pragmatic.

The United Nations responded in familiar ways. Emergency sessions were held on 3 and 6 January 2026. Statements were issued. Draft resolutions were circulated, nothing concrete came out. Those sessions looked like the concert of great powers. None of this should surprise us. The deeper issue is structural. The post-1945 settlement assumed that great powers would, at minimum, share an interest in preventing the system from collapsing into unchecked coercion. That assumption no longer holds ground.

More troubling is the shift in how the institution is used. The UN increasingly serves as a stage for justification rather than a site of restraint. When enforcement is selective and sovereignty conditional, law risks becoming less a constraint on power than one of its rhetorical resources. This does not mean the UN is irrelevant. It does mean that its protective capacity is uneven and that unevenness is now widely understood.

From New Delhi, this transformation looks less abstract than it might from elsewhere. India has long defended strategic autonomy as the ability to navigate major-power rivalry without subordination. But autonomy is harder to sustain when sovereignty itself appears negotiable. The Caracas precedent complicates India’s diplomatic balancing. New Delhi seeks closer ties with Washington while positioning itself as a representative voice of the Global South. That posture becomes fragile when norms appear pliable and enforcement discretionary.

The uncomfortable question follows naturally: if international law no longer functions as a reliable shield, what does security rest upon? For a state that depends on stability to sustain growth and manage regional pressures, this is not a theoretical concern. The language of a rules-based order increasingly sounds aspirational rather than descriptive. Its selective application invites scepticism, particularly among middle powers asked to invest in norms they cannot rely upon equally.

One consequence of such actions is the way precedent travels. Arguments once dismissed as cynical gain new traction. Russia’s claim that Western violations hollowed out sovereignty norms has long been contested. Caracas does not validate that argument entirely, but it strengthens its rhetorical appeal. Visible impunity encourages imitation. When coercive acts are absorbed without decisive cost, they recalibrate expectations across regions. What was once exceptional begins to look permissible.

There is also a more destabilising implication. States observing these developments will draw their own conclusions. Ukraine relinquished nuclear weapons and received assurances; it was later invaded. Venezuela lacked a nuclear deterrent; its leadership was seized. North Korea, by contrast, remains largely insulated. This comparison is uncomfortable, but it is not easily dismissed. It suggests that sovereignty is increasingly protected by capability rather than law. That lesson, if internalised, has consequences for proliferation dynamics. Insecurity, not ideology, is the usual driver. This may overstate the inevitability of proliferation. But the incentive structure is shifting, and that alone warrants attention.

It would also be naïve to ignore material interests. Venezuela’s energy resources sit uncomfortably close to the surface of any strategic analysis. Great powers rarely frame interventions in economic terms, preferring the language of order or stability. Yet history suggests that material considerations never disappear; they are merely rebranded. When coercion is described as enforcement and extraction as stabilisation, familiar patterns reemerge in updated form. The effect is to reinforce long-standing critiques of global order as hierarchical rather than rule bound.

What emerges from Caracas is not a sudden collapse of international order, but a sharpening of its contradictions. Precedent is beginning to outweigh principle. Capability increasingly substitutes for legitimacy. Middle powers hedge more aggressively, and faith in institutions weakens. This does not mean the world has “returned” to some pre-modern condition. It suggests instead that the restraints we assumed were solid were always more fragile than advertised. The danger lies less in any single action than in accumulation. Each violation that passes without consequence lowers the threshold for the next. Over time, that becomes a form of common sense—and common sense, once established, is difficult to reverse.

Dr Zahoor Ahmad Mir is an Assistant Professor of Political Science. He writes on geopolitics, security, International Relations. He can be mailed at: mirzahoor81.m@gmail.com

Dr Firdoos Ahmad Reshi is an Assistant Professor of Political Science. He can be mailed at reshidous88@gmail.com