The 2025 Nobel Peace Prize highlighted how moral symbols can overshadow political realities, elevating figures like María Corina Machado without guaranteeing democratic progress.

Rather than reinforcing democratic legitimacy, the Prize shifted global attention from Maduro’s authoritarianism to Trump’s interventionist manoeuvres.

The episode reflects a historical pattern in which the Nobel Peace Prize risks rewarding spectacle over genuine, long-term contributions to peace.

In an already complex geopolitical landscape, the awarding of the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize has proved a pivotal yet deeply contentious development, acting less as a marker of democratic legitimacy than as a trigger for unintended consequences. In hindsight, the award constitutes a paradigmatic instance of what amounts to an ethical failure. In other words, it stands out as a symbolic gesture whose consequences have precipitated María Corina Machado's political eclipse shifted global attention from Nicolás Maduro's authoritarian dispensation to the vicissitudes of Donald Trump's interventionist gambit.

Within the logic of international acclaim, symbols often carry more weight than institutions or individuals. For much of the past decade, Venezuela’s crisis was framed as a clear moral binary: Nicolás Maduro as the authoritarian ruler, and María Corina Machado as the resolute face of democratic resistance. Events between late 2025 and early 2026, however, laid bare the fragility of this narrative. The Nobel Peace Prize, arguably the most compelling symbol of international moral commendation, did not initiate a democratic transition. Instead, it hastened a reversal that repositioned Donald Trump, rather than Maduro, as the central agent/rogue of political destabilization in Venezuela.

When the Nobel Committee announced in October 2025 that Machado would receive the Peace Prize for her “civilian courage,” the decision appeared to uphold the moral authority of Venezuela’s opposition. Maduro remained in power, and Machado embodied a politics ostensibly grounded in nonviolence and democratic tenacity. This was apparently the message that went across the world. Yet the award was issued amid a profound contradiction. While the Committee celebrated Machado’s commitment to peace, she was simultaneously aligning herself with a political actor whose polarising legacy and grandiloquence were deeply incompatible with the very values the Prize claims to honour. By the time she accepted the award, it had become evident that her reliance on Trump was not tactical but a guiding principle of her ambition and political strategy.

The irony of the 2025 Prize lay not only in its award but in its reception. Machado dedicated it to Trump, praising his “vision” and his claimed role in ending global conflicts. What appeared to be a gesture of gratitude was in fact an uneasy attempt to align the Nobel’s liberal-democratic symbolism with Trump’s belligerent, strong-arm foreign policy. The attempt failed. As American naval deployments stepped up in the Caribbean and “Operation Absolute Resolve” entered public discourse, Machado’s image as a Nobel laureate became inseparable from the optics of U.S. intervention. While Maduro remained the figurehead of past repression, Trump increasingly appeared as the architect of Venezuela’s political future.

The deeper political cost of the Prize, however, emerged not in Caracas but in Washington. Reports from within the White House in early 2026 suggest that Trump, who had long coveted the Nobel Peace Prize for himself, interpreted Machado’s award as a personal affront. What had been framed publicly as a shared victory for “freedom” was privately recast as an act of symbolic displacement. According to insiders, Machado’s refusal, or inability, to deflect the honour towards Trump irreversibly diminished her political and moral standing. The Prize that was meant to render her politically sacrosanct instead rendered her dispensable.

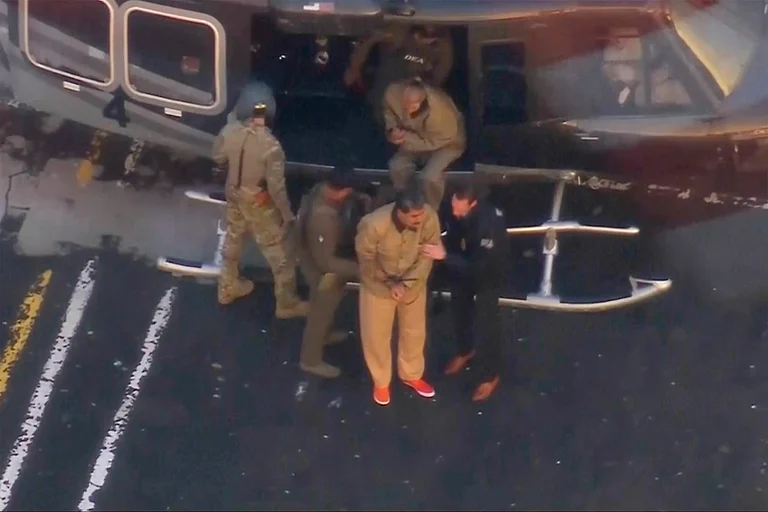

Understandably, with the capture of Maduro, the collapse of the old regime left a vacuum only to be filled by Trump with minimal delay. His statements declaring that the United States would “run” Venezuela and reorganise its oil sector to American advantage drove out any remaining illusion that Machado’s Nobel recognition implied a triumph of Venezuelan sovereignty. The fall of an authoritarian ruler was quickly overshadowed by the spectacle of a foreign power treating a nation-state as an operational asset. Machado stood sidelined, replaced by figures from the ancient régime, most notably Delcy Rodríguez, who proved more acquiescent to the emerging logic of external control.

This sequence of events underscores a more profound disenchantment with the symbolic politics of international recognition. The Nobel Peace Prize, long seen as a symbol of moral authority, came to illustrate a strategic misjudgement. It exposed that Machado’s rise relied on the hope of an external saviour whose priorities were less about democratic renewal and more about resource gain and diplomatic spectacle. Her later public offers to “share” or even hand over the Prize to Trump marked the final phase of this reversal, reducing the laureate from a figure of defiance to one of deference.

In public perception, the focus of culpability has thus shifted decisively. The deposed dictator awaiting judgment has been eclipsed by an interventionist leader who subordinated a nation’s fragile hopes for self-determination to personal ambition and geopolitical transaction. Consequently, the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize will endure not as a testament to peace achieved, but as a lesson in how moral symbols can be leveraged, and sacrificed, once power reveals its true concerns.

The global rush to anoint figures like María Corina Machado as moral icons reveals less about their politics than about the public hunger for uncomplicated heroes. It is well known that in moments of democratic crisis, the Nobel Peace Prize has often functioned as a way for the liberal international order to signal virtue without doing the harder work of scrutiny. Machado’s resistance to authoritarianism is real, but so too is her long-standing alignment with elite interests, external power blocs, and a politics that is as much about expediency and consolidation. Characterising her uncritically as the epitome of democratic hope risks conflating oppositional politics with substantive transformation, and mistaking personal courage for strategic political efficacy

It is here that the Nobel Prize itself appears blemished, not because it recognises dissent, but because it increasingly mistakes posture for principle. When the prize becomes a geopolitical lever rather than ethical judgment, it risks being swayed by carefully staged narratives of resistance to any oppressive regimes. Machado tried to play this game astutely, speaking the language the world wants to hear, while leaving unanswered questions about power, inclusion, and the interests such invocations of democracy serve. The tragedy is not that such figures are fêted, but that the celebration forecloses sustained critical thought. In that moment, the Peace Prize ceases to interrogate power, and instead, silently reinforces it.

Understandably, the unease surrounding the possible elevation of María Corina Machado to the status of a Nobel laureate is not without precedent. The Nobel Peace Prize has repeatedly demonstrated a structural blind spot, a propensity to reward symbolic forces of opposition or diplomatic posturing before the long-term political consequences of power come out in the open. History offers sobering reminders - of Henry Kissinger’s 1973 award, granted while the Vietnam War and the bombing of Cambodia continued. It was a clear indication of how the Committee could mistake elite negotiation and political theatrics for peace itself. For instance, Aung San Suu Kyi’s canonisation in 1991, followed by her later complicity in the Rohingya genocide, revealed the distance between moral elevation and political reality. Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed’s 2019 prize similarly conflated a single diplomatic breakthrough with an enduring commitment to peace, even as his country descended into devastating internal conflict. Even Barack Obama’s early award in 2009 recognised promise rather than achievement, privileging rhetoric over results.

These are not aberrations but instances of a recurring pattern in which the Peace Prize functions less as ethical judgment than as geopolitical endorsement. It is precisely this pattern that should caution us against uncritical celebration of Machado. To repeat, opposition to authoritarianism, however courageous, is not synonymous with democratic transformation. When the Nobel Committee rewards figures whose politics remain deeply entangled with elite interests, external alignments, and unresolved ambitions for power, it risks repeating its own history of haste and misplaced honour. Read in this light, Machado’s elevation as a global democratic icon echoes the Nobel’s familiar errors of the past.