When the Trinamool Congress (TMC) first came to power in West Bengal in 2011, says a hooch seller, he had to close down his business for a few months. It was not because Mamata Banerjee’s TMC was running any anti-alcoholism campaign. His illegal shop was located near the boundary of two police stations. The seller, a voter of the Chinsurah assembly segment within the Hooghly Lok Sabha seat in southern West Bengal, says that during the Left Front government rule, cops from only one police station used to reportedly ask for their “monthly payment”. But after the TMC came to power, he allegedly faced payment demands from not only the other police station, but also from three local TMC leaders.

He got arrested, allegedly for refusing to pay up. On being released, he resumed his business only after settling the “payments” of these people. He alleges that prices of hooch and marijuana—both illegal items—shot up during the beginning of the TMC rule as “protection money” to the police and politicians increased with time.

But it is not just these contraband items that became costlier. Land, real estate and local businesses, dealers in all these sectors allegedly had to account for a “cut” or “cuts” for the local TMC leaders and “syndicates”.

‘Syndicate’ refers to extortion rackets involving unemployed youth that force people—whether realtors building apartments or individuals building a home for their family—to procure construction material from them at unreasonable rates.

The TMC sensed the trouble growing soon after coming to power. In August 2014, Jyotipriya Mallick, the TMC’s North 24 Parganas district unit president and influential minister, issued a circular to party workers and leaders in the district, forbidding them from being “involved directly or indirectly with brick kilns, fisheries, syndicates and land dealings”. This circular came following repeated verbal warnings from Banerjee. But as the people of the state have experienced, the practice continues unabated.

“The CPI (M) used to steal fish from the pond. The TMC steals the pond itself,” says Ujjwal Ghosh, a real estate broker in Bangihati that falls under the Serampore Lok Sabha constituency. In many parts of the state, disputes over the share of such unaccounted money earned through illegal or coercive means lead to inner-party rivalry and violence, often resulting in leaders of one faction of the TMC being accused in the murder of a leader of another faction of the party.

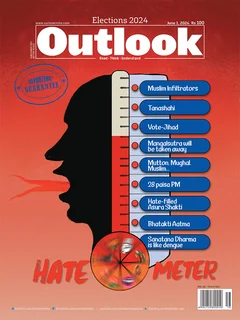

However, the TMC’s new challenger, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), offers Ghosh no hope. He says the Hindu nationalists divert public attention from the real issues with their communal rhetoric. As Ghosh speaks, a BJP rally passes by. Chants of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ rent the air. A loudspeaker blares out a song from the genre that has become known as ‘Hindutva pop’—disco music with toxic, anti-Muslim lyrics. In 2011, Communist, nationalist and patriotic songs were played at election rallies. But religion is now a part of the political mainstream.

In 2006, in the wake of the anti-displacement movements in Singur and Nandigram, the TMC dumped its ally, the BJP, to join hands with smaller Left parties to unseat the CPI (M)-led Left Front government. During the same period, retired Justice Rajinder Sachar-led committee’s report deeply impacted Bengal’s political culture, as it revealed the socio-economic backwardness of Muslims in West Bengal.

As the TMC took on the issue of Muslim backwardness, Muslim religious leaders and clerics such as Siddiqullah Chowdhury, state unit president of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind and Noor ur Rahman Barkati, imam of Kolkata’s Tipu Sultan mosque started appearing on the TMC’s rallies, calling for a change in government. This marked the beginning of religion entering the mainstream of West Bengal politics.

Though the CPI (M) contested the Sachar Committee findings, it accepted the Ranganath Misra Commission’s 2009 recommendations of including some more backward Muslim communities under the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category—increasing the Muslim OBC reservation share from seven per cent to 17 per cent.

Citing the presence of Muslim religious leaders on the TMC’s dais and the CPI (M)’s Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee government’s decision to increase Muslim OBC reservation, the BJP and the Sangh Parivar started building their base. By the time Narendra Modi emerged at the national level in 2013 with his Hindu nationalist agenda, the ground was set in West Bengal for a campaign against corruption and ‘minority appeasement’. In another five years, the BJP overtook the Left as the TMC’s principal challenger.

About the major changes in the state’s political culture, Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury, a political scientist at Rabindra Bharati University in Kolkata, mentions the increase in personal attacks during political campaigns, the lack of ideological fight and an increase in the extent and scale of corruption. “Earlier, the ideological battle between the Left and the Congress dominated the state’s politics and electoral campaigns. That is no longer there,” says Basu Ray Chaudhury. He adds that in the era of neoliberal economy and populist politics, even the Communist parties are Communist only in name, and not in practice.

“Communist parties have little difference from the populist parties now. As the TMC has earned the confidence of the downtrodden through welfare schemes, the ideological battle has receded into the background,” he says.

He points out that personal attacks in political campaigns largely remained under control during the Congress rule and the three decades of Left Front rule that followed. However, from the time of the Singur-Nandigram agitations, the CPI (M) leaders started losing control over their language. This new language of personal attacks became the new normal for Bengal.

He, though, does not blame the TMC alone for the increase in the extent and scale of corruption. “We discuss the corruption of the babus and the netas, but corruption has actually increased in all sections of the society as an impact of the neoliberal economy that puts money at the centre of everything,” he says.

While corruption under the TMC rule has shocked and disgusted a section of the electorate, there also are many who do not care. “The TMC people steal more but also work more,” says a homemaker in Chinsurah town, part of the Hooghly Lok Sabha constituency. She points out that the municipal corporator in their ward used to be a “real gentleman”, but the new TMC corporator is “an illiterate to the core”. By illiterate, she does not mean lack of degrees, but lack of “basic education”. Yet, she concedes that the TMC corporator has done more work. “Everybody knows his only intention of being in politics is to make money, but we can also see that the amenities improved after he took charge,” she says.

Whether Bengal’s political culture will undergo further changes, and in which direction, depends a lot on how the Left-Congress candidates perform in the elections.

A Lokniti-CSDS post-poll survey of the 2021 assembly election found that 23.9 per cent respondents fully agreed with the statement “there is a lot of corruption in the TMC”, 27.3 per cent somewhat agreed, 12.5 per cent somewhat disagreed and 17.4 per cent fully disagreed. Yet, the TMC got 48.5 per cent of the polled votes in the 2021 assembly election. Understandably, some people voted for the TMC despite considering the party corrupt.

Economist Maitreesh Ghatak wrote in a 2021 article, “Despite the state’s lack of economic dynamism, the rate of growth of purchasing power in rural areas of West Bengal has been higher than the national average during the TMC rule.” As visits to different parts of Serampore, Hooghly and Howrah Lok Sabha seats reveal, many of Banerjee’s welfare schemes enjoy popularity.

According to Udayan Bandyopadhyay, a political scientist at Bangabasi College in Kolkata, major changes in Bengal’s political culture include the waning relevance of “negativist politics like bandhs” and change in the nature of political violence.

“During the Left rule, there were prolonged political turf wars throughout the year. Mass lynching on Kolkata’s Bijon Setu and large-scale killings in Birbhum’s Nanoor and West Midnapore’s Chhoto Angaria shocked and silenced opponents. Now political violence comes to the fore only during election time, mainly the panchayat election,” says Bandyopadhyay.

At the same time, the flow of illegal money in politics, which was under control during the Left rule, has become part of the political mainstream during the TMC rule.

“Now, people need to spend money to get every work done. At every step, someone is asking for commissions. Extortion and syndicate rackets were sporadic in the past, but have now become very powerful, all over the state,” says Bandyopadhyay.

While the BJP hopes to unsettle the TMC by blending an anti-corruption campaign with Hindutva sentiments, there is a new churning, at least in some pockets, with a section of the people getting disappointed with both the TMC and the BJP and looking for a third alternative. The Left’s fresh faces like the Jadavpur candidate, Srijan Bhattacharya, and the Serampore candidate Dipsita Dhar, who are in their 30s, have drawn significant public attention with their oratory skills.

According to data compiled by political analyst Spandan Roy Basunia, of the state’s 42 Lok Sabha seats, the combined votes of the Left and the Congress in the 2023 panchayat election stood higher than the BJP’s in Birbhum, Asansol, Bardhaman-Durgapur, Bardhaman Purba, Serampore, Jadavpur, Diamond Harbour, Basirhat, Barasat, Dumdum, Krishnanagar, Baharampur, Jangipur, Murshidabad, Malda Dakshin, Malda Uttar and Raiganj Lok Sabha seats.

Of these, the combined vote share of the Left and the Congress was above 20 per cent in Birbhum, Bardhaman-Durgapur, Bardhaman Purba, Hooghly, Sreerampur, Jadavpur, Barasat, Barrackpore, Krishnanagar, Baharampur, Jangipur, Murshidabad, Malda Dakshin, Malda Uttar and Raiganj. In Bankura, Purulia, though the BJP was ahead of the Left-Congress combined votes, the latter’s share was above 20 per cent.

Whether Bengal’s political culture will undergo further changes, and in which direction, depends a lot on how the Left-Congress candidates perform in the elections. The BJP failed to maintain its 2019 momentum in 2021. If the Left shows any signs of recovery, the plot might be in for a twist.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya in Kolkata

(This appeared in the print as 'Shine Off Sonar Bangla')