In 2024, a student-led revolution toppled Sheikh Hasina’s government in Bangladesh, leading to widespread anarchy.

The 2024 uprising, marked by both hope and violence, underscored deep-seated frustrations in Bangladesh, with widespread protests, casualties, revealing an urgent need for institutional reforms.

As Bangladesh prepares for general elections in February 2026, the National Citizen Party (NCP) has raised concerns over the impartiality of the Election Commission.

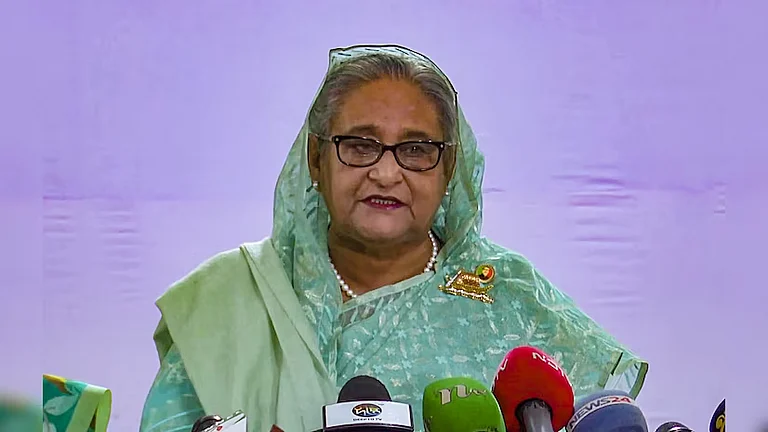

A student revolution toppled Sheikh Hasina’s government in 2024 in a bid to establish a more equitable and less corrupt democracy. As Hasina fled to India, she left behind a nation on the brink of collapse, where anarchy ran rampant. Following her departure, Nobel Peace Prize-winning economist Muhammad Yunus was installed to guide the country from chaos toward stability.

However, the Yunus government has struggled to curb violence against minority communities. His attempt to appoint 11 commissions tasked with proposing reforms—including changes to the electoral system, judiciary, and police—has yielded little impact.

After two tumultuous years, a democratic glimmer now lurks around the corner. General elections are expected to take place in Bangladesh in February 2026.

Amid preparations for these elections, the National Citizen Party (NCP) has raised serious concerns about the impartiality of the Election Commission of Bangladesh (EC), calling for the entire body to be reconstituted before the polls. During a meeting with Muhammad Yunus, Chief Adviser of the interim government, NCP convener Nahid Islam alleged that the formation and current functioning of the EC lacked transparency and independence. “A neutral Election Commission is essential for a fair election,” he asserted, adding that the commission’s credibility has already been compromised.

In addition to calls for restructuring the EC, the NCP demanded a clear timeline for justice pertaining to the families of martyrs and the injured in the July 2024 uprising, warning that without broader institutional reform, the electoral process would not be credible.

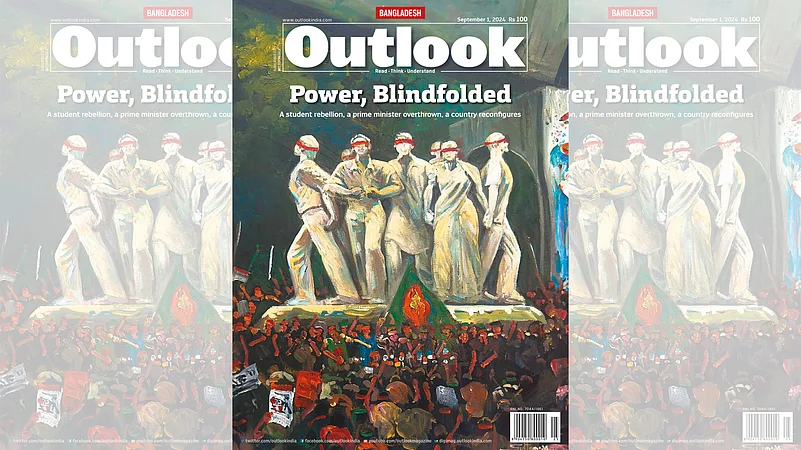

In Outlook’s September 1, 2024 issue, ‘Power, Blindfolded,’ we reported how the protests in Bangladesh were about more than just toppling a regime. In ‘Behind Bangladesh Protests: The Weight of Deep-Seated Frustrations,’ Rabiul Alam recalled the night when revolution struck. The atmosphere was electric, charged with both hope and fear. As the crowd surged forward, their voices rose higher, challenging the regime. Then, a sharp crack pierced the evening air—a bullet fired into the throng. The world seemed to slow down as Shazid was struck. The bullet entered the back of his head, tore through his brain, and exited through his eye. In an instant, the energy of the protest shifted from defiance to panic. Shazid crumpled to the ground, his blood mingling with the dust, as his life ebbed away and fellow protesters looked on in horror.

The turning point came when news spread that Sheikh Hasina had fled the country. The atmosphere in Dhaka shifted from tension and fear to overwhelming jubilation.

The jubilation, however, turned immediately into dread for a few. Snigdhendhu Bhattacharya highlighted ‘The Hindu Question in Bangladesh.’ In an interview with Rana Dasgupta, the General Secretary of the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council, he shed light on how the main targets during the communal attacks were the houses, businesses, and places of worship, mostly of Hindus. The attacks included loot, vandalism, and arson. There were also a few cases of molestation. We have sent an account of such incidents to the chief advisor via an open letter.

Shahinur Sumi wrote on ‘What the Women in Bangladesh Fought For.’ In this struggle, female students and women played a vital role. Mothers joined the protests to stand by their children not only in Dhaka and other cities but also in villages across every district. On several occasions, the presence of women in large numbers prevented the police from opening fire. The number of casualties would have been much higher had women not taken to the streets in such large numbers. Female students were involved in all forms of agitation.

Seema Guha highlighted India’s challenge to break with the past and begin afresh with the new power centre in Dhaka. She mentioned the multiple tests ahead for India’s ‘strategic patience’ on Bangladesh. New Delhi’s inability to anticipate the tumultuous events that led to the ouster of Hasina or realize the strength of the student movement is a sad reflection not only of our diplomacy but also of India’s intelligence agencies, which failed to gauge the mood on the streets. India was perhaps complacent, believing that Hasina could crack the whip and keep things under control as she had done in the past.

With a new power centre taking shape, the Bangladesh elections will be a focal point for all of South Asia.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)